About three-quarters of a mile below Assisi stands the little convent of San Damiano. Built on a hillside, on an elevation from which the whole plain may be viewed through a curtain of cypresses, it has become the residence of the Friars Minor after having been that of the Poor Ladies.

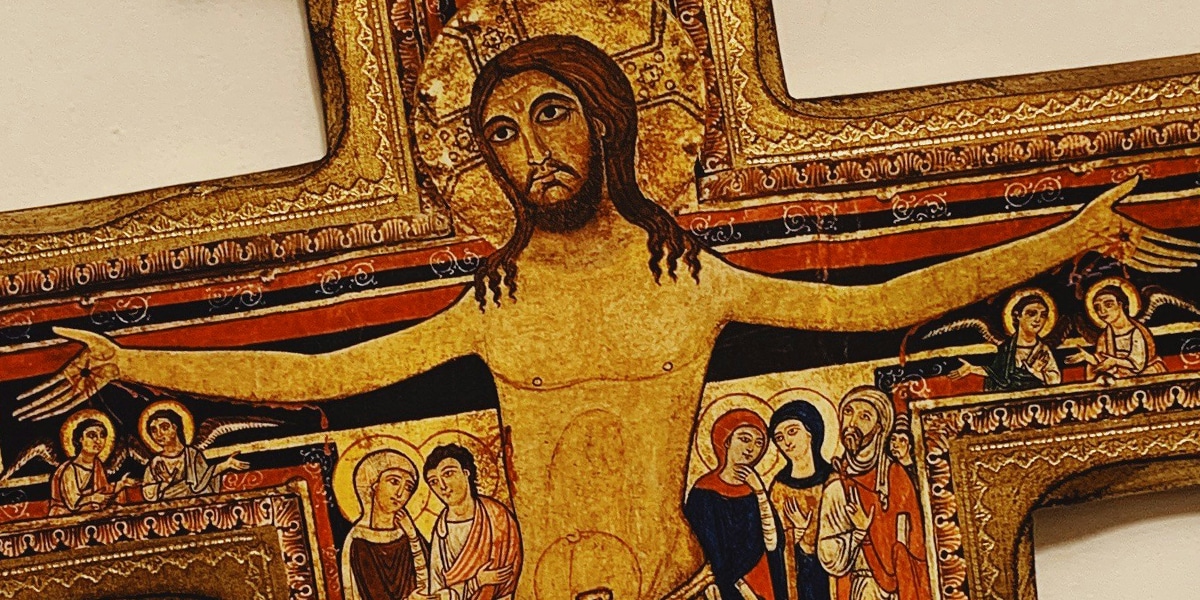

But in the spring of 1206, all that was there among the wheat fields sparsely set with olive trees was a ruinous chapel. Within, suspended over the altar, hung a mild and serene Byzantine crucifix. Although the church was no longer frequented, an indigent priest was still attached to it, living, no doubt, on alms and the suffrages of the faithful.

“Now one day as Francis was passing, he entered the chapel. Kneeling before the wooden crucifix, he began to pray, when suddenly the figure of Christ, parting its painted lips, called him by name and said, ‘Francis, go repair My house, which is falling in ruins;’

“It would be impossible,” the biographer continues, “to describe the miraculous effect that these words produced on the hearer, since the latter declared himself incapable of expressing it. But one may reverently conjecture that Christ then impressed on his heart the sacred wounds with which he was later to mark his stigmatized body.

For how many times in the future was not the blessed man to be met along the road, shedding compassionate tears over the Savior’s Passion?”

It was not a rare thing for knights to become builders of churches, in expiation of the faults committed in their adventure-filled lives. Had not one of the four sons of Aymon, men said, abandoned his military career to help build the Cathedral of Cologne? Francis may have believed himself called on to imitate him; for, taking literally an order evidently applying to the Church of Christ itself, he at first thought that he was to restore the chapel of San Damiano. He at once offered the priest money for oil and a lamp, so that a suitable light might burn before the image of Christ crucified.

But where was he to find the necessary resources for rebuilding the chapel?

That need not be an obstacle! Francis thought of his horse and the bales of cloth at home. He returned home, made up a bundle of the most precious stuffs, then fortifying himself with the sign of the cross, leaped to the saddle and set off at a gallop for Foligno. There (as he usually did) he met customers who bought his merchandise.

He also sold them his horse, so that he had to make the ten miles back to Assisi on foot. When he returned, the priest of San Damiano was in the chapel. Francis kissed his hands, detailed his plans to him, and attempted to give him the receipts for his sale. But the priest took this at first for a practical joke. Was not this risky money, which might embroil him with Francis’s family? And then, how was a man to believe in the sudden conversion of this young fop, who even yesterday was scandalizing the whole town by his follies? So, Francis did not succeed in having his gift accepted. But he did win the priest’s confidence and got his permission to stay with him. As for the purse that was burning his fingers, he tossed it like a dead weight into the corner of a window and thought no more about it.

Meanwhile, Peter Bernardone was in a towering rage and deeply distressed at learning what his son had done. Assembling his friends and neighbors, he rushed to San Damiano “to seize the fugitive and bring him home.”

Fortunately, the new hermit had taken care to secure a place of refuge—a sort of dugout under a house that no one, except a friend, knew about. As the conspirators drew near, he ran and hid in it, and let them shout it out. He hid for a whole month, eating in his cave the little food that was brought him, and beseeching God to help him carry out his plans. And in this dark retreat, the Lord sent him such consolation and delight as he had never known.

The time came, however, when, blushing at his fears, he left the hiding place; and resolved to face the music, he headed for town. He was exhausted by his austerities. People seeing him gaunt and wan—he who a short time before had been so full of life—thought that he had lost his mind, and began to yell, “Lunatic! Madman!” Urchins slung stones and mud at him; but he went on, without appearing to notice their taunts.

Hearing the hullabaloo, Peter Bernardone came out of the house and saw that it was his son they were harrying. He became furious. Hurling himself on Francis like a fierce wolf on an innocent lamb, he dragged him into the house, where he chained him and shoved him into a dungeon. He spared neither arguments nor blows to wear down the rebel, but the latter refused to be shaken.

Personal business, however, obliged the father to leave; and Francis’s mother profited by this to try her hand at swaying her son.

Seeing that he remained inflexible, one day when she was alone in the house, she broke his chains and set him free. The father’s fury knew no bounds, when, on his return, he learned of the prisoner’s escape. He launched into reproaches against his wife; then attempted a final move at San Damiano, where Francis had again settled.

But trial had steeled his courage. He went forth now with assurance, with peaceful heart and joyous mien. He calmly walked up to his father, declaring that he no longer feared either irons or blows and that he was ready to endure all things for the love of Christ. Feeling that all hope was lost for the time being, Peter Bernardone concerned himself only with recovering the Foligno sales money and sending the young rebel into exile. This respectable citizen hoped in this way to get the son who shamed him out of the way, and perhaps by cutting off his living, to bring him back home someday.

Shouting angrily on the way, he rushed to the palace of the commune, and swore out a warrant before the consuls. The magistrates charged a town crier to summon Francis to appear before them.

But the young man, who was bothered neither about exile nor about giving back the money, refused to obey; and claiming that having gone into God’s service, he was no longer under civil jurisdiction, he declined to appear. The consuls declared themselves incompetent and rejected the plaintiff’s claim, leaving him with no recourse but to appeal to the jurisdiction of the Church.

The Bishop of Assisi at that time was Lord Guido, who occupied his diocese until after the saint’s death. He formally bade the accused to appear before his tribunal. “I will go before the bishop,” replied Francis, “for he is the father and master of souls.” The judgment was most probably rendered in public, in the piazza of Santa Maria Maggiore, in front of the bishop’s palace.

“Put your trust in God,” said the bishop to the accused, “and show yourself courageous. However, if you would serve the Church, you have no right, under color of good works, to keep money obtained in this way. So give back such wrongly acquired goods to your father, to appease him.”

“Gladly, my Lord,” replied Francis, “and I will do still more.” He went within the palace and disrobed; then, with his clothing in his hands, he reappeared, almost entirely nude, before the crowd.

“Listen to me, everybody!” he cried. “Up to now, I have called Peter Bernardone my father! But now that I purpose to serve God, I give him back not only this money that he wants so much, but all the clothes I have from him!” With this, Francis threw everything on the ground. “From now on,” he added, “I can advance naked before the Lord, saying in truth no longer: my father, Peter Bernardone, but: our Father who art in Heaven!”

At this dramatic climax the bishop drew Francis within his arms, enveloping him in the folds of his mantle. The spectators, catching sight of the hair shirt that the young man wore on his skin, were dumbfounded, and many of them wept. As for Peter Bernardone, unhappy and angry, he hurriedly withdrew, taking with him the clothing and purse.

And that was the way Francis took leave of his family. One would like to think that he saw his mother again, and from time to time showed some mark of tenderness toward this woman who admired him and had had an intuition of his sublime destiny.

But the biographers make no further mention of her. For some time after that, Francis did no more about San Damiano. The funds on which he had counted had vanished, and he had not yet learned that poverty sufficeth for all things. He had first to go in search of suitable clothing, since all that he had to cover him was a little coat full of holes that the bishop’s gardener had given him after the scene of the day before. He drew a cross on it with chalk by way of a coat of arms; then he set out through the woods singing the Lord’s praises in French at the top of his lungs.

His heart was overflowing with joy. There was to be no more now of circumspection and feeling his way. A pathway of light opened straight before him. He was consecrated to the Master’s service; he had just been made Christ’s knight and had solemnly espoused Lady Poverty. God was rewarding him by making him happy. He was making the woods ring with his songs when some robbers, scenting a prey, rushed up.

This man with his threadbare cloak was a disappointment to them. “Who are you?” they asked. “I am the herald of the Great King!” replied Francis with assurance. As he did not yet have the gift of taming wild beasts, the robbers beat him up and threw him into the snow at the foot of a ravine. “There you are, oaf!” they shouted as they made off. “Stay there, God’s herald!”

Francis climbed out of the slush-filled hole only with great effort, and when the ruffians were out of sight and hearing, he went on his way, singing louder than ever. He then directed his footsteps to a monastery, where he thought the monks would consent to clothe him in exchange for work.

The monks took him on as a kitchen helper but gave him nary a stitch to cover him. For food, they let him skim off a little of the greasy water they fed the pigs. It is true that afterward, when Francis’s reputation for sanctity began to be established, the prior was ashamed at the way he had treated him and came to beg his forgiveness. And he obtained it easily, for the saint said that he had very pleasant memories of the few days spent in his kitchen.

It was at Gubbio that an old friend gave him something to wear. So afterward men saw him wearing a hermit’s garb—a tunic secured at the waist by a leather belt, sandals on his feet, and a staff in his hand. He next stayed a while with the lepers, living in their midst, bathing their sores, sponging off the pus from their ulcers, and giving them loving care for the love of God.

Then he went back to San Damiano.

There, the chaplain still recalled recent events, and Francis had to reassure him by telling him of the bishop’s encouragement and approval. After this, the restoration of the chapel could begin. As Francis had no money with which to buy materials, he was obliged to beg for them. He went through the city crying, “Whoever gives me a stone will receive a reward from the Lord! Whoever gives me two will have two rewards! Whoever gives me three will receive three rewards!” Sometimes, like a jongleur who sings in order to earn his salary and repay his benefactors, the collector would interrupt his rounds to sing to the glory of the Most High.

And whether he addressed himself to God or to men, whether he begged for hewn stone or celebrated the divine attributes, the Little Poor Man (his biographers observe) “always spoke in a familiar style, without having recourse to the learned and bombastic words of human wisdom.” Is this an allusion to the jargon and to the false science that flourished in the schools? One thing certain is that here you have defined the man and the style, which go together in St. Francis.

Simple he was in his person, having but one aim and one object, honestly and openly sought. Simple he was in speech, knowing what he said, and saying only what he knew; avoiding lengthy, pompous, and obscure discourse, speaking—like Jesus in the Gospels—to make himself understood and to be useful to others. Picturesque and sublime, his talks, coming from the heart, reached men’s hearts, delivering them from their sadness and their sins, and revealing to them the happiness that comes from belonging to God.

Moreover, if many still held the new hermit to be a madman and persisted in insulting him, many already were beginning to understand him; and, moved to the depths of their being, they wept as they listened to his words. They saw him carrying stones on his back and striving to interest everyone in his project. Standing on his scaffolding, he would joyously hail the passersby. “Come here a while, too,” he would shout, “and help me rebuild San Damiano!”

It may be that crews of masons responded to his appeals, and working under his direction, helped him in his tasks. It was then, accounts tell us, that he predicted that virgins consecrated to God would soon come and take shelter in the shadow of the rebuilt chapel. One can imagine how he drove himself—he who had always been petted and pampered by his parents. Taking pity on him, his priest-companion began—poor as he was—to prepare better food for him than that with which he himself was satisfied.

Francis, at first, raised no objections; but seeing that he was being mollycoddled, he said to himself: “Francis, are you expecting to find a priest everywhere who will baby you? This is not the life of poverty that you have embraced! No! You are going to do as the beggars do! Out of love for Him who willed to be born poor and to live in poverty, who was bound naked to the cross, and who did not even own the tomb men laid Him in, you are going to take a bowl and go begging your bread from door to door!” So Francis went begging through the town, a large bowl in his hands, putting everything that people gave him into it. When it came to eating this mess, he felt nauseated. He managed, however, to get it down, and found it better than the fine food he used to eat at home.

He thereupon thanked God for being able—frail and exhausted as he was—to adjust himself to such a diet; and from then on, he would not let the priest prepare anything special for him. Let no one imagine, however, that he was not sometimes subject to false shame. For instance, one day when oil was needed for the chapel lamp, he went up to a house where a party was in progress, with merrymakers overflowing into the street. Recognizing some old friends and blushing to appear before them as a beggar, he started back. But he soon retraced his steps and accused himself of his cowardice before them all. Then, making his request in French, he set off again with his oil.

Thomas of Celano observes here that “it was always in French that St. Francis expressed himself when he was filled with the Holy Ghost; as if he had foreseen the special cult with which France was to honor him one day,” and wanted to show himself grateful in advance.

No one, though, ever loved his homeland more than he did, or was more beloved by its people. But the veneration of his fellow citizens did not come in a day. A considerable number of them began by mocking him at will, including his brother, Angelo, eager to show himself for once witty at Francis’s expense. This happened very likely in a church, where Francis was praying one wintry morning, shivering with cold beneath his flimsy rags.

Passing near him with a friend, the brother remarked to his companion, “Look! There’s Francis! Ask him if he won’t sell you a penny’s worth of his sweat!” Francis could not help smiling. “It’s not for sale,” he replied gently. “I prefer to keep it for God, who will give me a much better price for it than you.”

The barbed shafts no longer struck home. Only one thing continued to distress him, and that was his father’s attitude toward him. For every time that Peter Bernardone met his son, he became infuriated and cursed him.

A son like Francis could not remain under the spell of a father’s curses. So, to an old beggar named Albert, he made the following offer: “Adopt me as your son, and I will share the alms I receive with you. Only whenever we meet my father and he curses me, you make the sign of the cross over me and give me your blessing.”

The arrangement was to Albert’s advantage, and we may be sure that he had no scruples about giving so many blessings as there were curses to ward off. So, addressing the wrathful merchant, Francis would say to him, “You see that God has found a way to offset your curses, for he has sent me a new father to bless me.”

Evidently Peter Bernardone was sensitive to ridicule and ended by taking things more calmly, for we hear no more of him in the biographies. No doubt, he lived long enough to behold the rising star of the Little Poor Man. And who knows if, on seeing his son honored by important personages, he did not put as much zeal into acknowledging him as he had into denying him?