Father Mamich’s kidney condition was worsening, and he wasn’t sure where to turn next. The answer, as it turns out, was in the pews all along.

Father Joseph Mamich changed a flat tire in the gray winter light. It was 5:40 in the morning, and the priest was on his way to dialysis, a routine he’d kept for week.

“I’d have dialysis in the morning and be back in the office by 11:30,” Father Mamich says. The pastor of St. Joseph parish in Strongsville, Ohio, he shepherded a flock of 2,593 families assisted by three other priests; one was on temporary assignment. Father Mamich persevered in hearing confessions and other priestly duties, even scheduling funerals around his treatments.

“I’m not sure how I did that,” Father Mamich admits today. “I don’t think I ever knew how sick I was.”

Years earlier, Pope John Paul II listed voluntary organ donation among the acts of “everyday heroism” that build a culture of life. Father Mamich’s everyday hero lived among his own parishioners.

An Ongoing Problem

When he was a first grader, doctors had diagnosed the future priest withpediatricnephritis, inflammation of the kidneys. They predicted he would outgrow it. When he was a junior at Padua Franciscan High School, however, a biopsy indicated that he had Berger’s disease, a condition that impairs kidney function. Doctors warned their young patient that he could need dialysis, a transplant, or treatment with prednisone by the time he was 30 or 40 years old.

Life went on. After high school, Mamich entered the seminary. He was ordained a priest of the Diocese of Cleveland in 2006 and served as parochial vicar in two parishes before becoming pastor of St. Joseph in 2011.

Not long after, his kidneys created other health problems. He began suffering from gout in 2012. For a while, his lungs retained fluid. After doctors prescribed prednisone, he gained weight and woke up for several hours each night.

In February 2013, he scratched his leg in the ocean while vacationing. Back home, doctors treated the ensuing infection with antibiotics during a two-day hospital stay.

“It came roaring back a week later,” the priest recalls. Nauseated, feverish, and experiencing rocketing blood pressure, he spent another week in the hospital with a staph infection. Doctors finally opted for emergency surgery to debride the tissue around his knee.

Then, on Palm Sunday 2013, the priest felt light-headed at the conclusion of Mass. He made his way to a chair in the sanctuary, sat down, and promptly passed out. “It was actually a pretty graceful experience,” Father Mamich says. “A 6-foot guy coming down on the [marble] floor would have been bad.”

Although he dismisses it as “not that dramatic,” news of the incident spread throughout his parish. People openly expressed concern for their pastor’s health. “One particular person had me dead and buried,” Father Mamich says.

Help Within the Parish Family

The pastor decided to curtailrumorsby explaining the situation to his parishioners. In a letter tucked into the weekly bulletin, he informed them of his history of kidney disease, and he asked for their prayers.

He offered an update two months later. “For whatever reason, the progression of the disease has sped up and has come to three possibilities,” he wrote. “Transplant, dialysis, or a miracle.”

Meanwhile, the Kidney Transplant Program at the Cleveland Clinic accepted Father Mamichas a potential organ recipient. He was an only child, and his parents were ineligible because of age; he would not find a donor within his family. He expected to wait for as long as six years for a kidney from a deceased donor.

When people heard about this development, several asked how they might become a living donor for him. At Mass one Sunday, the priest stressed that he was not asking anyone to volunteer, but interested individuals could call the Cleveland Clinic’s Kidney Donor Program.

In the pews, Jim Lechko shot his wife a sidelong glance. “I could just feel the wheels turning in his head,” Sue Lechko now says of the man she married 42 years earlier.

For two weeks, Lechko did not discuss the idea with his wife. But the impulse to volunteer to be a donor returned again and again. He knew the importance of organ donation. His high school football coach had received a kidney from another coach years earlier. “It’s really something I believe in,” Lechko says. “I’ve been signed up to be an organ donor since I was 16 years old when I got my driver’s license.”

At dinner one night, Lechko told Sue he wanted to be tested as a possible donor for Father Mamich. “There are thousands of people just in our country who need organ donations, “Lechko told her. “Their own family members aren’t even matches a lot of the time. What is the likelihood that I’m going to be a match? I just want to go and be tested.”

Still in his 50s, Lechko wasn’t too old to be a donor, and so Father Mamich’s transplant coordinator scheduled him for the first step, a blood draw. Lechko was working on an old convent in Cincinnati with his parish’s Mission of Hope when she called him with the results.

“Not perfect, but still a match,” Lechko says. As it happened, his O-negative blood type made him a suitable donor for patients with other blood types. He has donated more than 17 gallons of blood over the years.

“I go every eight weeks because I know it’s so rare,” he says.

No Doubts

Lechko agreed to report to the Cleveland Clinic for a psychological evaluation and two days of extensive medical tests to ensure he was healthy enough to be a donor. He also confirmed that he had his wife’s full support. “I didn’t want to get Father Joe’s hopes up and then at some point say, ‘I can’t do it,'” he remembers.

Sue Lechko worried about putting Jim’s healthy body through unnecessary surgery. But her husband told her the words of John 15:13 kept running through his mind: “No one has greater love than this, to lay down one’s life for one’s friends.” His rock-solid faith in the outcome also soothed her fears.

“I never doubted the decision,” Jim says. “I never got nervous about doing it [the transplant]. I just felt like I was called to do it.”

Soon after he scheduled the medical tests, Lechko saw Father Mamich at the parish picnic and informed him. Because of confidentiality rules, the priest did not know the name of any potential donor until then. He was acquainted with Lechko, who participated in several parish organizations, and they sometimes chatted in the sacristy when Lechko served as lector. But they were not close friends.

The priest introduced Lechko to his parents but told nobody else because Lechko wished to remain anonymous. He didn’t want his decision to be tainted by a need for recognition. “In my daily prayers, I would pray that I was doing it for the right reason,” Lechko says.

During his subsequent psychological evaluation at the Cleveland Clinic, Lechko was asked how he would feel if Father Mamich’s body rejected the donated kidney. “If God wants this to happen, it’s going to happen,” he replied. “If it is rejected, life goes on. I did what I could do.”

At the clinic, Lechko also learned that he would not be responsible for any medical or hospital bills. “Everything was handled through Father Joe’s insurance company,” he says.

Faith, Prayer, Perseverance

A week after the tests, FatherMamich’stransplant coordinator calledLechkowith the news that his blood pressure and cholesterol level were too high for surgery. She advised him to see his primary care physician to correct these problems and then return in three months.

Lechko’sdoctor recommended a Mediterranean diet and aerobic exercise. “SoI ate a whole bunch of food I typically wouldn’t be eating,” Lechko recalls. “Low-fat breads, a lot of tuna and nuts, dates, raisins, oatmeal, turkey. I started running again.” Before long, he was running five miles, five days a week.

“I went back to the doctor two and a half months later, “Lechko says. “I actually lost 27 pounds. My blood pressure came down. My cholesterol level came down.” He was cleared for the transplant.

Meanwhile, a side effect of one of Father Mamich’s medicines had caused bone deterioration. “I ended up having to have my hip replaced because of the prednisone,” Father Mamich says.

Lechko maintained his good health while waiting for Father Mamich to recover. He resisted the culinary temptations of the holidays, and he ran at 5:00 every morning. Whenever snow piled up, he jogged in the plowed streets.

The transplant finally was set for March 10, 2014. The parish planned an intercessory Mass for that evening. In the meantime, the priest’s kidney function worsened. He began dialysis. The surgery was postponed when doctors found fluid around his heart, and so both FatherMamichand his kidney donor attended their special Mass.

“It was a packed house,” Lechko says. “The prayers were palpable.”

In his homily, Father Mamich mentioned the inconvenient “flat tire” earlier that day. He emphasized the necessity of faith, prayer, and perseverance. When he introduced Lechko as his donor, the faithful prayed for both men by name.

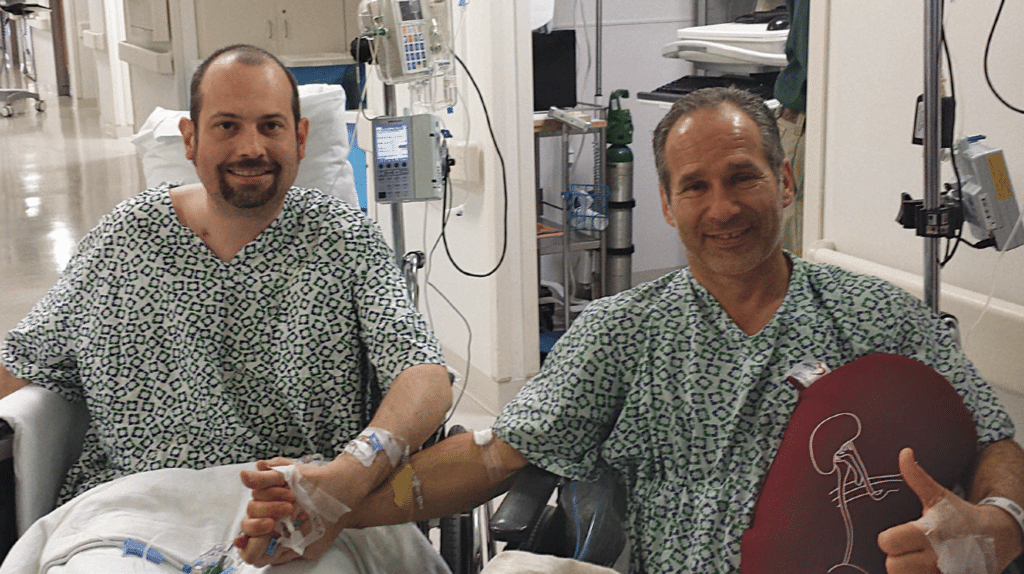

A cardiologist had predicted Father Mamich’s heart condition would not clear up before June, but the fluid inexplicably disappeared within two and a half weeks. The transplant was rescheduled for April 28, 2014. Pastor and parishioner rode to the surgery center together. Neither felt apprehensive. When the two awoke hours later, each learned that the other was well, and that the transplanted kidney was functioning.

Within a couple of days, Lechko’s wife maneuvered him in a wheelchair to visit Father Mamich in another hospital wing. The priest already felt remarkably better. “I wanted out of that bed!” Father Mamich recalls. “I wanted to get going.”

Lechko returned to work after four weeks, but Father Mamich had to avoid crowds for three months. “After the transplant, you feel great,” the priest says. “You want to get out and do things, but you have to be careful how you interact with others so you don’t catch something.”

In time, doctors permitted him to leave his parents’ home and return to the rectory, where he met with parish staff. He was elated when more than 400 people came to the Mass of thanksgiving he eventually celebrated.

Raising Awareness

Father Mamich and Jim Lechko still nurture the friendship that blossomed during the transplant process. They occasionally go out to dinner or meet for breakfast. Father Mamich prays for Lechko every day, and when the Lechkos celebrated a milestone wedding anniversary, he attended their party.

Lechko experiences no residual effects of donating a kidney. “But Father Joe complains that he sweats all the time now,” Lechko says, laughing. “And I’m a heavy sweater. I don’t know if that came across with the kidney or not.”

Together, the two men work to raise awareness of the need for organ donation, which “fits into a consistent ethic of life. It fits nicely in the Church’s teaching on life,” Father Mamich says. “There are things we do and things we don’t do. It’s good to know both those things.” After their presentation to a Rotary group, Lechko met with an audience member who was considering organ donation. He was pleased when the young man later became an anonymous kidney donor.

Each spring, the two men address Padua Franciscan High School students in its MedTrack program, which includes four years of advanced science courses with a Franciscan approach to health care. “When I start my talks to the kids, I always say that God gave me the opportunity to do something really significant with my life,” Lechko says. “I said yes, and because of that we have a healthy Father Joe.”

“It sounds cliché, but you never know what one decision can do for someone else,” Father Mamich says.The priest, who was only 34 at the time of the transplant, says no donated organ functions forever. If tomorrow his life should end suddenly, he would still be grateful for the transplant.

“A lot of great things have happened these last four years that would not have happened if Jim had not stepped forward,” Father Mamich says.

Sidebar: The Church and Organ Donation

The US Department of Health and Human Services reports that 115,000 Americans currently await transplants of hearts, lungs, or other organs. Of these, 95,344 suffer from failing kidneys. The Church condemns the sale or trafficking of organs. In keeping with its teaching that the human body is the temple of the Holy Spirit, it presents these guidelines for voluntary organ donation:

- The benefit obtained by the organ recipient must be proportionate to the risk undertaken by a living donor.

- The donor must understand the risks involved and freely accept them.

- The donor must be able to continue living a healthy life after the transplant. For example, Jim Lechko enjoys good health with a single kidney.

In the case of deceased donors, the Church insists that:

- The donor must freely consent to organ donation prior to his/her death. Many people signal their intention through a notation on their driver’s license.

- Upon a donor’s death, his/her next of kin may choose to donate the deceased relative’s organs.

- A donor must be verifiably dead—no organs may be removed until death has occurred, i.e., organs may not be taken from persons in a permanent vegetative state.