She provided a voice to the unheard. Pope Francis acknowledged that in his speech last September to the US Congress.

Dorothy Day has been called many things. After her death in 1980, David O’Brien, writing in Commonweal, called her “the most important, interesting, and influential figure in the history of American Catholicism.” At the time, that might have seemed an audacious claim. And yet, it was amazingly prescient. Decades years later it seems not only plausible, but undoubtedly true.

Obviously, there have been many other very interesting and influential American Catholics in the last 200 years. But it would be hard to think of another American Catholic who so radically recalled the Church to its Gospel roots, while at the same time pointing exactly toward the agenda that Pope Francis has outlined for the Church in the 21st century.

In the priorities he proposed before the 2013 conclave, then-Cardinal Jorge Bergoglio spoke of the need for the Church to step outside of itself, to go to the margins and the peripheries, to touch the wounds of Christ. He has shown what that means in a Church that confronts the social structures of sin, works for peace and ecological wholeness, and embodies a spirit of mercy and reconciliation. Simply put, that is the vision that Dorothy Day embodied.

Why Dorothy Day?

Thus, it did not come as a total surprise when Pope Francis, while visiting the United States last year, invoked her name. More surprising was the context—in an address before a joint session of Congress, and among a group of “four great Americans” (including Abraham Lincoln, Martin Luther King Jr., and Thomas Merton) around whom he organized his remarks.

“In these times when social concerns are so important,” he stated, “I cannot fail to mention the Servant of God Dorothy Day, who founded the Catholic Worker movement. Her social activism, her passion for justice and for the cause of the oppressed, were inspired by the Gospel, her faith, and the example of the saints.”

I can only imagine the head-scratching in Congress and beyond that greeted these words. After all, the two Catholics he named, Day and Merton, are hardly household names. Those in Congress who did recognize her name might have been aware that Day had been called many other things besides a “great American”— such as traitor, heretic, subversive, and, of course, Communist.

She took such criticism in stride. As she often noted, it was, in her youth, the indifference of Christians toward the poor that had made her sympathize with the Communists, while it was the Communists she had known and their commitment to the poor who had prompted her conversion to Christ.

But in becoming a Catholic, Day never renounced her passion for justice. Instead, she prayed to find some way of integrating her faith and her commitment to the oppressed. She longed, as she put it, to “make a synthesis reconciling body and soul, this world and the next.”

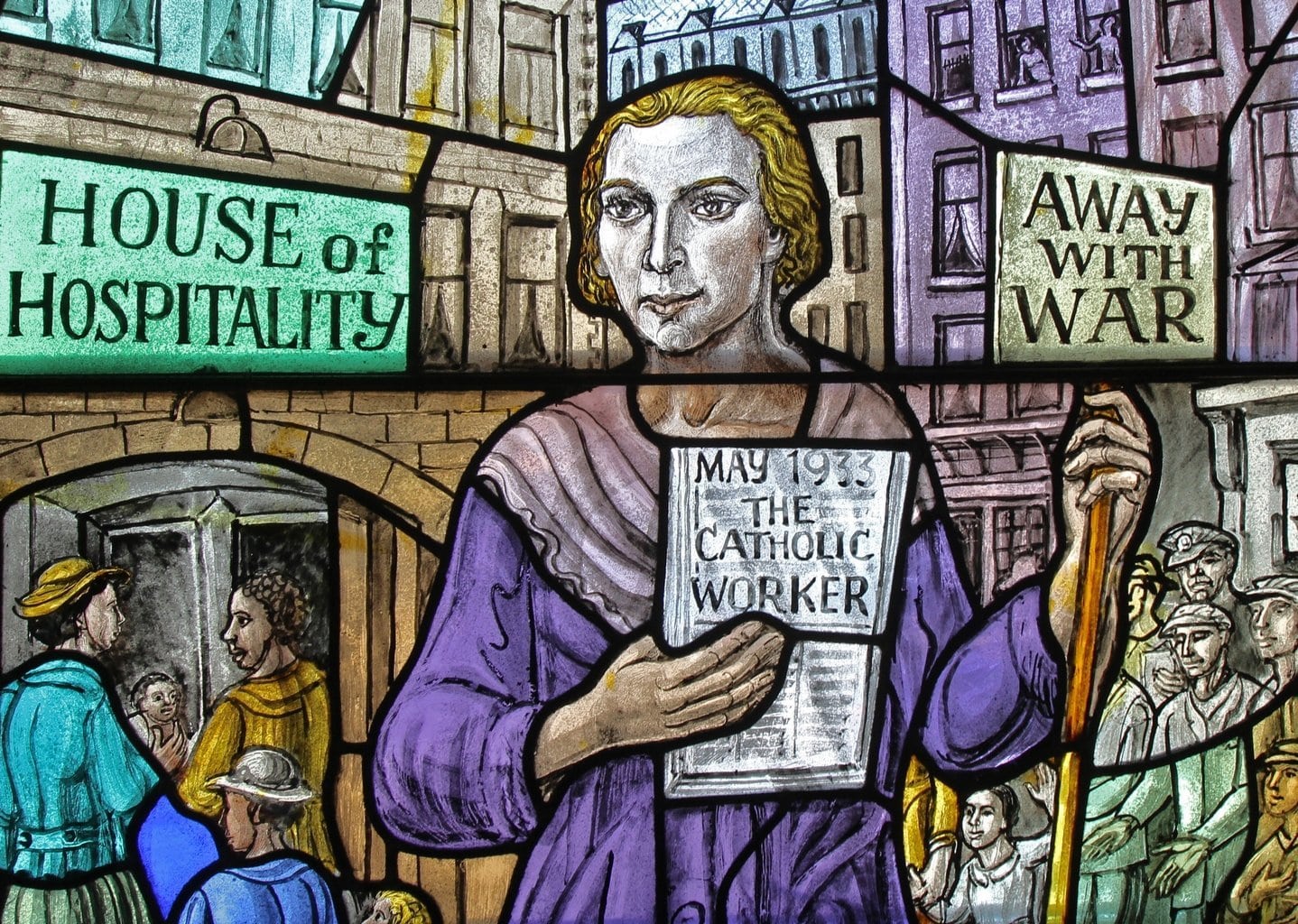

For her, the answer came in her encounter with Peter Maurin, a French peasant-philosopher, who persuaded her in 1933 to launch a newspaper, The Catholic Worker, dedicated to promoting the radical implications of the Gospel. Rather than just agitate about social injustice, articles in the paper described what society would look like if it were organized around values of solidarity, community, and human dignity instead of selfishness and greed.

But Day and Maurin believed it was not enough simply to write about these ideas; they must live them out. This led to the opening of houses of hospitality for the practice of the works of mercy—feeding the hungry, sheltering the homeless. Those who joined the work lived in voluntary poverty among the poor they served. Their manifesto was the Sermon on the Mount and the conviction that what we do for the poor we do directly to Christ.

Day, however, went further. Beyond simply caring for the poor, she believed it was also necessary to challenge, protest, and resist those social structures that cause such poverty and the need for so much charity. The seeds of this conviction extended back to her early childhood.

In her autobiography, she recalls how her heart had been stirred by stories of the saints and their charity toward the sick, the maimed, the leper. “But there was another question in my mind,” she said. “Why was so much done in remedying the evil instead of avoiding it in the first place? . . . Where were the saints to try to change the social order, not just to minister to the slaves, but to do away with slavery?”

In effect, her vocation took form around this challenge. Because of Dorothy Day, future generations of Christians would not have to ask her question: Where were the saints to try to change the social order? It was a question she answered with her own life.

Capturing Her Spirit

How could Pope Francis fail to recognize in Dorothy Day a kindred spirit? In his apostolic exhortation “Evangelii Gaudium,” he wrote in terms that might have appeared in The Catholic Worker:”Just as the commandment ‘Thou shalt not kill’ sets a clear limit in order to safeguard the value of human life, today we also have to say ‘thou shalt not’ to an economy of exclusion and inequality. Such an economy kills.” He further observed, “How can it be that it is not a news item when an elderly homeless person dies of exposure, but it is news when the stock market loses two points?”

In his first major trip outside of Rome, the pope visited the island of Lampedusa, a way station for immigrants, thousands of whom have drowned at sea. There he decried a “culture of comfort” and the “globalization of indifference” that renders us incapable of feeling the pain of others. “Who weeps for these victims?” he asked. Clearly Pope Francis does, as did Dorothy Day before him.

Before the pope’s trip to America, I had imagined the pleasure of telling him about this American Catholic who had so embraced his vision of a Church that is “poor and for the poor,” whose call for a “revolution of the heart” was echoed by his own call for a “revolution of tenderness.”

I would have described how she “touched the wounds of Christ” every day; how she spoke out and demonstrated against war and injustice, going to jail in solidarity with striking farmworkers or protesting plans for nuclear war; how she stood virtually alone among Catholics of her day in bearing witness to the Gospel message of nonviolence, the commandment to love our enemies. In light of the pope’s great encyclical on ecology, “Laudato Si’,” I would have pointed out the farming communes she established and her reverence for creation.

I would have described her spirituality, inspired so much by the “Little Way” of St. Thérèse of Lisieux, her conviction that all our small acts of faithfulness and love can help transform the world in ways we may never see. I would have told Pope Francis how Day exemplified the beatitudes; that hers is the face that comes to mind when I envision the poor of spirit, the meek, the pure of heart, the mournful, the peacemakers, and those who hunger and thirst for God’s righteousness.

But evidently no intervention on my part was necessary. Pope Francis was apparently well briefed about Dorothy Day before undertaking his trip. His references to Day, Merton, Lincoln, and King were only part of a remarkable speech in which he expressed his solidarity with immigrants (the subject of so much vilification in this political season); he called for abolition of the death penalty; he affirmed that the common good also includes the earth; he denounced the “blood-drenched ” arms trade; and he defined what it means to make America great in terms of the dreams embodied by his four great Americans.

Dorothy, Meet Pope Francis

But what, on the other hand, if I could have sat down with Dorothy Day to tell her about Pope Francis? How thrilling it would be to tell her about a pope who took his name from St. Francis and who has set out to reform and renew the Church by recalling the life and mission of Jesus and his solidarity with those on the margins. So often Day criticized the ecclesial trappings of power and privilege. How she would have delighted in Francis’ gestures of humility, his call for shepherds “who have the smell of the sheep,” his washing the feet of prisoners—including women and Muslims.

With her lifetime among the poor and discarded, how Day would have resonated with Pope Francis’ words: “I prefer a Church which is bruised, hurting, and dirty because it has been out on the streets, rather than a Church which is unhealthy from being confined and from clinging to its own security.” How moved she would be to learn of his deep friendship with a rabbi, his love for opera and Dostoyevsky, and his exhortation to spread the “joy of the Gospel.” Day always respected Church leaders. But in such a pope, I believe, she would have recognized the fulfillment of her dreams.

But there is another, personal level on which Dorothy would connect with a pope who could describe himself simply as “a sinner whom the Lord has looked upon.” Her early life was marked by her passion for social justice, but also by much sadness and moral confusion. In the aftermath of an unhappy love affair she had an abortion.

Afterward, Dorothy twice tried to commit suicide. As she wrote in her diary, “Aside from drug addiction, I committed all the sins young people commit today.” It was later, while living on Staten Island with a man she deeply loved, that she again found herself pregnant, an experience that struck her this time as a sign of God’s mercy and grace. In gratitude, she decided to become a Catholic.

It was a choice marked by great sacrifice— separation from her common-law husband, who refused to have anything to do with marriage. Looking back on all of this, she could observe, “God has been so good to me.” For Day, gratitude was the final word—for the life and faith she had been given, and for the vocation she had found.

She would have appreciated Pope Francis’ words: “I have a dogmatic certainty: God is in every person’s life. . . . Even if the life of a person has been a disaster . . . God is in this person’s life. . . . Although the life of a person is a land full of thorns and weeds, there is always a space in which the good seed can grow.” That was Day’s experience. It was God’s mercy that drew her to the Church. How could she not love a pope who has made mercy his signature theme?

In invoking Dorothy Day and his other models, Pope Francis said such individuals “offer us a way of seeing and interpreting reality.” In the context of Dorothy Day’s proposed canonization— a cause that is currently in process (see adjacent sidebar)—perhaps Pope Francis’ words help us understand what this means.

We are accustomed to thinking of saints as people who stand out for their heroic faith and witness to Gospel values. But before their bold and courageous actions, perhaps what distinguishes such people is their way of seeing and interpreting reality. They look at the world through a Gospel lens—and in doing so, they see things according to a new scale of value.

According to Pope Francis, each of the four figures he cited was animated by a dream—”for Dorothy Day, social justice and the rights of persons.” The greatness of a people, he said, is defined in part by its dreams. The same is true for the people of God.

The Road to Canonization

On November 9, 1997, the day after Dorothy Day’s 100th birthday, New York City Cardinal John O’Connor pondered the question of sainthood for Dorothy Day. He acknowledged the fact that some would object to his question of taking up the cause, but asked, “Why does the Church canonize saints? In part,” he said, “so that their person, their works, and their lives will become that much better known, and that they will encourage others to follow in their footsteps—and so the Church may say, ‘This is sanctity, this is the road to eternal life.'”

Cardinal O’Connor moved forward with Day’s cause when, in 2000, he formally requested that the Congregation for the Causes of Saints in Rome consider her canonization. Upon the congregation’s approval, Day was officially named a “Servant of God.”

In November 2012, Day’s cause was officially endorsed by the US Conference of Catholic Bishops.

The cause moved forward again this past April when the Archdiocese of New York announced a canonical inquiry into Day’s life. As part of the inquiry, the archdiocese will interview 52 eyewitnesses to Day’s life, and theological experts—appointed by Cardinal Timothy Dolan of New York—will review Day’s published works with an eye toward doctrine and morals.

According to the Dorothy Day Guild, the goal of the inquiry is to construct as closely as possible, given the passage of time, a 360-degree view of Day’s life. The Guild was established in 2005 to promote Day’s life and works.

Upon completion of the interviews, the archdiocese will send all of their information to the Vatican’s Congregation for the Causes of Saints and to Pope Francis. If, after examining the information, the congregation and Pope Francis recognize Day’s heroic virtues, she will be declared “venerable, ” the next step in the canonization process.