Praying the Way of the Cross is a familiar Lenten practice for many, but a closer look at this popular tradition reveals surprising connections to Franciscan spirituality.

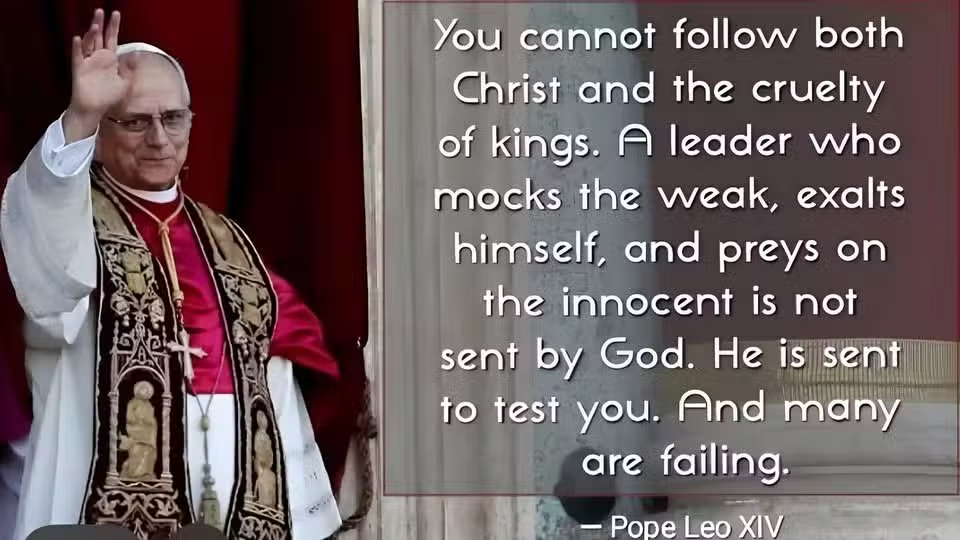

“Why did Jesus have to die?” the pastor proposed after a tirade about the fallenness and brokenness of the human race. Those at the youth conference hung in the silence he manufactured. The pastor bent down, picked up a mirror, and turned it toward the audience, “You are why Jesus had to die.” He slowly turned the mirror toward every corner of the crowd, then pointed at the crucifix suspended behind him. “Our sin—your sin—is why Jesus had to die.”

Adults sat uncomfortably in the audience, as if knowing this shame-based message could not possibly be healthy for the formative teenagers who were entrusted to their care. And yet, was this not core Christian doctrine? Who could refute the pastor’s conclusion, however harsh his delivery?

Franciscans, as we will explore, have long had a different approach to the cross, one that comes into focus during the Lenten season. Their perspective and influence is most evident in the weekly liturgical practice of the Stations of the Cross, which the Franciscans played a vital historical role in establishing.

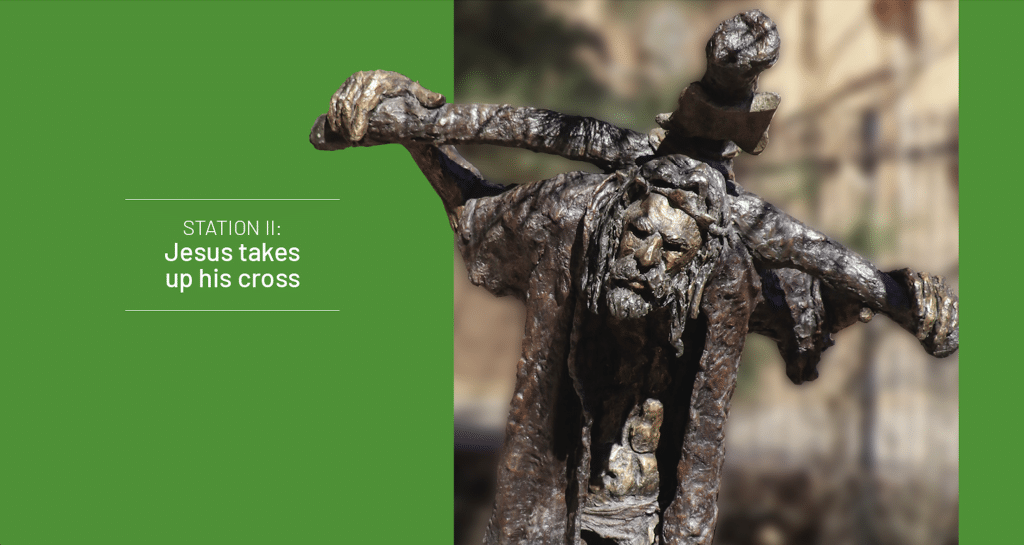

On the surface, the liturgy of the Stations—where we pray and meditate upon 14 scenes in Jesus’ route to Calvary—might not seem to align with the optimism that animates Franciscanism. The Stations mention nothing of the Resurrection and conclude with the barbaric crucifixion of an innocent man, with those who praised him on Palm Sunday now willfully joining a violent mob. Yet its history has the power to enrich our Lenten practice today and our own approaches to the cross.

The Centrality of the Incarnation

When St. Francis and St. Clare prayed before the cross in San Damiano, they were struck less by human sin and more by the humility and poverty of God, which became cornerstones of their spirituality. This God who created the universe and inhabited our world through the Incarnation was now to be experienced anywhere and everywhere: in nature, friends, strangers, stories, art, holy places, Scripture, and anything else that causes our souls to be stirred by beauty—yes, even the “other.” The Incarnation declared once and for all that the human experience in this world was sacred, for God created the world and became a human being.

All of this laid the foundation for the great Franciscan philosopher St. Bonaventure (1221–1274) to formulate an intricate metaphysics that he called “fountain fullness.” At the core of reality, Bonaventure theorized, was self-diffusive love and goodness perpetually flowing from the Trinity, like a fountain, into creation. Flowing from all eternity, this metaphysics has led some Franciscans to conclude that this fountain has deluged in two incarnations: creation (the creative action of the Word in the universe) and Jesus of Nazareth (the Word becoming flesh). This cosmic nature of the Word is detailed in the prologue of John’s Gospel and the Apostle Paul’s hymn in Colossians 1.

Today, Ilia Delio, OSF, brilliantly bridges Franciscan metaphysics with evolution when she writes: “For if sin is the reason for the Incarnation, as the Church maintains, is it possible that 14 billion years of evolving life are totally unrelated to the mystery of Christ?”

All this might sound heady or esoteric, but the Franciscan interpretation of the Incarnation would have a direct impact on shaping the Stations of the Cross.

Elevating Humanity

During the Middle Ages, Jesus was routinely depicted as a king on a throne or a victorious knight. Victory, not unlike today, was an idol. The birth of the Franciscan movement began to shift the focus back toward the humanity of Christ. In the cradle and the cross, St. Francis and St. Clare encountered a God whose core motives for the Incarnation were humility and poverty.

Franciscan Bernardino Caimi followed this same trajectory in the High Middle Ages when he erected shrines called the Jerusalem Transportata on Mt. Varallo outside Milan. These were markers for prayer designed to transport people’s hearts and minds to Jerusalem as they relived Jesus’ life and passion, an encounter with Jesus’ humility and humanity at a time when the Church grasped for power.

Father Jim Sabak, OFM, a historian and professor whose current assignment is at the Diocese of Raleigh in North Carolina, was sure to point out in his interview with St. Anthony Messenger that Bernardino was not the first to develop a practice like this. The Franciscans can be credited with popularizing the Stations of the Cross, he says, but not inventing the practice. The first on record was a fourth-century woman named Egeria, who journeyed from Gaul to Jerusalem and kept a quasi-diary of the spots she visited in the Holy Land. This eventually developed into a popular route in Jerusalem where Christian pilgrims relived Jesus’ excruciating path to Calvary. This, we might say, was the original Way of the Cross, though these pilgrimages became less common in the Middle Ages as Christian occupation of Jerusalem faltered during the Crusades. Hence, Bernardino’s Jerusalem Transportata. Why not bring Jerusalem to Milan?

Milan, at the time of Bernardino, was riddled by war and under the thumb of a Church that, as in the age of Francis and Clare, was focused on keeping its power. “Sometimes that power came through keeping people down,” Father Sabak analyzes. “The Church was kind of saying to people, ‘You’re a bunch of sinners, and you need us to make sure you don’t go to hell.’ So, again, there’s a bad anthropology and, therefore, a real need to experience the humanity of Christ, which still was not focused on enough.

“I think that, for Bernardino, the cross was a response of compassion to his situation and to the people whom the friars were ministering to in Milan. He was essentially saying, ‘You don’t suffer in vain; you don’t suffer alone; here is the Messiah, the redeemer, who suffers with you; do not forget about that.’ That, unfortunately, would get twisted into, ‘You know why he suffers? Because of sin!’ [This is] a notion that goes back to the 11th and 12th centuries. Representations of Jesus’ passion to the cross unfortunately often emphasized that we were responsible for that suffering in a bad way.”

Grace Awaits

Shame-driven and grace-driven interpretations of the Incarnation continue to collide today. The focus of early Franciscans on the humanity of Christ helped them to experience the Word in the world: in their own humanity, in the humanity of others, and in creation itself. While the Church waged a holy war on Islam, Francis sought a meeting with Sultan Malik al-Kamil in Egypt and is said to have spent several days in prayer and fellowship with him. While lepers were treated as social outcasts, Francis grew to see the dignity and rich humanity of lepers in whom his humble Christ embodied; those who were once “bitter” to him became “sweet.”

The Christology of the early Franciscans produced a positive anthropology and ecology. After all, if God created the world and became human through the Incarnation, then that meant everyone and everything had inherent dignity and could be an avenue of experiential grace.

“Francis was responding to that idea of how this victorious Christ was being manipulated for earthly victory,” Father Sabak explains. “The whole idea for the Crusades was that this risen Christ—this victorious king of all creation—wants us to kill the infidel. Francis brings us back to: Who was this human being? What did he experience? How can we connect ourselves to that? That’s what was transformational about Francis’ way of approaching God.”

Philosopher Peter Rollins once wrote a parable about a tribe of Christ followers who flee Jerusalem the day after Jesus is crucified. The members of the tribe dedicate their lives to following in the footsteps of Jesus without any idea that he had risen. Centuries later, Christian missionaries stumble upon the tribe and share with them the good news of the Resurrection. A celebration unfolds, but the chief of the tribe, with a heavy heart, wanders from the party where he is eventually confronted by one of the missionaries. As Rollins writes, this is what the chief shares with the missionary: “For over 300 years, we have followed the ways taught to us by Christ. We followed his ways faithfully, even though it cost us deeply, and we remained resolute despite the fear that death defeated him.” Holy Saturday, Rollins writes, is where our faith is forged.

The brilliance of this parable is that it stirs our imaginations to consider the humanity of Jesus without jumping to the supernatural miracle of Resurrection or our own cultural obsession with victory. Would we follow Jesus even if there was no promise of victory?

The Stations, like the parable, are a full-on confrontation with darkness and the traumas of life. Spiritual bypassing—suppressing suffering and adopting trite explanations for suffering—is not an option when the liturgy of Stations is taken seriously. We are challenged to live our story from the “middle,” trusting that, even amid descent and unknowing, we are still moving. Awed by the raw humanity of Christ, we confront our own humanity and the sacred humanity of others in the process.

Movement through Fear

A special connection to Jesus’ passion, which began with Francis’ conversion before the San Damiano cross and culminated in his receiving of the stigmata at the end of his life, continued to evolve for the Franciscans. In 1342, the pope placed Franciscans in charge of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre (where Jesus was crucified) and the Via Crucis (the Way of the Cross) in Jerusalem. At the turn of the 18th century, St. Leonard of Port Maurice, an Italian friar, began promoting the Stations of the Cross and erected them at nearly 600 sites across Italy. This popularity led the pope to propagate the prayer practice as 14 official stations in 1731. The Stations of the Cross could be established at any holy site as long as they were blessed by a Franciscan.

“St. Leonard was ministering and writing in the aftermath of the Reformation and the breakdown of Christianity,” Father Sabak explains. “So, for him, to try to reunify Christianity was to remember this man, Jesus, who died, who was more important than the conflicting ideas between the Catholics and reformers who were dividing the Church. It was to remember who was at the source. It wasn’t the pope. It wasn’t kings or princes. It wasn’t doctrines or dogmas. It was Christ, this Christ who suffers and dies. In praying the Stations, he was saying to focus on the one who holds us together, even in death. It isn’t to be prayed, ‘I’m responsible for Jesus’ death, I’m responsible for Jesus’ death, forgive me, forgive me.’ Rather, it was to be prayed so that you knew the anchor and root of our faith.”

Though the Franciscans had their own rite for the Way of the Cross, the ritual today is more connected to St. Alphonsus Liguori (1696–1787), an oblate of St. Francis de Sales, whose way of praying further popularized the Way of the Cross. After Vatican II (1962–1965) and the revision of the Roman Ritual, the Joint Commission of Catholic Bishops’ Conferences published the Book of Blessings, which permitted laypeople to bless and pray the Way of the Cross themselves.

This is a fitting “conclusion” to the history of the Stations of the Cross and the threads of Franciscan involvement throughout the centuries, for that was the point of the ritual all along: for anyone, anywhere to embark on a holy pilgrimage; for anyone, anywhere to walk in the footsteps of Jesus. The point is not to masochistically remove Jesus from heaven and place him back on the cross, but rather to identify with the fullness of his humanity in his darkest hours and mirror him in how we move through our own suffering.

“What does it mean to be a believer who stands before the pain, hurt, terror, and anger of the world?” Father Sabak asks. “Jesus faces all that pain and hopelessness yet is unafraid and moves forward. How do we face our fears and not be afraid? Because we trust that God knows what God is doing with us, just as Jesus did.”

Movement is our offering—our prayer—in the Stations of the Cross and in life. Whereas shame and despair can be paralyzing, the Way of the Cross stirs us to move authentically through our own suffering, even if it feels sometimes as if we are spiraling further into chaos. Our faith is what animates this movement, for we can trust a Christ who did not come to explain suffering, but rather entered more fully into its very depths as a human being. Even if we are not physically moving through the Stations, as has been the ancient practice, our hearts and minds are invited to move through gazing, considering, contemplating, and imitating the cross, as St. Clare once wrote to Agnes of Prague. In another letter to Agnes, Clare suggests to “place your mind before the mirror of eternity.”

In the Way of the Cross, we are invited into this same dynamic, as the mirror reflects back to us who we are to become: more like this radically humble God, just as God became like us. The mirror, as we find, holds us.