“Not me, but God,” Blessed Carlo Acutis is quoted as saying. When this author visited Assisi, she discovered the growing excitement surrounding the millennial teenager’s life, legacy, and sainthood cause.

In the sunny Piazza del Comune, the center square of Assisi, I shift over on the stairs away from the ancient two-tiered fountain because when the spring wind gusts, I get blessed with its falling water droplets. I fall into a cheerful conversation with a group of already sunburned Irish people sitting under an umbrella at the cafe, declining their invitation to take a chair at their table several times, then I shyly join when they keep insisting.

“I’m Maeve. That’s Nora, Finn, and Barry.”

I say my own name and clap my hand over my heart for emphasis, having barely spoken to anyone in English for three days, and relying instead on exaggerated gestures and pantomime to communicate.

“Maureen?” Maeve asks. “Are you Irish, then?”

“Partly. Maureen Mary Mary O’Brien, because my Protestant mom didn’t know that a Catholic Confirmation name wasn’t supposed to be the same as the child’s middle name.”

They all laugh and tell me they are in Italy to celebrate Nora’s 50th birthday, which happened two years ago, but they had to cancel the plans until now due to the pandemic. I nod. My feelings about my own 50th birthday are a silent predawn inside me: I awoke in Hartford Hospital to my surgeon telling me he got the pathology report that morning, and I would need more surgery, but he believed he got all the cancer out. I was given a second chance, first with addiction, then with cancer, my life now a double doublet.

They’re quite inquisitive about me and enthusiastic about the book I’m writing when I tell them why I am in Assisi all alone. They’re clever conversationalists and leap around topics with wit and curiosity. One of my favorite things about traveling is that friendships are accelerated, forming very fast. They are from Northern Ireland, and Barry explains to me—a quick sketch of the Troubles—the conflict between Protestants and Catholics. They ask me about being Catholic in America, and I tell them my Franciscan church is welcoming of the gay community, and he feels comfortable enough to confide that he and Finn “are together.”

We end up laughing about how all Irish families, even ones with watered-down Irish genes, seem to be stocked with secrets. I connect Nora’s name to the wife of the great Irish writer James Joyce. I’m ridiculously proud of the fact that Barry is visibly impressed when I brag about how I didn’t skip a single word of all 856 pages of Ulysses.

“How did you do that, Maureen?” he liltingly jokes.

Meet Carlo Acutis

We only have a few hours before their train returns to Rome. “Have you seen Carlo Acutis?” Maeve asks.

I shake my head. “No, who?”

“The teenager. From Italy. The soccer player who died of cancer. They say more people are coming to Assisi to see him than even Francis.”

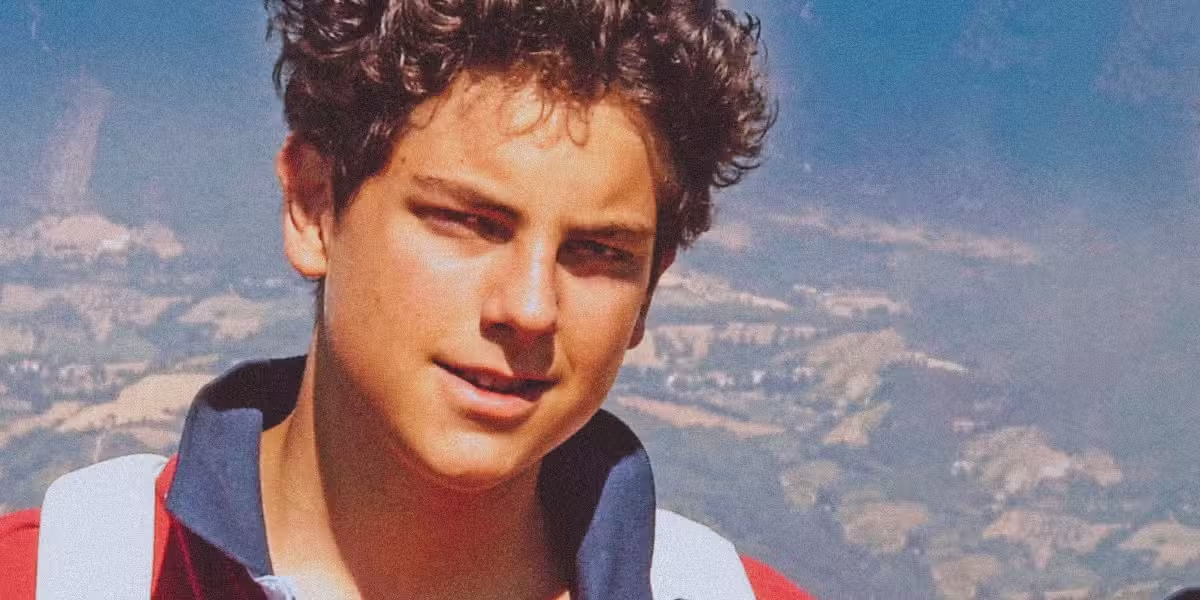

“Oh! That’s who that is?” I’d noticed flyers taped on the front windows of the religious tchotchke shops selling all variations of St. Francis and St. Clare. I knew nothing about this boy holding the viewer’s gaze, squinting into both the sun and the camera, cropped shiny black curls, the geometric fields of the Italian countryside far below him, and two wide straps of his backpack on either shoulder. Underneath his portrait it read “Non io ma Dio,” but I didn’t know what that meant.

“His body is in Santa Maria Maggiore,” Maeve continues. “He died at 15, having an extraordinary faith, Maureen. He had spent his life designing a website devoted to recording the hundreds of miracles of the Eucharist. His devotion was of the real presence of Jesus in the Eucharist. He wasn’t even from a religious family! He went to church every day as a child. He’s always pictured with his backpack. That’s his sign. Do you want to go there with us now?”

“Absolutely.”

We gather our things from the table, and I happily follow them down the piazza and through side streets to the church. A crowd chatters inside excitedly despite signs reading “Silenzio.” A white marble coffin, with Carlo inside, is raised up on pillars and illuminated. A homespun wreath of family photos is displayed nearby on the floor. Just like the ritual of a funeral, the images of his holidays, sporting events, all the captured childhood moments are plucked straight from his mother’s photo albums.

In the ornate sarcophagus in which he lies, the front panels can slide open and show him in repose. In order to discourage crowds, these panels have been shut during COVID-19.

When he was beatified—becoming officially “Blessed,” one step short of sainthood—at the Basilica of St. Francis here, over 40,000 came to this town in the course of three weeks. I am relieved I cannot see him in there. Though really, what is the difference between his remains and those of St. Clare in her crypt that I just viewed a few hours ago? That he is simply more recently dead? This veneration in Catholicism fills me with contradictions. I find it shocking, weirdly thrilling, comforting, repellent, and fascinating.

At the end of the room is a life-size cardboard cutout of him with a human-size chalice and Eucharist. I’m sorry to say it seems tacky to me, like a cutout you’d have at a high school graduation. Though who am I to judge, since he never even got to have a graduation? People are posing in front of the sarcophagus. Mostly Italians, a few international tourists. So many of us wear sneakers to church now. I’m always amazed at the older ladies with big beads who still wear pantyhose and pumps with chunky heels to dress with respect; they kiss their hands then lovingly touch Carlo’s marble sides.

Silenzio

Expressing my faith with brand-new friends nourishes me. Back home, I spend a good deal of time in my friendships alone with it, in silenzio. It’s exhilarating to worship together, and because we’re all on holiday, it’s fun. I’m not shy to bow my head with them as we sit together on a bench. Maeve takes blank sheets of paper and pens near the sarcophagus to write our individual intentions. We scribble, then fold the papers in half and quarters and slip them, with all the others left by people seeking change and healing, into a plastic box, half full.

I place my left hand upon his crypt, palm fully open. It’s refreshingly cold, soothing the relentless heat of the brokenness I’ve endured in the dust and screws of my deformed wrist for nearly a decade.

They only have a short time left. They want to see Clare, and we head down to the basilica. Nora and I share that we both wrote intentions for our children. “It was also very strange, Maureen, because just as I was writing a prayer for her, she called me,” Nora says.

“She felt it,” Maeve reassures her.

Walking with them down the street, the men ahead, it seems it’s always been this way, the five of us joking around and crossing ourselves unabashedly as we enter churches. It’s why I feel that Assisi is my home. I can be the holy fool that I am and not think twice about hiding it or defending myself. Beginning my day at one of the basilicas, blessing myself over and over, kneeling and whispering prayers into my woven hands, then I go to San Rufino and bless myself, whisper some more, not caring who sees because no one thinks I’m a weirdo as they, too, are worshiping. They, too, believe.

I stop by San Stefano Church in the middle of Communion and get in line, then later in the day, walk into Santa Maria while a rosary is being said, and I join in.

Too soon, we must part. Maeve hugs me. “Maureen, come see us in Ireland.” How I would love to go, having only been once, but I know there’s limited time now in my life to return to the faraway places I’ve fallen in love with.

The Physical Signs of Devotion

I climb back up Via S. Rufino to my apartment and do some research. I have to laugh because, once again, I’m the blind man not fully seeing. I’ll always be a bit of a Mr. Magoo. Apparently, I was just in a church where a powerfully historic event occurred. Carlo Acutis lies in the Santuario della Spogliazione, the Shrine of the Stripping. The site where, in front of his father, Francis threw off his luxurious clothes, renounced the wealth of his family, and stood naked, choosing to follow Christ. No gold, no money, haversack, shoes, no more than one tunic.

I learn the boy’s heart is now a relic. Relics: a strange practice, yet I’m transfixed. A piece of Carlo’s pericardium, a bit of this sac, is traveling to waiting congregations around the world. So now, while I am in Italy near his bones, a fragment of this beatified boy is back in my country, in New York City. We’ve crisscrossed on our flight paths.

Whatever one thinks of this practice, and I am not always quite sure myself, I am left with the image of this boy’s heart. My heart. The Sacred Heart. The sac that holds our hearts in place in our bodies, enclosing our hearts and the roots of our vessels. There’s an outer layer and an inner double layer—a double doublet within us all.

A relic is defined as something that remains, left over, a portion. Bones, objects, clothing, not just in Christianity, but in Buddhism and Hinduism too. It can be something kept for sentimental reasons, which makes me think we all have relics. I wonder what you have? What jewelry of loved ones who have passed do you hang on your body? What objects of theirs do you house?

I do understand that the idea of relics, of death or impermanence, creates a desire to look away. Some people never look at it at all. My mother, at 85, is looking. The week before I came to Italy, I went to see her in Maine.

“I might not be here much longer,” she said as we toured all the trees in her yard. Should she bother pruning them? “I’m not going to worry about it,” she decided as she poked her cane in the center softness of a stump. There was, perhaps, resignation, but not any bitterness in her voice. Just the truth. And surrender.

Later, slumped on her couch with the heating pad relieving the pain of a hairline fracture in her spine, she asked me, “What do people do with all their stuff?” Genuinely wondering as she looked about her home of the last 30 years. All the furniture, books, doodads. Her husband has died before her, so she now surveyed their 62 years together. Upstairs, she placed the urn with my father’s ashes, his Purple Heart from Korea, and a black-and-white photo of him lined up, on the top row, holding the American flag for Platoon 80.

I tried to reassure her. I’ve thought about this quite a bit myself, trying to minimize what my children might have to do for me after I go. “I mean, it’s true, Mom, when someone dies, someone has to tend to the stuff after them. Everyone leaves something behind, right? Unless we live in a monastery with nothing, but even then, someone has to figure out what to do with the bed.” It’s a fairly ridiculous viewpoint, and we laughed.

That night of my visit, I found solitude in the lamplight as my mother slept, and I realized what made her saddest was that the objects in her house had sentimental value. Much of her conversations consist of, “That was my mother’s” or “That was Grandma Mann’s.” Her walls are decorated with the work of her grandmother, framed cross-stitches of strawberries and sparrows with phrases such as, “Warm friendship like the golden sun shines kindly light on everyone.” And my favorite, “Leave no tender word unsaid, love while life shall last.”

The Sweetness of Sanctuary

And now, in Italy, far from my mother’s relics, I’m close to other ones. Assisi’s two main churches are the Basilica of St. Francis and the Basilica of St. Clare. In the bottom of each lie the saint’s bones. I have been here many days, and the bells ring all day, every 15 minutes, and are silent at night when I believe these churches, one at each end of the town, are the paperweights holding down the edges of the winds that encircle the earth.

Francis has a double basilica that, I swear, every sunset, has rays of sun fanning wide from the clouds floating above it (I have proof). The lower Romanesque part was built in 1230, and atop that, the upper basilica, Gothic in style, completed in 1253. The whole cathedral borders on ineffable; it surrounds me, soars above me, fills the sky. But I also know the wonder in the little, and in the corner of the ornate lower basilica, tiny stitches whisper to me from St. Francis’ tunic, the one he once wore, protected, pressed flat under glass. Yellow tracks run wildly all over the course brown fabric, covering it in patches and rips, like flaps repaired.

The frescoes inside, by Cimabue and his pupil Giotto, took another hundred years to paint. I go to bask in their energy every morning and night. The church closes at 7:00 p.m. Italians don’t heed time like Americans, so the guard is visibly annoyed with me as I slide into the church at 6:50. He’s done. The evening has turned cold with rain, and he wants to close up shop. But I have 10 minutes! The guard has waved everyone out, sighing, but allows me to slip through.

He doesn’t even bother to keep his eye on me as he wanders out the doors. I look around for silhouettes of people, but there’s no one. I am alone. Tourists from all over the world flock here in droves all day, but now, here I am, in the most exalted church in the whole world, and for 60 seconds, I am given the unexpected gift of having this entire basilica to myself. Half the lights are already turned off. Its emptiness I would not describe as quiet or tranquil. What is it? It’s sweet. It’s absolute sweetness.

I am underneath one of the most perfect frescoes ever painted, S. Francesco Riceve le Stimmate (St. Francis Receives the Stigmata). The wounds of Jesus. Floating above Francis, Jesus is part bird, part angel, arms open, feathered wings spread wide. His face is erased from the two earthquakes that struck, the double tremor, in 1997. People were tragically killed here, and many of these frescoes were destroyed. It adds to the powerful understanding of impermanence. And fragility.

The guard returns and shoos me out with the Italian word for “closing.” He doesn’t care that I think this Giotto fresco is beautiful. And I don’t care that he doesn’t care. I’m emboldened by my glorious stolen moment. I tell him it’s beautiful anyway.

It’s midnight. I feel the relics out there, a gilded triptych. Clare, Carlo, Francis. It fills me with the desire to find them, not just while awake but always, even in my dreams. I write to Francis in my journal: “Let me dream tonight of the stitches in your tunic, the knots holding your patches together; let me dream tonight of your arms wide open in the moonlight.”

And the miracles, all of them, move forward, as miracles do, and this new one, a boy who believed, who chronicled miracles about holy bread. Just a kid! Just a kid, a child who gave all he had to God until the very end. It was Blessed Carlo Acutis, perhaps soon-to-be a saint, who said, “Non io ma Dio” (which I learn means, “Not me, but God”). And perhaps one day there will be statues of him in the back of the basilicas, but Blessed Carlo is already guiding us with the straps of his school backpack and his pair of black Nikes.

17 thoughts on “Carlo Acutis: Miracles, Holy Bread, and a Teen Saint in the Making ”

Blessed Carlo Acutis, prày for us 🙏 St. Francis,friend of my childhood Pray for us, especially my loved ones ❤️🙏🙏🙏🙏❤️

ORA PRO NOBIS !👏🙏

St. Anthony, my family needs multiple miracles. Please pray and ask that my husband, Joe Simon, will be cleared of any cancer, tumors, or any other health issues., restoration of his health, body, mind, and soul. And for my daughter who is in an abusive marriage, that she and her son, Shelby and Leo, will be protected and delivered from this situation. Please pray for a 💯 conversion of her husband, Oscar Varon, that his eyes will be opened, ears unplugged, and hard, stubborn,prideful,disrespectful heart transformed, converted so he can see the damage he is doing to his family and repent and convert. For Oscar to be delivered from his addiction to his phone and computer and that whatever he and his family are hiding will be revealed. Pray that Jesus will place a wall of protection around Shelby and Leo and shower them with all of The Gifts and Fruits of The Holy Spirit and many, many miracles of healing, body, mind, soul, and opportunity for a great job opportunity so that Shelby and Leo will never be parted, 💯 custody of Leo to Shelby. Miracles for a beautiful holy marriage and permanent conversion of Oscar. Respect for those who God has placed in his path to help him, who he is rejecting. For Oscar to embrace the vocation of a holy, sacrificial husband and father. Deliverance from love of money, miserliness, and self centered selfishness. Praying total healing for our family and scars from the past

I have great devition for catlo I talked to him he’s a brother I never had !! He does appear to me I hear his voice once I heard him played the saxophone very softly I was quite surprised

ST. ANTHONY PLZ. PRAY FOR MY SISTER TO SEEK AND FIND LOVE,PEACE,HAPPINESS AND A JOB. PRAY FOR MY NEIGHBOR WHO IS SUFFERING WITH HIS MEMORY PROBLEMS AND AND HOW TO TALK. PLEASE PRAY FOR MY BROTHER WHOS FEET GIVE HIM PROBLEMS TO WALK. AND LASTLY….FOR MYSELF.I TRY NOT FOCUS ON MYSELF AND FEEL THAT OTHERS SUFFER MORE THAN ME. BUT I DO NEED PRAYER…MY SPINE,BACK AND LEGS. I NEED PHYSICAL RESTORATION. THANK YOU ST. FRANCIS.AMEN

Please save my mum Saint Carlo.I believe in You.Please save her.Please Heal her (Carmen Turcitu Barbaroussis).Please show the doctors what is wrong with her and save her.Please Saint Carlo Acutis.I believe in You.Thank you 🙏🏿

Dear: St. Carlo: I only just heard about you when they interviewed your mother on TV. Please help my husband who has been battling health issues for the last 25 years. Please help me to take care of him for I am 83 years old. Please pray for my youngest brother who was diagnosed with ALL. I will pray to you daily. I believe in you. I LOVE YOU. THANK YOU

Dear St Carlo, please pray for me and all those like me ,who are suffering from cancer. Please intercede for us all, help us in our daily needs. Please touch all spots of cancer and let them shrink and fade away, that we might be strong and healed again. Thank you St Carlo. Amen 🙏

Our Lord God loves the sinner not the sin; it isn’t the role of any representative of God here on earth, to give blessings to Gay relationships.

I have loved my Carlo from the first time I saw him. I call him my Carlo because he feels like my own. My grandson has been under his protection almost from the first time I saw Carlo. Please my Carlo protect my family and pray for their salvation.

Dear St Carlo please pray for my nephew Rodney and cure him of his cancer and intercede for me with the Almighty God to spare him from this disease and accord him a few more years with his young family Amen 🙏

Wonderful readings and something spiritually has overcome me! Please bless my mother Natalie Loera as she recovers from a severe Stroke. Teresa🌺

Please bring my children and grandchildren to Jesus

Pray for my granddaughter Ruby, not yet born. I pray that she stays close to her maker and leads her family to love.

Dear St. Carlo,

please bless us with a healthy baby, we’ve been struggling with infertility for more than 3 years.

please pray for us. Thank You

Is he really in the very spot of the famous “stripping”?

I know a lot of people think the reason for his current appeal (and canonization) has to do with his Internet outreach. I believe it is mainly a sign: Il Poverello was a rich young man who gave up everything for Christ.

Carlo was a rich young man who similarly was drawn to Christ through no doing of his parents.

The eye of the needle–the impossible–behind done by God’s hand, a work of beauty and grace. May it inspire us to trust more completely in the work of God.

St. Carlos Acutis intercede for my Son Luyando so that he can grow in the love of God, Jesus, the Holy Spirit and our blessed Mother Mary who he has already show devotion to. I also ask you to keep my wife Victoria health as she goes to Uganda for her studies. May my sons liking of technology be a source of blessing.