Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. stood on a platform few people of color were given during the civil rights movement and dared to demand a life better than what they were living. And like a visionary with eyes affixed on the horizon, he stood on the precipice of social change and said, in a tone laden with hope, “I have a dream.”

The dream outlived the dreamer after an assassin’s bullet took his life in April 1968. That act of violence stopped the revolutionary, but it could not halt the revolution: the march for freedom continued in King’s formidable shadow. It marches to this day, now with Black Lives Matter (BLM), an activist movement that campaigns against violence toward African Americans. And while the group has become a lightning rod in political circles, especially after the 2020 killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, its existence proves how important King’s work was—and how unfinished it is.

Progress through Peace

Dr. King’s influence is still felt five decades after he was murdered. Pope Francis singled him out, along with Abraham Lincoln, Dorothy Day, and Thomas Merton, as a model American.

“A nation can be considered great when it . . . fosters a culture which enables people to ‘dream’ of full rights for all their brothers and sisters, as Martin Luther King sought to do,” the pope told Congress in September 2015. He was spot-on, but he neglected to mention the methods by which the civil rights leader sought freedom. Dr. King advocated for peaceful resistance, even when mobs in the Jim Crow South used violence to keep equality from taking root.

BLM employs an even stronger confrontational method to address racial issues than its civil rights—a kind of “discourse by way of discomfort.” Activists have also resorted to “die-ins,” where protesters clog sidewalks by pretending to be dead. Political rallies, marathons, and other large-scale events have been disrupted by the group. Their mission—if not their tactics—have been supported by the Journal of Humanistic Psychology, which stated, “In the United States, the message seems clear: Black lives do not matter equally to White lives. Systemic racism with the barrage of racial micro-aggressions remind Blacks daily of their unimportance and reinforce White privilege.”

Dream On

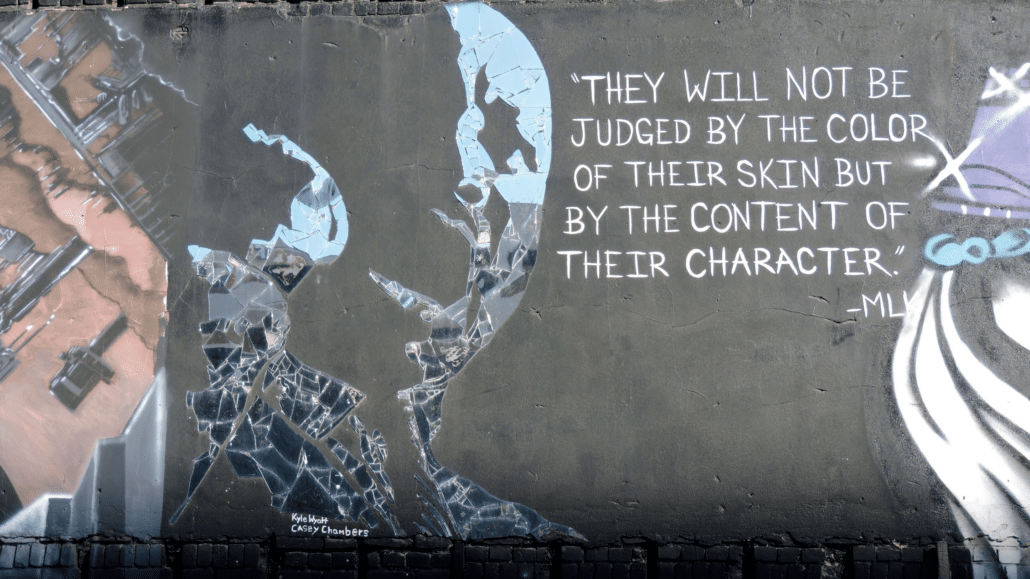

When King delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech in 1963, 250,000 people in DC stood spellbound. It is perhaps the most important oration of the 20th century. The true punch of the speech is its inclusionary message. King dreamed of a day when “little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers.” That is a statement infused with Gospel truth: love your neighbor.

Our pope is clearly moved by the man. “That dream continues to inspire us all. I am happy that America continues to be, for many, a land of ‘dreams,’” he told Congress. “Dreams which awaken what is deepest and truest in the life of a people.”

Has King’s dream been realized? While we’ve made strides in the ensuing decades, the BLM protests in 2020 demand a closer look. As Americans, King’s dream should be our mission. As Christians, it should be our mandate. The march to Selma never ended. We must continue the journey until “all of God’s children, black men and white men, Jews and gentiles, Protestants and Catholics” stand shoulder to shoulder, looking out at the same horizon Dr. King eyed with brazen hope.

That is still a dream worth fighting for.