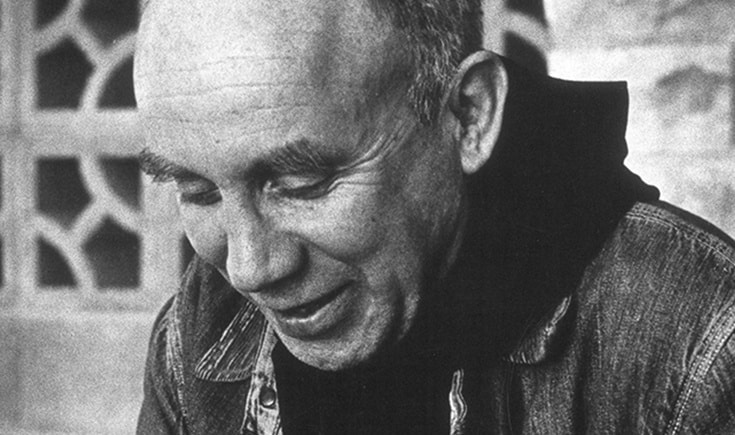

I only saw Thomas Merton once. He walked in front of my family and me when we were visiting the Abbey of Gethsemani in early June 1961. I had read Sign of Jonah and Waters of Siloe in the high school seminary in Cincinnati, and already my youthful mind intuitively knew that this man was a prophet for my soul and for the Church in the world. So, on the day of my graduation and return to Kansas for the summer, I said to my parents, “Let’s take the southern route home. I have a place I want you to see.” Little did I imagine!

I stood back in awe as he walked two sisters and their driver right in front of us. He was returning them to their car as we approached the old guesthouse. One of the sisters was Mother Teresa of Calcutta.

When I later gave a retreat at the abbey, in 1985, I asked one of the brothers if I was just imagining this, and he said with a bit of disappointment (or was it resentment?), “Oh, we all heard that ‘the famous sister from India’ was visiting, but, of course, none of us got to meet her except the abbot and probably him!”

A Modern-Day Prophet

Yes, I believe Thomas Merton was a true prophet, and I use that word in its classic sense, as one who sees at a higher level and thus, in effect, foresees. A biblical prophet is one who lives on the edge of organized religion as a truth speaker, and yet from the loving and experienced depths of that religion.

He cannot be throwing rocks from outside, but must “pay his dues” and earn the right to speak what are—somehow—words from elsewhere! The message is invariably mystical and political at the very same time; it is a “synthesis of seeing” that God grants to anyone God chooses to speak prophetically.

I am now convinced this is what religious life is meant to structurally allow and even foster—a prophetic and listening stance as opposed to a merely priestly one. Monks, nuns, hermits, and friars are a part of para-church communities, each with different things to pay attention to, various spiritualities that encourage depth and actual God encounter, and authority structures that protect, allow, and foster just such wisdom.

Religious life is structurally set up to be “a room with a view,” and often a view that the common parish does not have time to inspire or generate. No wonder that the young man raced to a place like Gethsemani with such determination, fervor, and even overexcitement.

A prophet intuitively knows that he or she cannot stand alone, but needs the wisdom and protection of a living faith community, and years of the deep listening and loving that many forms of religious life can ideally provide. What the prophet has to say is going to “uproot and knock down, destroy and overthrow, build and plant” (Jer 1:10), and in ways that scare into doubt the one who is saying it. No wonder that Moses stutters, Jeremiah beg out of the role, and Isaiah’s lips are burnt with a live coal; no wonder John the Baptist must leave his priestly family for the alternative food and clothing of the wilderness.

This man, like almost no one else in our time, put together the mystical depths and the political implications of the Christian message. He did it in a way that confirmed for many of us a kind of “deep Christianity.” He wrote things that still now are showing themselves to be true and even central to spiritual truth.

I find him read in every country and continent I have taught in, and quoted by sincere seekers of all Christian denominations and even other religions. Things he wrote in the 1950s and ’60s do not always feel dated. This surely means we are dealing with big truth and high-level seeing.

Although there are so many aspects of the wisdom tradition that he recovered, there is only one that I want to comment on here. I believe that he almost singlehandedly pulled back the veil and helped us see that we all had lost the older tradition of contemplation. It was no longer taught in any systematic way in the Church. Clergy, religious, and laity “recited” prayers and meticulously “performed” liturgies, but the older methods for quieting the mind and heart, and seeing “spiritual things spiritually” (1 Cor 2:13), had been lost in both theory and practice by almost all of us, even the contemplative orders.

It was nobody’s bad will, but simply what happened after we separated from the Eastern Church in 1054, and then allowed the dualistic and calculating mind to take over after the Reformation and the wrongly named Enlightenment.

The Contemplative Mind

In that same 1985 retreat that I mentioned, I asked my friend Brother Robert Bruno if the monks liked Thomas Merton, because I had picked up what seemed like a bit of “no prophet being honored in his own country” or what could have been in-house jealousy from a few. Robert humbly and quietly said that it was true that many did not like him so much in the community. I asked, “But why?” And these were his words: “He told us that we were not really contemplatives! We were just introverts!”

But, of course, he was pointing out the elephant in the monastic living room, as prophets are wont to do. Even contemplatives had no systematic training in what to do with their obsessive minds and errant emotions, just as Teresa of Avila had already complained in the 16th century. No one told them exactly “how” to deal with the distractions that followed them into the monastery.

The daily schedule and monastic habit, and lots of chanted psalms, did not usually eliminate their old mind, their lonely hearts, and their unhealed emotions. Mere willpower and goodwill itself were not enough to do the spiritual warfare that they had entered into. Many left all forms of religious life, feeling they had been overpromised, deceived, or worse, that there was no accessible God to be found.

If we should place a monument for this holy man anywhere, it would be enough if it just said, “He gave us back the contemplative mind. He told us, and he showed us, that we could live with the very ‘mind of Christ’ (1 Cor 2:16).”

Lasting Impact

“I want to see him as someone who’s very much like all of us,” says Jonathan Montaldo, internationally recognized writer, editor, and retreat presenter. “If you want to call him a saint, that’s fine, but what does it mean? He’s a person who struggled to do the will of God, who realized his faults. His clay feet are there for all of us to see.

“He certainly would not want any kind of adulation given to him in the way of sainthood. He once had a letter from a young man who said that he wanted to become his disciple, and he wrote back and said, ‘Don’t try to be. I don’t have disciples. I don’t want any disciples. Don’t build your life on a mud pile like me. Be a disciple of Jesus Christ.’”

He has become for many people the person whose writings they turn to for spiritual direction. This is something he did not intend and did not want. He once wrote to a correspondent that he had no disciples. He wanted no disciples. He thought he could be of no help to disciples. Become, he suggested to this correspondent, a disciple of Christ.

Yet, whether he wanted it or not, through his many writings, he has directed the spiritual journey of so many people whose names we shall never know: people who are in communion with institutional forms of religion and, perhaps most astounding of all, people whose only link with spirituality is the monk who lived in Nelson County, Kentucky, in the Trappist monastery of Gethsemani.

A Love for All People

People were precious to Thomas Merton: He respected their uniqueness. One need only read his many letters to see how he makes every effort to identify with others and find common ground on which they can comfortably meet. He was convinced that the ultimate ground in which we all meet is that “Hidden Ground of Love” we call God. God can be named in many ways, yet God always remains mystery that no words of ours can ever grasp.

To Merton the name of preference was Mercy. “God,” he wrote, “is like a calm sea of mercy” (Seasons of Celebration, p. 120). In the wonderful conclusion of The Sign of Jonas, he has God speak: “I have always overshadowed Jonas with My mercy….Have you had sight of Me, Jonas My child? Mercy within mercy within mercy” (p. 362). For many people, brought up with the notion of a God who is judge, rewarding and punishing almost unfeelingly, approaching the divine as mystery of mercy can be a source of light and joy.

Not only does he seek common ground with those to whom he relates, but he also responds to people in their uniqueness. Thus, his letters to Dorothy Day, for instance, have quite a different tone from those he wrote to Daniel Berrigan. He was at once strong and gentle in his relationships. John Stier, an American government official who was his host in Sri Lanka, said that Merton made a tremendous impression on him. As they discussed Buddhism, Stier soon learned that Merton was much better informed about this religious tradition than he was. Merton disagreed with him when he expressed the opinion that Buddhism was a negative approach to life.

But, Stier says of him, “He was surprisingly gentle in disagreement. He had a wonderful way about him”—a shrewd observation with which hundreds of his correspondents would express wholehearted agreement.

Timeline of Thomas Merton

1915 Born to Owen and Ruth Merton on January 31 in Prades, France, and later moves to New York.

1918 John Paul Merton is born.

1921 Ruth dies.

1926-28 Thomas lives in France with his father.

1928-34 Studies in England (including the 1933-34 year at Clare College in Cambridge University.)

1931 Owen dies.

1935-39 Studies English at Columbia University, earning a BA and MA.

1938 Baptized at Corpus Christi Church in Manhattan and later starts to consider a vocation to religious life.

1940-41 Teaches English at St. Bonaventure University in western New York.

1941 Enters the Abbey of Our Lady of Gethsemani in December.

1943 John Paul Merton, a pilot, dies over the English Channel.

1948 Seven Storey Mountain (his autobiography) is published and quickly becomes an international best-seller.

1949 Ordained a priest and becomes a US citizen.

1950-60s Serves in various offices at the Abbey, maintains a huge correspondence, writes over 70 books and numerous articles, and becomes active in the civil rights and peace movements.

1965 Moves into a hermitage at Gethsemani.

1968 Visits Sri Lanka and India before attending an interfaith monastic conference in Bangkok. Is accidentally electrocuted on December 10. Buried at Gethsemani.

Click here for more on Thomas Merton!