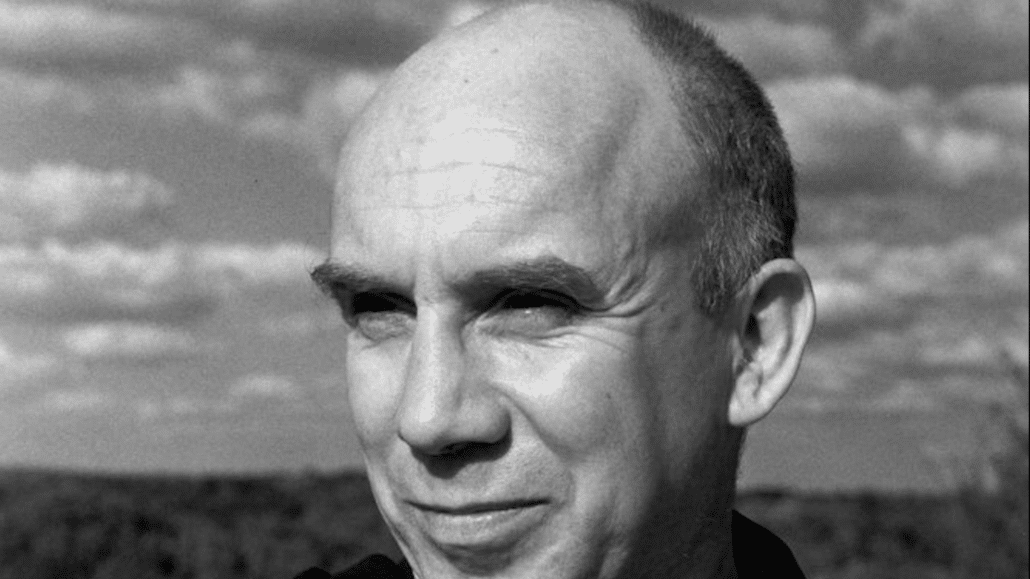

On November 10, 1958, Thomas Merton wrote a letter to Pope John XXIII in which the famous American monk shared with the new pope some reflections about the world and Church. In one part, Merton describes how he has begun to understand that being a cloistered monk does not necessarily mean withdrawing from the world in an absolute sort of way.

Instead, he has discerned the Spirit calling him to another form of ministry from within the walls of the monastery by writing letters, connecting with women and men that he might never have had the opportunity to meet otherwise.

It is not enough for me to think of the apostolic value of prayer and penance; I also have to think in terms of a contemplative grasp of the political, intellectual, artistic, and social movements of this world—by which I mean a sympathy for the honest aspirations of so many intellectuals everywhere in the world and the terrible problems they have to face. I have had the experience of seeing that this kind of understanding and friendly sympathy, on the part of a monk who really understands them, has produced striking effects among artists, writers, publishers, poets, etc., who have become my friends without my having to leave the cloister.… In short, with the approval of my superiors, I have exercised an apostolate—small and limited though it be—within a circle of intellectuals from other parts of the world; and it has been quite simply an apostolate of friendship (Thomas Merton, “Letter to Pope John XXIII” (November 10, 1958), in The Hidden Ground of Love: Letters, ed. William H. Shannon (New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1985), 482).

Merton came to realize that part of his religious vocation involved connecting with people of different backgrounds, experiences, and world views. He corresponded with the writers Boris Pasternak, Czesław Miłosz, Ernesto Cardenal, and Evelyn Waugh; with activists Joan Baez, Daniel and Philip Berrigan; with theologians Paul Tillich, Karl Rahner, Abraham Heschel, and Rosemary Radford Reuther; with bishops, nuns, and religious leaders of other traditions, like Thich Nhat Hanh; and with so many others including ordinary, unknown people.

I thought of Merton and his “apostolate of friendship” a couple years ago while sitting at a pub one evening in England. I was in the company of a diverse collection of people: a middle-aged father from Ireland, an Episcopalian priest from Scotland, and a woman and man from England, both teachers. We were there enjoying some beer after a long but inspiring day of academic presentations and workshops on the life, thought, and legacy of this American monk. We were in Oakham in central Britain for the Thomas Merton Society of Great Britain and Ireland conference, an event held every other year. (On each alternating year, the International Thomas Merton Society holds a large conference somewhere in North America.) I was there to deliver a keynote address, but the conference draws a diverse group composed of top Merton scholars, those with a more casual interest in Merton, and all sorts of people in between.

The Seven Storey Mountain

Strangers before this evening, those with whom I found myself at the pub all began to exchange stories about how each came to discover the writings of Merton and what had led them to attend this three-day event. Most shared a version of the typical Merton story, which begins with reading The Seven Storey Mountain. However, the Irish man recalled a dramatic event that took place in a hospital room. Visiting his father, who was recovering from surgery, he was told that the man in the next bed was dying. The dying man happened to be reading a book, which led my new Irish friend to reflect: “If he’s dying and is reading, it must be an amazing book! I need to know what it is.”

The book was Merton’s The Seven Storey Mountain. Decades later, this Irish man shared that Merton remained a major influence in his life ever since he read the book after that hospital encounter. Few writers and thinkers have such an ability to bring people together. Even fewer long after their death. In 1958, it was Merton who wrote to the pope, but in 2015 it was Pope Francis who would hold up Merton as an exemplar of Christian living during his historic address to the United States Congress.

In part, it was Merton’s reaching out to engage in friendship with so many people that led Pope Francis to the monk who had died nearly a half century earlier. Pope Francis told Congress and the world, “Merton was above all a man of prayer, a thinker who challenged the certitudes of his time and opened new horizons for souls and for the Church. He was also a man of dialogue, a promoter of peace between peoples and religions.” Pope Francis also held Merton up as a model for his own ministry, stating, “It is my duty to build bridges and to help all men and women, in any way possible, to do the same.”

Thomas Merton continues to exercise an “apostolate of friendship,” bringing people together across many divides. If you haven’t met Merton and his friends yet, I encourage you to do so.

11 thoughts on “The Friends of Thomas Merton”

I have read that Thomas Merton had a great influence on one of my favorite spiritual writers, Henri Nouwen.

Thomas Merton had a lot to offer. I think, though, he was at the point of getting too involved with Eastern religions so GOD took him home to protect him & us from going too far.

I don’t think any of us know God’s will. Merton did much to enlighten us on the ways of God. Let us offer prayers and thanks to him and not idle speculation.

Thank you, Michael, for your interpretation. I have just recently become intrigued and interested in the intellectual influence of Thomas Merton. I look forward to further study.

Sal G.

If God would do such a thing—which He wouldn’t—and even that is presuming to know the deep workings of the Spirit—then He would have also taken our beloved St. Francis and other saintly people who have “touched the hem of the Lord’s cloak” and been healed. Did not Francis “go too far” in the eyes of the world? Did not Christ himself first “go too far” in the eyes of the world to do the same to unite us as the children of God?

Big difference. Every step St. Francis of Assisi took brought him deeper into the GOSPEL & in love for & with JESUS CHRIST.

Thomas Merton was moving in the direction of Eastern religions, which could have led him & others astray & contrary to Church teaching.

Thomas Merton wrote & did much good & that should never be denied. I especially love his prayer about his desire to do GOD’S will & please GOD, trusting that GOD would show him the way even if he could not see it & relief in knowing that his desire to please GOD does in itself please Him. I found that prayer very helpful when I was going through a career transition.

GOD did not cause Thomas Merton’s accident, but I believe He used it to take him home & prevent him from going astray & leading others astray. We can & should have respect for people seeking GOD in non-Christian religions & what we have in common. but at the same time we need to be wary of adapting their practices. The New Age movement that incorporates practices of Eastern religions is dangerous because it can invite the involvement of spirits that are not of the LORD. I think the LORD ensured that Thomas Merton would not get himself & others burned by playing with fire.

My thoughts are not unscriptural. St. Paul in his letter to the Corinthians commented that many of their number had “fallen asleep” because of their lack of discernment in their behavior regarding the Eucharist. They were not condemned but brought safely home.

“Going too far”?. Merton tragically died from an accident.

I too read the book Seven Story Mountain. I think the book is overrated. Thomas Merton was a good guy nevertheless. The only reason I read the book is because a journalist from the Minneapolis Tribune wrote an article on Blessed Fr. Kelly, who I encountered when I was nine years old, mentioned Thomas Merton’s book Seven Story Mountain in his article. I found that article lying around my house twenty years ago, and the mentioning of that book piqued my interest.

So, what was Thomas Merton looking for in his life? I guess his lost innocence and holiness, perhaps. He apparently ended up dying in a bathing accident in Thailand, if my memory serves me correctly. He thought the Buddhists and the Christian monks had something in common. But do they really, other than asceticism? I think trying to convert Buddhists to Christianity is a fool’s errand. One could just as easily bang one’s head against the wall and achieve the same affect. Remember, belief is an emotional thing. You can’t convince someone that Christianity is the true faith and only true faith, if they have an emotional investment in another belief system and way of life. Religion, after all, is nothing more than a way of life. Who are we to say our way of life is superior to theirs when an honest observer will notice that when it comes to sin, we too are stuck with the same life issues. So, explain to me, why they should accept your belief system pertaining to your God?

If he was seeking to convert Buddhists to Christianity, that would have been the right path, & so would have been focusing on what both faiths have in common to lead them ultimately to the fullness of truth.

I think the problem was that he was in danger of incorporating too much of Eastern practices & diluting the true faith.

Mutual respect & acknowledging what is good & what we have in common: YES. Acknowledging that people in other faiths are seeking GOD: YES. But careful discernment is necessary & ultimately everyone seeking GOD need to be shown the One they are seeking: JESUS CHRIST, the Way, the Truth & the Life.

Merton is like the sun. Long after it has set it fills the horizon with a glow!

I’m not sure that anyone can ever “Go too far” in seeking God through other faiths or other denominations or even other traditions. My God seems to be found Everwhere we look for Her.

I believe Merton had/has the ability of helping many on their journey. That alone I believe to be wondrous. Amen!