The deep friendship and rich dialogue between St. Francis of Assisi and Sultan Malik al-Kamil centuries ago can inform interfaith dialogue in our own times.

Toward the year 1219, the relations of the Little Poor Man with his followers were no longer the same. Up to this time, almost everyone had followed him as a venerated father and infallible oracle. But from now on, many would oppose his ideal and attempt to evade his authority. It was inevitable that, growing and spreading as it did, the Brotherhood should become less homogeneous and less fervent.

The friars who had received their training at Rivo Torto were now submerged in the mass. The immense majority of the Order was composed of religious who had not been formed by St. Francis.

A great many hardly knew him. The superiors or ministers were recruited for the most part among the outstanding and influential clerics, to many of whom it was repugnant to be led by “a man without learning,” a man indeed considered an impractical and even dangerous visionary by some prelates in high places

Certainly, in coming to the Chapter of 1219, these ministers did not bring with them a definite reform slate; but they nonetheless made no effort to conceal their dissatisfaction and their own inclinations. What they wanted, in fine, was for the Order to bear a closer resemblance to other religious congregations, to be able to devote themselves to study, to practice a poverty less strict, and to profit by ecclesiastical favors.

They had a good opportunity, for instance, to show how the friars, for lack of official references, had been expelled from countries of the Empire and were threatened with a similar fate in France. Now, if Francis did not reproach others for having recourse to Bulls, exemptions, and privileges, he himself would have none of them. It was not his idea to be either protected or preserved. Had not his beloved Christ been compelled to flee before his enemies? Had he availed himself of immunity and protection at the scourging and crucifixion?

So, far from displeasing him, persecution which made him like to our Lord delighted him. This was the concept he instilled into Brother Leo, giving him the most astounding definition of perfect joy that men had heard since the Gospel passage: Blessed are they who suffer persecution. The famous dialogue must have taken place about this time.

Together with the Canticle of the Sun, it constitutes St. Francis’s masterpiece. To the religiously minded of all time, the Poverello repeats that it is not in performing wonders, but in sacrifice and suffering that man’s true nobility and earthly happiness consist.

“Brother Leo, God’s Little Sheep, take your pen. I am going to dictate something to you,” declared Francis.

“I am ready, Father.”

“You are going to write what perfect joy is.”

“Gladly, Father!”

“Well, then, supposing a messenger comes and tells us that all the doctors of Paris have entered the Order. Write that this would not give us perfect joy. And supposing that the same messenger were to tell us that all the bishops, archbishops, and prelates of the whole world, and likewise the kings of France and England, have become Friars Minor, that would still be no reason for having perfect joy. And supposing that my friars had gone to the infidels and converted them to the last man….”

“Yes, Father?”

“Even then, Brother Leo, this would still not be perfect joy. If the Friars Minor had the gift of miracles and could give light to the blind and hearing to the deaf, speech to the dumb, and life to men four days dead, if they were to speak all languages and know the secrets of men’s consciences and of the future, and were to know by heart everything that has been written since the beginning of the world until now, and were to know the course of the stars, the location of buried treasure, the natures of birds, fishes, rocks, and all creatures, understand and write it on your paper, Brother Leo, that this would still not be perfect joy.”

“Father! For the love of God, please tell me then just what is perfect joy?”

“I’ll tell you. Supposing that in the winter, coming back from Perugia, I arrive in pitch darkness at the Portiuncula. Icicles are clinging to my habit and making my legs bleed. Covered with mud and snow, starving and freezing, I shout and knock for a long time. ‘Who is there?’ asks the porter when he finally decides to come. ‘It is I, Brother Francis.’ But he doesn’t recognize my voice. ‘Off with you, prankster!’ he replies.

“‘This is no time for jokes!’ I insist, but he won’t listen. ‘Will you be off, you rascal? There are enough of us without you! And there is no use in your coming here. Smart men like us don’t need idiots like you around. Go, try your luck at the Crosiers’ hospice!’

“Once more, I beg him not to leave me outside on a night like that, and implore him to open up. He opens up, all right. ‘Just you wait, impudent cur! I’ll teach you some manners!’ And, grabbing a knobby club, he jumps on me, seizes me by the hood, and drags me through the snow, beating me and wounding me with all the knobs in his cudgel…. Well, Leo, if I am able to bear all this for love of God, not only with patience but with happiness, convinced that I deserve no other treatment, know, remember, and write down on your paper, God’s Little Sheep, that at last I have found perfect joy.”

Among the friars present at St. Mary of the Angels in 1219, there were a certain number who would have preferred joys less perfect, convents less poverty-stricken, and in general more comfort and security. Was it this year that Francis, on arriving at the Chapter, was surprised to discover a stone edifice suddenly sprung up alongside St. Mary of the Angels? At any rate, he was indignant. What? In this dear Portiuncula that was to serve as a model to the whole brotherhood, they had dared to make a mock of holy poverty? It was in vain that the culprits explained that this new building was owing to the solicitude of the Assisians.

Climbing at once on the roof, and calling on his friars to help, the saint began hurling down the tiles. It was plain to be seen that this was only the beginning; and to keep the whole building from being torn down, the friars shouted to the knights of Assisi, who stood close by, ready to intervene.

“Brother,” they remonstrated. “In the name of the commune we represent, and which is the owner of the building, we implore you to stop!”

“Since this house belongs to you,” Francis replied, “I have no right to touch it.” And sick at heart, he broke off his work.

A still more painful scene occurred one day when “several wise and learned friars got Cardinal Hugolin to urge Francis to be guided by the wiser brethren.” To their way of thinking, it was from the way of life of Sts. Benedict, Augustine, or Bernard that inspiration for revising the statutes of the Brotherhood should be taken. The cardinal carried their request to the saint. Francis made no reply, but taking the prelate by the hand, he presented himself with him before the Chapter.

“Brothers! Brothers!” he cried, overcome by emotion, “the way that I have entered is one of humility and simplicity! If it is a new way, know that it was taught me by God Himself, and that I will follow no other. So do not speak to me about the Rules of St. Benedict, St. Augustine, or St. Bernard. The Lord wishes me to be a new kind of fool in this world, and will not lead me by any other way. As for you, may He confound you with your wisdom and learning, and make the ministers of His wrath compel you to return to your vocation, should you dare to leave it!”

These maledictions terrified the assembly and even the cardinal; and this time, at least, no one dared to insist.

The Chapter of 1219 maintained the decisions relative to the division of the Order in provinces. Their number was even increased, since France from then on had three provinces. Friars were appointed to go to Christian lands where they had not yet penetrated or to return to those from which they had been driven. But the great innovation of this Chapter was the creation of missions in foreign lands.

Brother Giles left for Tunis, where the Christians of the city, fearing that his zeal might compromise them, thrust him in a boat to force his return. Great was his disappointment at seeing the crown of martyrdom escape him; but he consoled himself when it was given him to realize that certain vexations of the devil outdid all other tortures in cruelty. Other friars, whom we shall meet soon again, headed for Morocco. Francis himself, ever eager to shed his blood for Christ, chose to go to Egypt.

After appointing two vicars to replace him at the head of the Brotherhood, Francis left the Portiuncula at the beginning of June and went to Ancona to take passage on one of the ships conveying crusaders to the East. A large number of friars accompanied him, but not all of them could be accommodated.

Francis said to them, “Since the sailors refuse to take all of you, and since I, who love you all equally, haven’t the heart to make a choice, let us ask God to manifest His will to us.” Calling a young boy who was playing on the wharf, he asked him to point out twelve friars at random, and it was with them that he embarked. Among them were Peter Catanii, the former jurist, Illuminato of Rieti and Leonard, two former knights, and Brother Barbaro, one of the first disciples.

They set sail on June 24, 1219, St. John’s Day, and first put into port at the island of Cyprus. They reached St. John d’Acre about the middle of July, and a few days later Damietta in the Nile delta, which had been under siege by the crusaders for a year. Duke Leopold of Austria, their leader, had all sorts of men under his command. If some had taken the cross out of holy zeal, many were mere adventurers, attracted to the Orient by the hope of pillage and pleasure. The license and disunity reigning in this army was sufficient explanation of its previous failures.

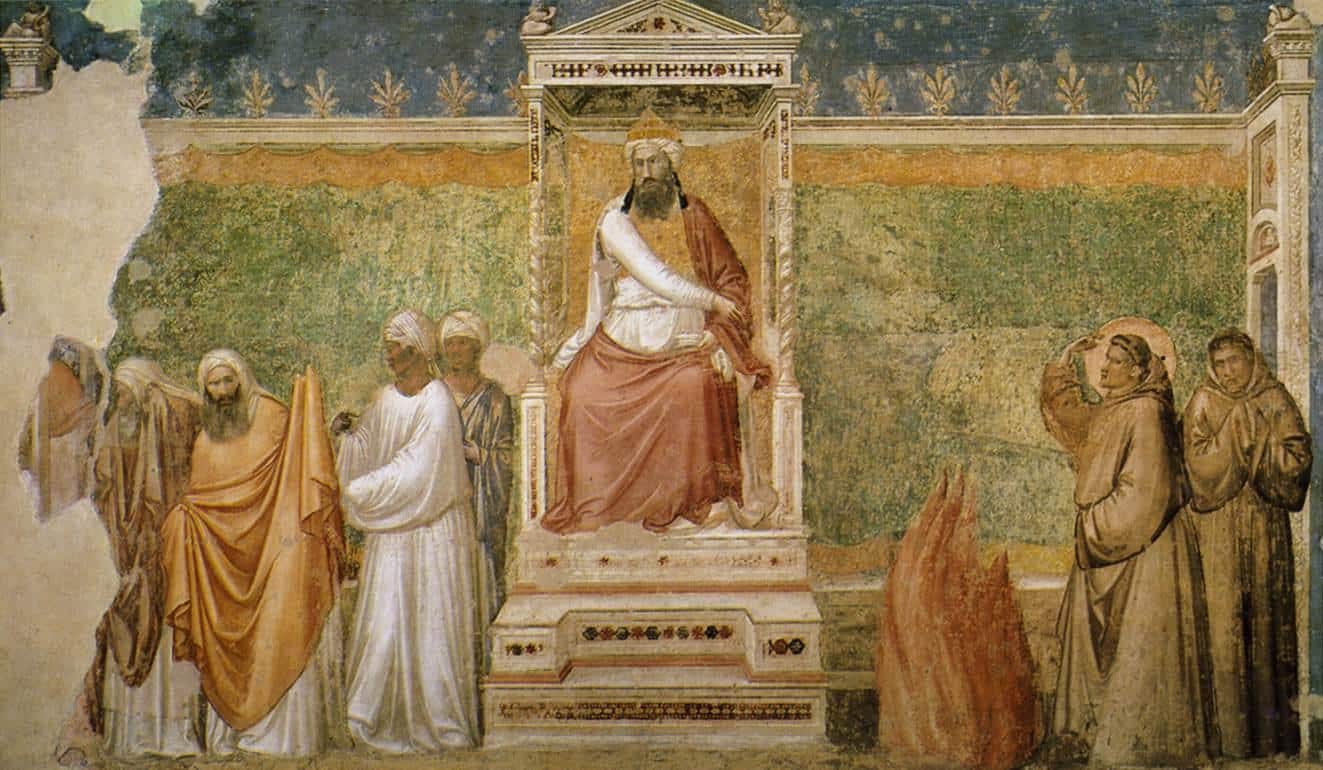

Meeting the Sultan

When, on the morning of August 29, Francis learned that the army was going to attempt a decisive assault, he said to his companion, “The Lord has revealed to me that the Christians are running into a new defeat. Should I warn them? If I speak, they will call me crazy. If I keep still, my conscience will reproach me. What do you think, Brother?”

“The judgment of men matters little!” replied his companion. “After all, this will not be the first time you have been taken for a madman! Unburden your conscience then, and tell them the truth!”

The leaders mocked Francis’s warnings and the attack took place. The result was, as we know, a disaster in which the crusaders lost over four thousand men, killed or captured. Francis had not the heart to witness the battle; but he sent messengers three times for news. When his companion came to him to announce the defeat, he wept much, says Thomas of Celano, especially over the Spanish knights whose bravery had led nearly all of them to their deaths.

The saint remained there for several months. At first, his apostolate among the crusaders had marvelous results. He was hailed as a prophet ever since, in opposition to the leader, he had dared to predict defeat. His courage and knightly bearing filled the warriors with admiration and his guilelessness and charm won their hearts. “He is so amiable that he is venerated by all,” wrote Jacques de Vitry to his friends in Lorraine.

The celebrated chronicler who at that period occupied the episcopal see of St. John D’Acre and made frequent visits to the crusaders’ camp, added that many abandoned the profession of arms or the secular priesthood to become Friars Minor. “This Order which is spreading through the whole world,” he wrote further, “imitates the primitive Church and the life of the Apostles in all things.

Colin the Englishman, our clerk, has entered their ranks, with two others, Master Michael and Dom Matthew, to whom I had entrusted the parish of the Holy Cross. Only with difficulty do I hold back the Chanter and Henry and others.” Jacques de Vitry also announced to his correspondents that “Brother Francis has not feared to leave the Christian army to go to the enemy camp to preach the faith.”

The idea of converting the Saracens must have appeared singularly fantastic to men who up to then had thought only of cutting their throats. It is true that the Moors asked only to do likewise; for, quite apart from an eternal reward, every Muslim who brought a Christian head to the Sultan received a golden bezant from him. Cardinal Pelagio, who now arrived in Damietta with reinforcements, was far from encouraging Francis in his project. If not actually forbidding the undertaking, he at least declined all personal responsibility, charging Francis not to compromise thereby the Christian name and Christian interests.

The saint took Brother Illuminato with him and set out toward the enemy lines, singing, “Though I walk in the midst of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil, for Thou art with me.” To comfort his less reassured companion, Francis showed him two ewes peacefully grazing in this perilous spot. “Courage, Brother!” he cried joyously. “Put your trust in Him who sends us forth like sheep in the midst of wolves.”

However, the Saracens appeared, jumped on the two religious, and began to beat them. “Soldan! Soldan!” shouted Francis as long as he was able. The soldiers thought that they were dealing with envoys and brought them in chains to their camp. Francis explained in French that he desired to see the Sultan and convert him to the Gospel. Had he said this anywhere else, it would have meant instant death; but the court of Al-Malik al-Kamil included skeptics who liked to discuss the respective merits of the Koran and the Gospel, and who likewise were chivalrous in their deportment.

The Sultan also doubtless saw in the arrival of the Friars Minor an opportunity for diversion and ordered the evangelizers to be shown in. It is said that in order to cause them embarrassment, he had a carpet strewn with crosses laid down in the room in front of him. “If they walk on it,” he said, “I will accuse them of insulting their God. If they refuse, I will reproach them for not wishing to approach me and of insulting me.”

Francis walked unhesitatingly over the carpet, and as the prince observed that he was trampling the Christian cross underfoot, the saint replied: “You must know that there were several crosses on Calvary, the cross of Christ and those of the two thieves, the first is ours, which we adore. As for the others, we gladly leave them to you, and have no scruples about treading on them, whenever it please you to strew them on the ground.”

Al-Malik al-Kamil soon conceived a warm friendship for the Poverello and invited him to stay with him. “I would do so gladly,” replied the saint, “if you would consent to become converted to Christ together with your people.” And he even offered, writes St. Bonaventure, to undergo the ordeal by fire in his presence.

“Let a great furnace be lit,” said he. “Your priests and I will enter it; and you shall judge by what you see which of our two religions is the holiest and truest.”

“I greatly fear that my priest will refuse to accompany you into the furnace,” observed the Sultan.

And indeed, at the simple announcement of this proposal, the venerable dean of that priestly group hastily disappeared. “Since that is the way things are,” said Francis, “I will enter the fire alone. If I perish, you must lay it to my sins. But if God’s power protects me, do you promise to acknowledge Christ as the true God and Savior?”

The Sultan alleged the impossibility of his changing his religion without alienating his people. But as his desire to keep this charming messenger at his court was as strong as ever, he offered him rich presents. These were, as we may well imagine, refused. “Take them at least to give to the poor!” he urged. But Francis accepted, it appears, only a horn which later on he used to summon people when he was about to preach.

He departed very sad as soon as he perceived the uselessness of his efforts. The Sultan had him conducted in state back to the Christian camp. “Remember me in your prayers,” he begged as Francis left, “and may God, by your intercession, reveal to me which belief is more pleasing to Him.”

Thanks to the reinforcements of Cardinal Pelagio, Damietta fell on November 5, 1219. Francis was present at the taking of the city; but this victory of the crusaders drew more tears from him than did their recent defeat. The streets were strewn with corpses and the houses filled with victims of the plague. The captors fought like wolves over the immense booty, selling the captives at auction, except the young women reserved for their pleasure.

When Francis saw that Damietta had become a pandemonium in which his voice was lost in the clamor of unleashed instincts, the saint left the country and took ship for St. John d’Acre. There he met Brother Elias, Provincial of Syria, and among Elias’s recruits, Caesar of Speyer who had fled Germany to escape the relatives of those whom he had enrolled in the crusade and the husbands of the women he had converted.

It was also at St. John d’Acre that Francis learned that five of his sons had just shed their blood for the faith. They were Brothers Otho, Bernard, Peter, Accursus, and Adjutus, who had left the Portiuncula at the same time he did; and who, as we have seen, set out for Morocco by way of Spain.

Bridges Built

Truly these five had left no stone unturned to obtain the grace of martyrdom. Arriving first in Seville, which was still in the power of the Moors, they had entered the mosque and began to preach. It was a good place to meet Muslims, but a bad one in which to insult their prophet, Mohammed. They were hustled out and beaten. They then went to the royal palace.

“Who are you?” the king asked them.

“We belong to the regions of Rome.”

“And what are you doing here?”

“We have come to preach faith in Jesus Christ so that you may obtain everlasting life like us.”

The prince, beside himself with fury, ordered them to be beheaded; but seeing the joy his sentence caused them, he took pity on them and attempted to win them by presents. “May your money go to perdition with you!” they replied.

They were taken in chains to the summit of a tower. They were then shut up in the public prison where they still attempted to convert their jailors and fellow prisoners. They were again brought before the king, who gave them the choice of returning to Italy or of being deported to Morocco. “Do whatever pleases you,” they replied, “and may God’s will be done!” It was decided that they should go to Morocco.

Shortly after their arrival, the Amir al-Muminin Yusuf, who commanded in Africa in the king’s name, had them brought before him, half-naked and in chains. “Who are you?” he asked.

“We are disciples of Brother Francis, who has sent his friars throughout the world to teach all men the way of truth.”

“And what is this way?”

Brother Otho, who was a priest, began to recite the Creed; and he was starting to comment on it, when the Miramolin stopped him, saying, “It is surely the devil who speaks by your mouth.” He thereupon handed them over to his torturers. These used their cruelest devices against their victims. All night long the poor friars were flogged until they bled, dragged by the throat over pebbles, and doused with boiling oil and vinegar, while, their hearts failing them, they exhorted one another in a loud voice to persevere in the love of Christ.

The following day, January 16, 1220, the Miramolin summoned them at dawn to learn if they persisted in despising the Koran. All proclaimed that there is no other truth than the holy Gospels. The prince threatened them with death. “Our bodies are in your power,” they replied, “but our souls are in the power of God.”

These were their last words, for Abu-Jacob thereupon had his sword brought and cut off their heads in the presence of his women attendants. When these facts were reported to Francis, he is said to have exclaimed, “Now I can truly say that I have five Friars Minor.” But when the account of their martyrdom was read before him, he interrupted the reading as soon as he perceived that a few words praising him had been inserted.

Syria, at this period, was partly Christian and partly Muslim. Thanks to a permit received from Conradin, Sultan of Damascus and brother of Al-Malik al-Kamil, Francis could travel anywhere in the country without paying tribute. He made use of this privilege, says Angelo Clareno, to visit the Holy Places.

How we would like to have a contemporary account of those who saw him or accompanied him to Palestine—showing us the Little Poor Man celebrating Christmas in Bethlehem, weeping on Good Friday at Gethsemane and Calvary, and communicating on Easter morning at the Holy Sepulchre! But, unfortunately, the records are silent about these months in the life of St. Francis.

They only break the silence again to state that during the summer of 1220, an emissary from the Portiuncula named Brother Stephen arrived in Syria bearing bad news. His message was that the vicars were leading the Order to ruin, and that the faithful friars implored their father, if he was still of this world, to come back at once and save his work.

Sultan Francis Sultan Francis Sultan Francis Sultan Francis Sultan Francis Sultan Francis Sultan Francis Sultan Francis Sultan Francis Sultan Francis Sultan Francis Sultan Francis Sultan Francis Sultan Francis Sultan Francis Sultan Francis Sultan Francis Sultan Francis Sultan Francis Sultan Francis Sultan Francis Sultan Francis Sultan Francis Sultan Francis Sultan Francis Sultan Francis Sultan Francis Sultan Francis