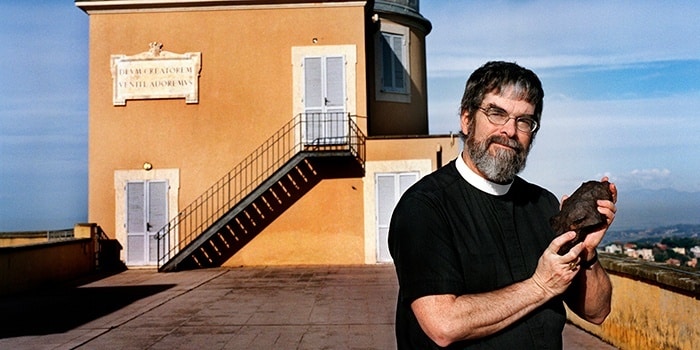

Vatican astronomer Guy Consolmagno explores the heavens in search of higher meaning.

Jesuit Brother Guy Consolmagno, director of the Vatican Observatory since 2015, finds it altogether baffling that some people still see science and religion as being somehow opposed. “The hardest thing I have to deal with,” he tells St. Anthony Messenger, “is trying to figure out where people are coming from when they don’t see them as a natural fit. That is mysterious. Why would anybody think they’re conflicted? It’s like asking, ‘How can you be a fan of the New York Knicks and also drink Coca-Cola?'”

People think of both science and religion as “big books of facts,” he says. “Everything about that description is wrong.” Our scientific understanding “constantly changes, constantly grows.” The same is true for religion. If it were a book of facts, he says, “You could just memorize it; you wouldn’t have to practice it. Both science and religion are taking what we thought we knew and trying to understand it.”

The Jesuit teacher wraps it up with a quick lesson: The “grand war” between reason and faith, he explains, “was invented at the end of the 19th century. It had nothing to do with Galileo. It had nothing to do with Giordano Bruno. It was a political invention to serve the secular interests of the day. In Europe, secular governments saw the Church as a threat and wanted to bash it. In America, the politics of the day was controlled by people who saw immigrants from central and eastern Europe as threats to the American way. The excuse to keep them out was that they were ignorant; their religion was against science.”

The science of the 19th century was profoundly influential in every area of life. “We had electricity and steam engines that looked like they were going to solve all of our problems.” While technology is terrifically useful, Brother Guy says, it doesn’t solve the real problems, the human problems. For example, “There was this wonderful understanding of how life evolved that Darwin had come up with, and people used that and abused that to support their own horrible ideas. Whether it was social Darwinism, which said helping the poor was hopeless because they are naturally inferior, or the hideous racism that said we can eugenically create the master race—we eventually found where that led. “

Looking Up

Even if science and religion go hand in hand, Brother Guy often hears from those who still think it strange that the Church has an observatory. People ask him, “Why does the Vatican have a space program?” He tells them, “The dangerous answer is: Why would anyone? Why does the US government care about space?”

Detroit-born, Brother Guy says his first love was science, but he always grappled with the big questions, whether astronomical or philosophical. “I was a researcher at MIT [Massachusetts Institute of Technology], 30 years old; I was a PhD, a postdoctoral fellow. And I would lie awake at night asking, ‘Why am I wasting my life studying astronomy? There are people starving in the world! Couldn’t I be doing something more useful than this?’ I quit astronomy. I quit science. And I joined the Peace Corps,” where he was sent to Africa, teaching astronomy at the University of Nairobi, in Kenya.

This seemed an odd turn for someone who had left research academia behind for a more hands-on approach to doing good in the world. Brother Guy says: “Every weekend, I would go up-country to where my fellow volunteers were teaching—in the small schools, in the little villages—and I would give a little talk about astronomy and set up my telescope. Everybody in the village would look at the moon through the telescope.

“It finally dawned on me: this is an important part of being a human being, to have this curiosity—about the universe, who we are, where we come from, how it all fits. We have to feed that curiosity. We have to feed our souls. You have to feed your intellect, or else you’re nothing more than a well-fed cow.”

After all, he says, “we don’t live by bread alone.” And we have to admit, too, “that the answer is not simply, ‘God did it.'” The religion that offers that simplistic answer for every question, he says—brace yourself—is paganism. “But we’re Christians; we have rejected the pagan gods. We believe in a God who decided to create and the first thing he creates is light—so he’s doing nothing hidden, nothing in the dark. God says that everything he has created is good. He invites us, his creation, to enjoy it, and one way of enjoying it is learning how it works.”

The sense of wonder at the created world is certainly familiar to Franciscans. Brother Guy thinks Francis of Assisi can teach us a lot about how to look at the world. “G.K. Chesterton said that the way the pagans looked at nature was to view it as a cruel mother; and the way that Francis looks at nature is as a sister—and not just a sister, but a little sister. A dancing, joyful little kid who you can laugh at and love.

It was Albert Einstein who said, “The amazing thing about the universe is that it can be understood.”

“Nature is not something that controls us or that we control,” he says, “but it is our sibling, to be loved and cared for. More than that, science teaches us a really important lesson: even things that look chaotic can be understood. That there are things that seem to be out of our control, but that we can control. When we encounter problems in life, you don’t blame the gods. You ask, ‘How can I make things better?'”

It was Albert Einstein, reminds this astronomer, who said, “The amazing thing about the universe is that it can be understood.”

How to Understand the Universe

A century ago, Consolmagno says, while the most influential thinkers and leaders of the day were generally in favor of going wherever science might lead, there was one strong countercultural voice: “The Church. Because whether the science was right or wrong (it turns out the science was wrong), it was horribly immoral. The Church has always had the task of reminding people that just because you can do something doesn’t mean it’s a good idea.”

Science, he explains, was invented by the monks in the medieval universities, and was supported by those institutions. Then he says something that might seem counterintuitive today: “Most of the skill of doing science is skill that you learn in a theology class. It’s rationality, it’s trying to understand things you couldn’t understand—by using reason.”

Until the end of the 19th century, he explains, scientists were either noblemen, medical doctors, or the clergy. No one else had the education—or the free time—to go out and gather leaves, or sort and file.

“What do we call that work of sorting and filing?” he asks. “It’s called clerical work, because it was done by clerics. They were trained to record the data of births and deaths in their parish and they used that same skill to keep track of births and deaths of animals and plants, to keep track of the weather.” Knowing the longtime weather patterns was the result of record keeping by the parish priest. “Anyone who suggests that science and religion are opposed is trying to sell something that has nothing to do with science or religion,” he concludes.

The Scientist in the Pew

“I became a Jesuit after I’d been a scientist for 20 years,” Brother Guy says. When he “came clean” about his religious convictions, “I did wonder what my scientist friends would think. But the most common reaction was ‘let me tell you about the church I go to.'”

Citing findings by CARA (the Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate), Brother Guy says, “People in church on Sunday tend to be better educated than the general population.

As a result, they’re more likely to be scientists, doctors, and engineers. If you want to find the atheist on campus, you don’t go to the astronomy department.” Consolmagno urges Catholics to cherish science as part of their birthright. He says, “Science is a gift of God to the Church. To try to take it away from religious people deeply damages science because you’re cutting it off from the majority of the human race, who might otherwise be great scientists. And any religious person who is afraid of science, first, has no faith in their faith, and second, they’re losing their very heritage, what our Mother Church has given us.“

The Big Bang Theory: The Other Side

In his talks, Brother Guy often amazes audiences by telling them that the Big Bang theory—that the universe is expanding from an original, single mass—was actually formed and named by a Belgian priest, Georges Lemaître. He reviewed the theories of Albert Einstein and realized that the universe must be expanding, and therefore must have once been condensed. Lemaître told Einstein, “Your calculations are correct, but your physics is atrocious.” At first, Einstein himself ridiculed both the priest and the theory; later, he came to share Lemaîtres views, and the two became lifelong friends.

In a series for the BBC on how the universe will end, A Brief History of the End of Everything, Consolmagno offered a bookend of sorts for Lema√Ætre. He covered some of the most cutting-edge astrophysicists’ theories, but as a Jesuit, Consolmagno sees another dimension.

He says: “The science of the end of the universe is very different from the science of the beginning. We have data from the past; we have no data from the future. So everything is a wild guess. It’s an extrapolation. Everything that we’ve thought of is probably wildly wrong in some way.”

Like the Virgin Mary (in Luke 2:19), he says, we are given lots of wonderful things to ponder in our hearts. “The important thing—in science or religion—is never to stop because you think you have the answer. You never have the answer. If you think you understand the Trinity or quantum physics, you’re wrong.

“We realize in a beautiful way that all the simple answers don’t work.” If we take the Gospel account of the Resurrection at face value, Brother Guy says, “then that means that this body actually matters.” He strikes an ecological note, true not only to the Franciscan spirit, but to everyone, including this Jesuit: “What I do with this body matters. This physical universe matters. What we do in the universe matters. You can’t say it’s OK to trash the planet because we’re going to go off to heaven somewhere else. You can’t say it’s all right for me to abuse someone because God will save their soul later. It’s frightening, because it means it matters. And it’s reassuring, because it means it matters to God.”