Author Greg Tobin talks about the pope’s lasting impact.

Greg Tobin had an idea. When younger Catholics hear of Pope John XXIII, they might think of history’s Second Vatican Council, or perhaps they’ve heard vaguely of “the friendly pope.” Tobin wanted to interpret this man’s life for readers today. A book editor, author, and Church expert for many years, Tobin is vice president for university advancement at Seton Hall University.

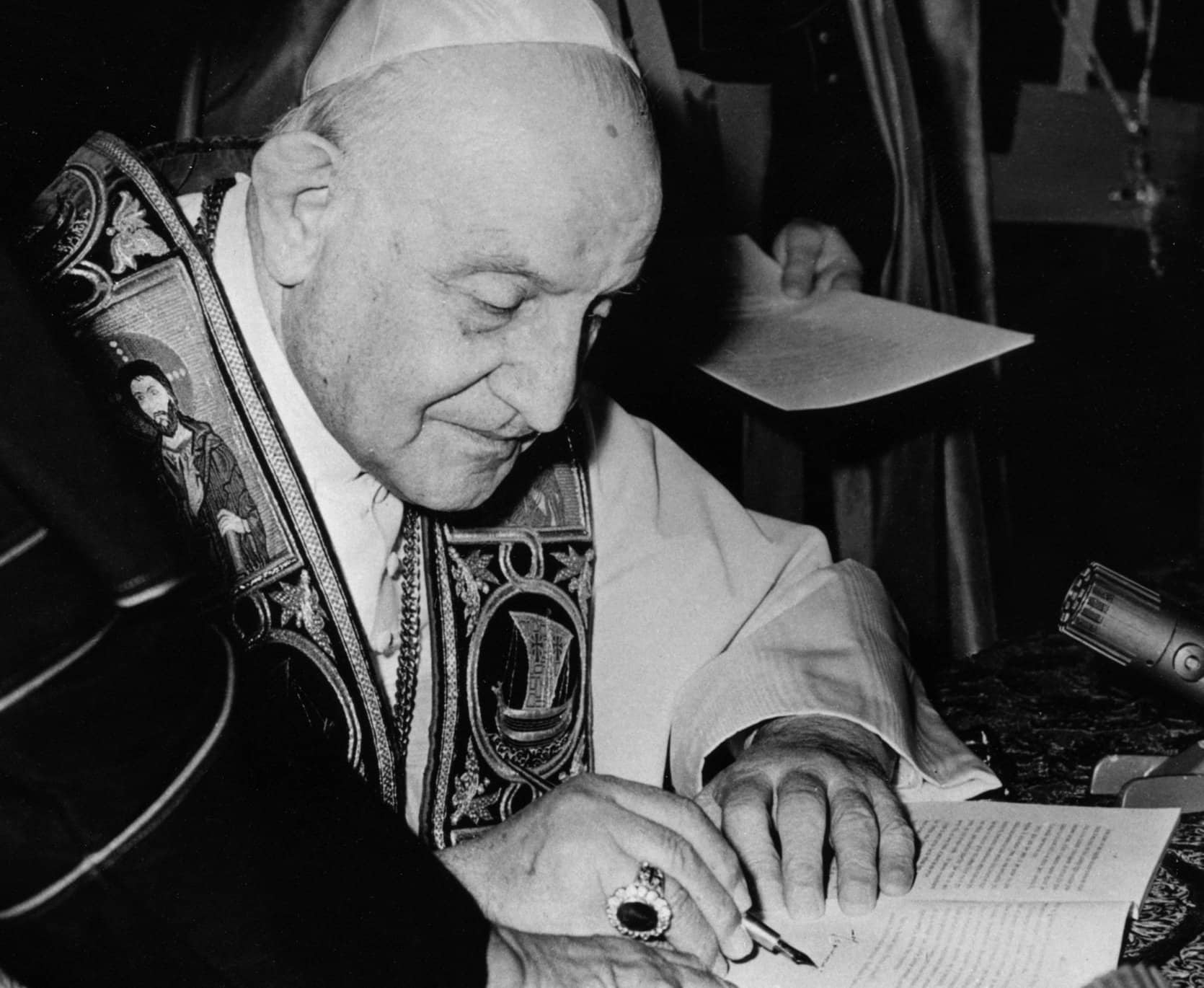

He wrote The Good Pope: The Making of a Saint and the Remaking of the Church (HarperOne). St. Anthony Messenger interviewed Tobin about a particular aspect of the pope’s life that changed the way the Church was seen by the whole world. Decades ago, newspaper headlines and magazine covers heralded a message of peace, “Pacem in Terris” (“Peace on Earth”), the final encyclical of this dying pope. It was addressed not only to the clergy and the faithful, but “to all men of good will.” People of good will around the world read it with interest—and with hope. His message of peace—specifically against nuclear weapons—gnaws at modern consciousness.

A Peace Plea from the ‘Pope of the World’

Tobin is certain that Pope John XXIII “has a message for us in our contemporary world.” Pope John’s background both as a soldier and as a veteran diplomat throughout World War II gave the pope keen insight and feeling for the theme of this encyclical, one which he knew would be his last, as he was dying of cancer, only five years into his papacy.

Tobin sketches the scenario. “Pope John was elected at the height—or the depth—of the Cold War, the terrifying nuclear standoff between East and West. That influenced his pontificate, and he had a great influence on world affairs during that time. He was conscious of his position of moral authority, and he wanted to be certain that he had as strong an influence on the drive for peace and reconciliation in the world as he could. So he conceived of this statement, this encyclical, with that in mind, I think. It sealed his identity as the pope of the world in a different way than any pope had been to that point. He became a model for the popes who would follow.”

Prior to John XXIII’s papacy, Tobin explains, “the Church had been largely in a defensive mode in the world. It had been under attack, persecution. It was very inward-looking in many ways, and John wanted to change that. He wanted to update many of the outward practices of the Church, and he wanted to open up the Church to the world so the world could look in and know what Catholics were about.

And there’s no more powerful or central message than that of peace. This encyclical really captured that in a way that was very conscious and deliberate on his part. It really had a very strong, immediate, powerful influence in the world.”

In Tobin’s book The Good Pope, he offers some backstory on the historic letter, which the pope conceived, Tobin says, during the 1962 Cuban missile crisis, when nuclear war seemed imminent. Pope John XXIII, through intermediaries, actually encouraged Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev to continue negotiations with the United States at this perilous time. He even sent an advance draft of “Peace on Earth” to the Soviet leader, possibly underlining the passages on arms proliferation and nuclear weapons. That alone earns the papal letter a place in world history.

At the time of its issuance, the US State Department, writes Tobin, broke a “precedent of silence toward papal encyclicals,” praising the encyclical. Positive response came from quarters as diverse as the Soviet news agency, the United Nations, and the National Council of Christians and Jews. Time magazine called it “one of the most profound and significant documents of our age.”

“It changed the conversation,” Tobin writes. “[The pope] engaged the world in gentle, impassioned, fatherly dialogue, understandable to superpowers and peasants alike.”

A Surprising Vatican Council

Of course, “Peace on Earth” is by no means the only mark Pope John XXIII left on the Church. Four years into his papacy, this former diplomat engaged the Church in a dialogue of renewal through the historic Second Vatican Council (1962–65). Together with this encyclical, it was the great—and unpredicted—achievement of his papacy.

Pope John invited observers of almost every religious tradition to attend (and he gave them good seats, Tobin reports). Pope John XXIII was a genuine optimist, says Tobin. He had a deep inward spiritual focus himself and, looking outward, he was focused on “building, reforming, shaping a Church that was defined through peace, spirituality, and a connection with God.” All this, Tobin says, “despite opposition that he faced within the Vatican to the idea of a council.”

Tobin recalls that “John XXIII, after the opening ceremonies, did not appear on the floor of the council, but monitored it from his apartment.” Why? Tobin says, “He didn’t want to appear to be forcing anything or favoring anything in the debates—and there were very hot debates. The council had opened with a big bang when the majority of the bishops rejected the agenda and a number of the draft documents out of hand and said, ‘No, we want to start from scratch—and really have some debate and discussion.’ That was not an easy situation, and it shocked the traditionalists deeply after all the hard work they had done.

“John had a vision for the council,” Tobin says, “but I don’t think he wanted to force it on anybody. He allowed things to develop in a way that ultimately put the direction of the council on the path he had hoped for from the beginning.” It was to be a pastoral council. It would not focus so much on doctrine as on the way the Church was to be present in the world.

Only on one issue did John enter directly into the proceedings of a council whose end he would not live to see. The solution, Tobin reports, was to pair Italian Cardinal Alfredo Ottaviani and the more liberal German Cardinal Augustin Bea to cochair the rewrite of the stalled schema on divine revelation, a teaching on how God makes the divine will known to people.

Delineating a Catholic understanding of both Scripture and tradition, it represents some of the council’s most important work. Tobin, together with other chroniclers of the council, asserts that this appointment of two squabbling prelates changed the course not only of that committee’s document, but of the entire council. The diplomat-pope had worked behind the scenes.

‘Vicar of Christ’

So what would Pope John XXIII think about the situation of the Catholic Church in today’s world? Tobin reflects, “His optimism would come into play if he were here to witness what’s going on within the Church, the various scandals, difficulties, and persecutions the Church faces in some parts of the world. He would very urgently call us to prayer in the way that Pope Francis has done.

“When it comes to facing the scandals, I think John would do it directly and gently. In his heart, he would be angry as well as sad at the causes of the scandals. This is going out on a limb, but I believe he was capable of absorbing things like this in the way that Christ did—taking on the sins of the world. . . .

“John XXIII was the Vicar of Christ and he had that capacity as well. He could just take a lot in and keep moving forward. He would keep a smile on his face and a prayer in his heart. I would say that Pope John had an extremely high emotional IQ.”