The Archdiocese of Atlanta now owns 50 percent of Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind. That’s like saying your local parish just found a Picasso in the cellar.

The Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, the Oscar-winning film it’s based on, and souvenirs such as dolls and collector dishes that carry images of Scarlett O’Hara and Tara, her plantation home, half of it all now belongs to the archdiocese, thanks to a bequest from Joseph Mitchell, one of the author’s nephews.

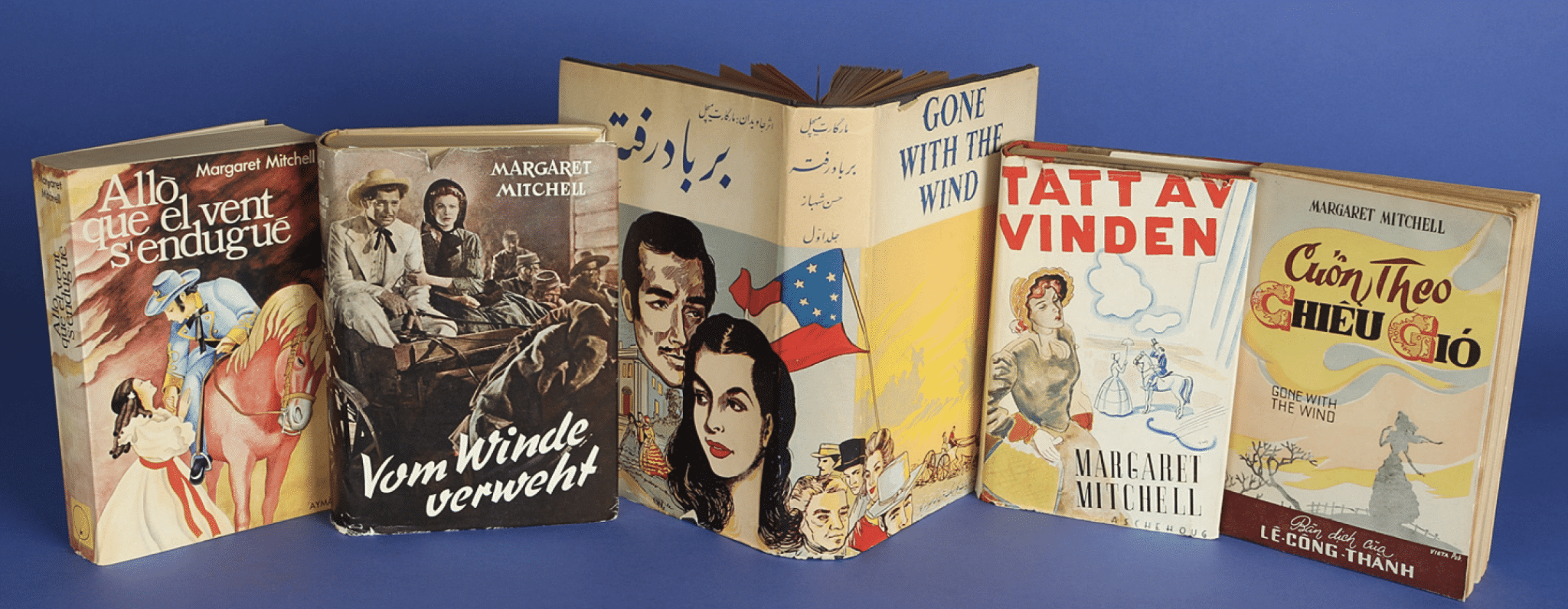

The legacy might seem ironic at first glance. Mitchell, an Atlanta native who was raised Catholic and left the Church to become an Episcopalian. A more penetrating examination, however, uncovers deep roots in the faith she inherited from her parents, roots that twine throughout Gone with the Wind, which has sold more than 30 million copies since its 1936 debut. It is the epic story of an Irish Catholic plantation family in Georgia during and after the Civil War, particularly of Scarlett, the rebellious, eldest daughter.

Bryan Giemza, who teaches American literature at Randolph-Macon College in Ashland, Virginia, told St. Anthony Messenger that “the key to understanding Mitchell is to remember that she was an Irish Catholic [with an] emphasis on both ‘Irish’ and ‘Catholic.’ Irish Catholics know how all-absorbing that identity can be.”

In an interview for this article, Darden Pyron, author of Southern Daughter: The Life of Margaret Mitchell, concurred, saying that her Catholic upbringing sprang from “an intense Irish-Catholic background. [It was] way down deep” in her. He compared Catholics in Georgia to another outcast group.

“Southern Catholics were like Jews: in the South but not of the South,” he says. “That sense of separateness is a classic definition of what makes for creativity.”

Giemza, who recently published Irish Catholic Writers and the Invention of the American South, which includes a chapter on Mitchell, says that her dilemma as she grew up “was a familiar one for southern Catholics: Irish Catholics were seen as ‘unsouthern,’ so there was potentially some social pressure to downplay Catholicism, or perhaps to go the other way and to wear it plainly. Members of her family took both courses. As is often true of Irish Catholics, she might leave the Church and yet find that the Church never left her.”

Mitchell’s Faith Was No Fiction

Evidence of Mitchell’s faith is scattered throughout Gone with the Wind. For instance, an early scene in the novel tells how Scarlett’s mother, after praying for her family, would say the rosary.

“Once you start looking for Catholicism in the novel, ” Giemza notes, “you realize that it’s not just present, it’s a living presence. The family prayers and rosaries aren’t incidental details. Mitchell’s mother had a second cousin who entered the Sisters of Mercy at St. Vincent’s Convent in Savannah in 1883. [The cousin] became Sister Mary Melanie. It’s quite likely that she furnished the model for Melanie Hamilton,” a key character in the novel who provides a virtuous counterpoint to Scarlett’s misbehavior.

To Pyron, “in some ways, the moral structure of Gone with the Wind is very Catholic. It uses a negative model. It has a clear kind of morality and immorality. Mitchell insisted that the real heroine was Melanie, not Scarlett.”

At the heart of the novel, however, stands Scarlett, a major figure in 20th-century American fiction, but one who is not often thought of as being a Catholic. However, Mitchell makes it very clear that her heroine had a religious upbringing that played a role throughout her life.

Notes Giemza, “Scarlett remains a reflexive Catholic by her own admission she’s not a very good or worthy one, but one who admires faith in others and who resorts to prayer constantly throughout the novel. She has a Catholic imagination, and so she sees her mother always in terms of the Holy Mother. Scarlett prays all the time, but her prayers are uniformly devoted to her own desires.”

Mixed Reviews

When the book debuted in 1936, Catholic reaction varied. A reviewer for Commonweal magazine lauded it as a “magnificently vital novel” that offered a “panorama of evocative literary magic unequaled in American historical fiction. For Catholic readers it has a special meaning, a sorrowful one. . . . For it shows us how the O’Hara family . . . made shipwreck of its religious life.”

Pro and con assessments appeared in America, a weekly magazine published by the Jesuits. “One priest objected to the book’s use in a high school classroom,” Giemza says, “and another suggested that it might be ‘objectionable in parts.'”

In response, Msgr. James H. Murphy of Ellicottville, New York, penned a letter to the editor to defend the novel. He called Ellen O’Hara, Scarlett’s mother, “the most beautiful character in the book . . . an embodiment of the valiant women of Scripture. ” He lauded the novel for “conclusively prov[ing] that true religion is its own reward and, in time of calamity, man’s only solace.”

In a private letter, Mitchell thanked Murphy for his defense. “Your answer made me very happy, ” she wrote. “A number of times the character of Scarlett O’Hara has been attacked, and I have been accused of portraying ‘a bad woman’ who by her wickedness cast into disrepute virtuous Southern ladies.”

Such criticism caused Mitchell to feel downhearted because she had “tried so hard to portray the wonderful women of the old South,” including those “stouthearted matrons who knew right from wrong” and “refused to tolerate Scarlett.” The novelist affirmed that Scarlett was someone whose misdeeds were meant to inspire the opposite behavior.

God and Miss Scarlett

As far from virtue as Scarlett wanders in the book, the story is filled with moments that confirm her lingering faith.

“Toward the end of the novel,” Giemza says, “when Scarlett clasps Melanie’s hand, ‘a flood of warm gratitude to God swept over her and, for the first time since her childhood, she said a humble, unselfish prayer.’ In that prayer, she recognizes how unworthy she is. She has earlier acknowledged that her sins might be the cause of her own downfalls and even ruinous to others.”

Mitchell also contrasts Scarlett and her mother, Ellen, writing that the former “was driven by a conscience which, though long suppressed, could still rise up, an active Catholic conscience. ‘Confess your sins and do penance for them in sorrow and contrition,’ Ellen had told her a hundred times and . . . Ellen’s religious training came back and gripped her.”

There has been endless speculation as to how much Scarlett is a reflection of Mitchell. Their common Catholic faith is one example of what they share.

“Scarlett’s struggle with faith is more than skin-deep. I suspect this was the case for her author-creator, too,” Giemza says. “What Scarlett admired in her mother was her absolute certitude. Finding her own faith to be complicated and wavering, Mitchell, at the very least, seemed to recognize the preciousness of the gift of faith.

“Understanding the Irish strain of Catholicism helps us to comprehend Margaret Mitchell,” Giemza continues. “Accounts of her life reflect her generosity and dedication to charity and caring for others. In fact, she gave so much of herself over to fans of her book that her writing productivity came to an abrupt halt. Though it may be a loss to literary posterity, it says much about a certain kind of Catholic conscience.”

Legacy Lives On

Three-quarters of a century after the book’s debut and 64 years since Mitchell’s death, half of the income generated by Gone with the Wind, which sells as many as 50,000 copies annually, now rests in the hands of the Catholic Church.

What would the author have thought of that?

“My instinct,” says Giemza, “is that, however strained her relationship to the Church might have been, she was a genuine ecumenicist. Even if she was critical of the Church, I don’t see any evidence that her distance from it was based in ill will.

“On the contrary, if we look at her life and literature, she found much to admire in the faithful. I expect that Mitchell would care that the proceeds from her work reap a good harvest.”

Darden Pyron, Mitchell’s biographer, agrees. “She wouldn’t be offended. From my judgment of her, she had no real ill feelings about the Church. She would probably have a very wry smile about it.”

Margaret Mitchell’s Gift

Firm Faith Led a nephew of author Margaret Mitchell to donate half of the rights to her celebrated novel, Gone with the Wind, to the Archdiocese of Atlanta.

“Joseph Mitchell, who made the bequest, was a longtime parishioner at the Cathedral of Christ the King,” says Deacon Steven Swope, who has taken on the task of overseeing the legacy, estimated to be worth between $16 million and $18 million. Mitchell asked that “special consideration be given to the Cathedral and to the poor, with the balance of the funds to be used for general religious purposes.” Indeed, plans are already under way to help finance the cathedral building fund and Catholic Charities.

Swope, who retired recently as associate director of diaconate formation in the archdiocese, will oversee the bequest. As a longtime admirer of the book and the film, the deacon believes that elements of the author’s faith can be detected in both works.

For example, he cites “the great dignity that she gave to the key black characters. Mammy [a slave] is portrayed as being wiser than her masters. And Big Sam [another slave] exhibits great kindness and compassion. These two show love, wisdom, and compassion in the face of their persecution. That hearkens back to the model of Christ.”

The reaction of Catholics in the Atlanta Archdiocese to the gift “has been one of awe and gratitude,” Swope notes. “The size of the bequest and the generosity of Joseph Mitchell are truly wonderful. The fact that the archdiocese now owns a 50-percent share in the rights to the novel is astounding.”

Swope expects the archdiocese’s share of Gone with the Wind to produce between $100,000 and $200,000 annually for the next 20 years. The copyright to the novel expires in 2031.

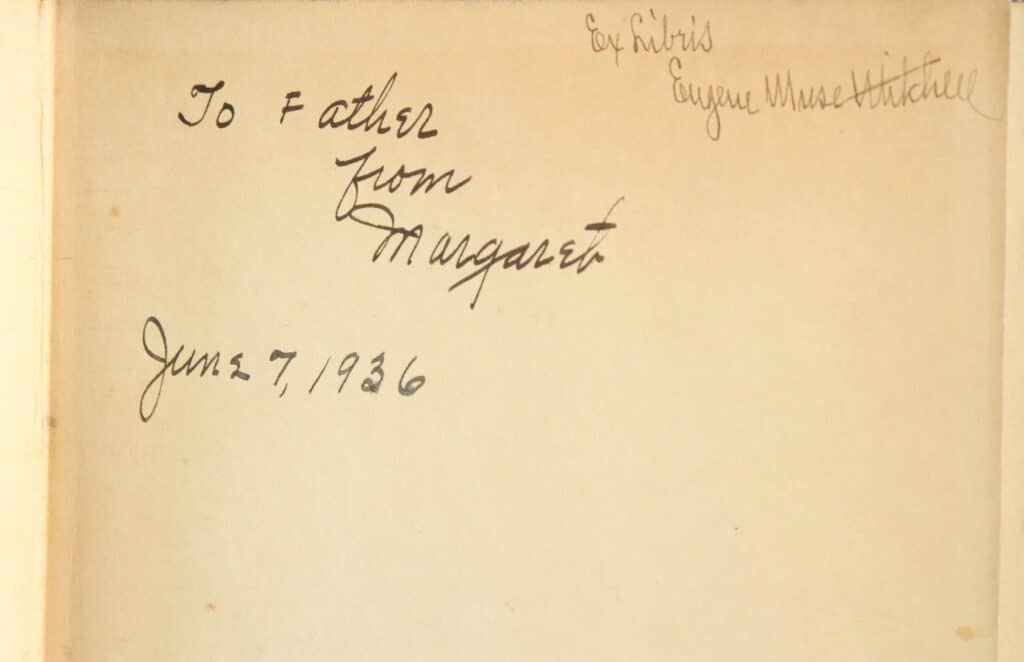

In addition to the rights to and income from Gone with the Wind, the archdiocese was given “tangible items that belonged to Margaret Mitchell,” ranging from furniture to autographed first editions of another Catholic novelist: southern writer Flannery O’Connor. “They are being held in a safe place for later display,” Swope says.

The deacon calls Mitchell’s bequest “one that will continue to provide for the poor and the people of God.”