When you think about the purpose of the public schools in our country, what comes to mind?

Beyond the obvious goal of providing an education on a variety of subjects to prepare the new generation for the next steps in life, there are athletics, school lunches, and extracurricular activities. We also hope or expect our public schools to instill model citizen behavior in students and encourage qualities such as intellectual curiosity, innovation, ethics, and creativity.

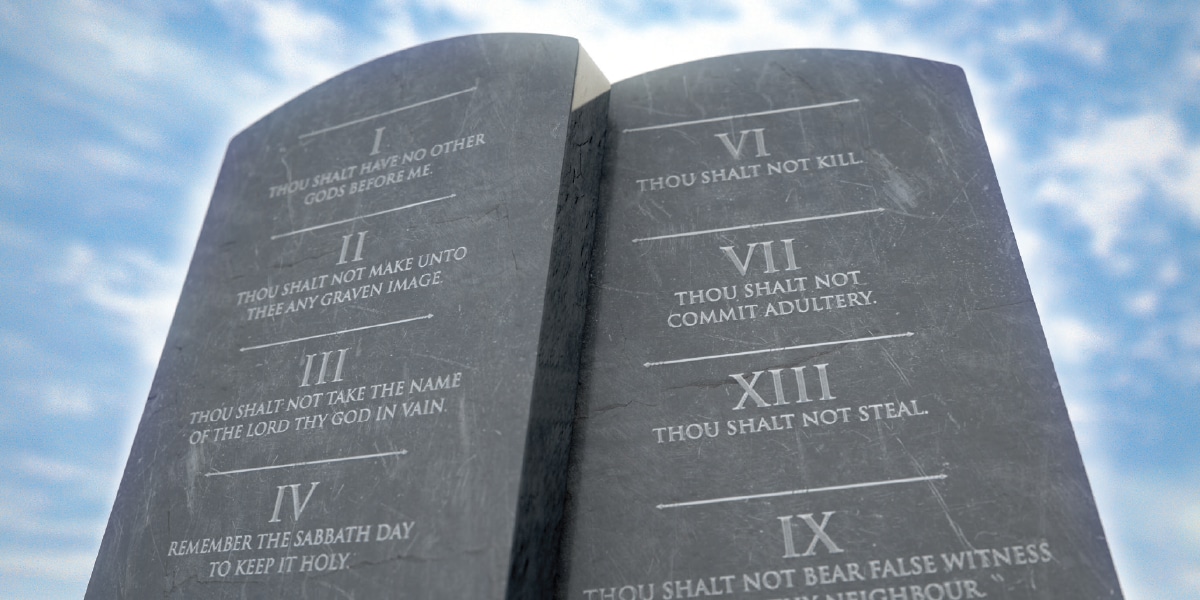

Missing from the list is the promotion of any particular religious belief. But a law passed recently in Louisiana seeks to change that by making it mandatory for public schools to display a poster or framed copy of the Ten Commandments in every classroom, school library, and lunchroom, beginning with the 2025 academic year. The move created an instant swirl of controversy and has led to many frank discussions on the very nature of our nation’s schools, religious freedom, and free speech.

Freedom of—and from—Religion

To be sure, Judeo-Christian morality played a major role in the formation of our country, as all 250 signers of the Constitution were Christians of some stripe. It’s also true that the phrase separation of church and state appears nowhere in the Constitution. So why is it problematic for public schools in Louisiana to display the Ten Commandments?

It all comes back to the First Amendment, freedom of religion, and the Establishment Clause, which states, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” This clause, in essence, safeguards government from religious special interests while also protecting religious groups from political interference. There was—and is—a Church of England, but there would be no Church of the United States.

Still, personal religious observance and prayer groups are not prohibited in public schools. Coaches can say prayers after games, if they choose to, for example. But placing the Ten Commandments in every classroom is not a personal choice being made by students, teachers, or coaches, but rather politicians with agendas and constituents to please. Many of those who pushed Louisiana House Bill 71 through legislation also espouse dangerous notions of Christian nationalism (see Mark P. Shea’s article on page 20 for more).

Some might think that the notion of displaying the Ten Commandments in schools would be welcomed enthusiastically by the American Jewish community. Not so. An article for the Jewish Chronicle (“Jewish Groups Protest Louisiana Law Requiring the Ten Commandments in All Classrooms,” by Faygie Holt), quoted Aaron Bloch, the director of Jewish Multicultural Affairs at the Jewish Federation of New Orleans, who said: “At a time when Louisiana faces significant educational challenges, ranking 47th nationally, this legislation distracts from addressing crucial educational needs. Furthermore, it risks excluding students of various faiths or those who adhere to no faith.”

Supporters point to the Ten Commandments as reflecting universally held beliefs and truths and argue that, by placing them in classrooms, there is no conflict of interest since they are so intertwined with the ethical foundations of our society. But they fail to understand that freedom of religion in the First Amendment isn’t only for the largest religious groups, but also the minorities. In fact, it’s really there to protect smaller groups from being subjected to influence and control by the majority.

Parents who are among to the approximately 3 million Buddhists and 2.5 million Hindus living in the United States shouldn’t have to worry about their children being indoctrinated in public schools any more than Christian parents. Would Christian parents feel comfortable with another religion’s text being displayed in public school classrooms?