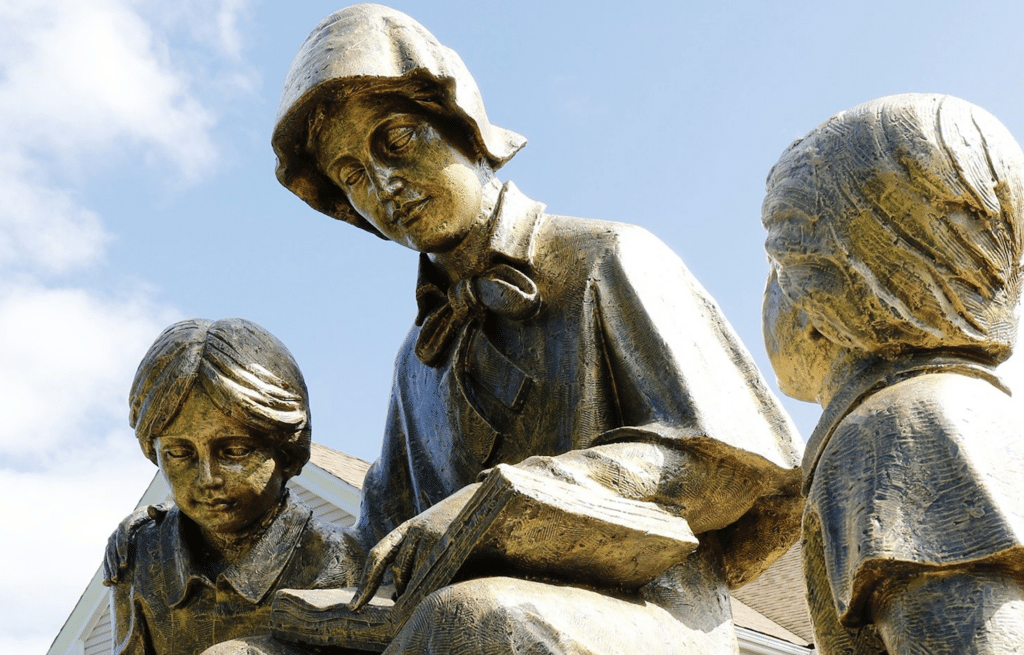

Daughter, wife, mother, widow, friend—all of these describe this first American-born saint.

Now that the word “saint ” has been attached to Elizabeth Seton, some Catholics might be conjuring up a gauzy image of an ethereal woman. But this country’s first native-born saint shatters that stereotype. Elizabeth was nothing if not intensely human, her holiness rooted in her wholeness.

In the details of her life as daughter, wife, mother, widow and friend, we discover a well-rounded woman who knew how to love deeply and was always a person for others, even in the midst of trying situations.

Elizabeth Ann Seton: Selfless Spirit

Elizabeth was born in New York City on August 28, 1774, to Richard Bayley and Catherine Charlton Bayley, who died when Elizabeth was three.

One of three daughters, Elizabeth, or “your Betty ” as she refers to herself in letters to her father, admired the work of her physician father. Dr. Bayley attended to immigrants as they disembarked from ships onto Staten Island, and cared for New Yorkers when yellow fever swept through the city, killing 700 in four months in 1795.

Dr. Bayley’s selflessness was inherited by his daughter. As a young mother and wife, Elizabeth was among the orginal members of the Society for the Relief of Poor Widows with Small Children, founded in 1797 by Isabella Marshall Graham in New York. Elizabeth and her friends Catherine Dupleix and Eliza Sadler paid $3 a year in dues to help support the work.

As treasurer, it fell to Elizabeth to visit homes to assess the families’ situations. In a letter to Julia Scott, she tells of her own two boys “who were taken sick this morning with symptoms of the measles which are very prevalent in our city. ” She thanks Julia for the money to aid the widows.

Even as Elizabeth deals with her own sons’ illnesses, she comments that “indeed I have many times this winter called at a dozen homes in one morning for a less sum than that you sent, for you may be sure these measles cause wants and sorrows which the society cannot even half supply and in many families the small pox and measles have immediately succeeded each other. “

Well-Rounded Life

Serving others—that’s what saints do. But during the same years that she was attending to widows and children, Elizabeth was also living the life of a socialite, as a member of Trinity Episcopal Church, the church for New York’s upper class, and a devotee of the theater, popular novels and music.

In a letter to Julia, Elizabeth teases that angels must exist because when coming out of the theater with her sister “we came out in a violent thunder gust and got in our hack with carriages before and behind and aside—the coachmen quarrelling. First one wheel would crack, then another…but my Guardian Angel landed me safe in Wall Street [where she and her young family lived] without one single hysteric. “

And while we know she immersed herself in religious books, like A Commentary on the Book of Psalms, which she received from her beloved Episcopalian minister, Rev. John Henry Hobart, she also notes in a letter to Eliza Sadler during the same years that she loved The Children of the Abbey, a gothic novel that was a hit in America at the time. “Indeed, ” she wrote, “I could not name more than half a dozen I would rather read. “

Elizabeth was an accomplished pianist, while her husband, William Seton, who brought the first Stradivarius violin to America, relaxed in the evening by playing for and with his young wife.

If music linked them while they were together, Elizabeth’s letters kept them in touch while her husband traveled on business for his father’s merchant import firm, the prestigious Seton, Maitland and Company. Less than six months after their marriage in 1794—when she was 19 and he 25—she sent him this message in a letter: “Ah, my dearest husband, how useless was your charge that I should ‘think of you.’ That I never cease to do for one moment, and my watery eyes bear witness to the effect those thoughts have, for every time you are mentioned they prove that I am a poor little weak woman. “

If caring deeply for William made her “weak ” in her own eyes, that label fell away quickly as she was challenged in her early years of marriage to draw upon an inner strength to see her through crises that might have driven truly “weak ” women to despair.

Rapidly Expanding Family

Childbirth was always risky in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, and Elizabeth narrowly escaped death delivering her third child, Richard, in 1798. “My illness was so severe that both mother and child were some hours in a very doubtful situation, ” she writes to Julia. Elizabeth had just enough energy to look down from her bed to watch as her father, on his knees, “blew the breath of life ” into Richard’s lungs and “by his skill and care ” restored the baby.

No sooner had she recovered from childbirth than she and William took over the care of his six younger siblings, since he was now responsible for them after the elder Seton’s death. (William’s father had been widowed twice.) Imagine the adjustment for Elizabeth, “who so dearly loves the quiet and a small family ” in taking on these duties for several years with the help of William’s sister, Rebecca.

In addition to caring for her own three children, one a newborn, Elizabeth Seton became a mother to the six newly orphaned Setons, ages seven to 17, caring for their physical needs and teaching them to read, write and sew. At times the house emptied out while the older Seton children were away at school, but activity picked up when they came home for holidays.

Even though she had help from Rebecca and a housekeeper, Elizabeth must have felt she had plunged into the middle of a whirlwind of activity and neediness. Having moved into a larger home to accommodate the Seton clan, she writes to Julia, “I cannot help longing again for the rest I have never known but in Wall Street. “

That coveted rest would elude her as she helped William with the family business. “My William has kept me constantly employed in copying his letters and assisting him to arrange his papers, for he has not friend or confidante on earth but his little wife. “

Profound Losses

The business took its toll on her husband’s health, already weakened by a youthful bout with tuberculosis. With the family business slipping, along with William’s health, the couple arranged a sea voyage to Italy in 1803.

Turning over the care of their four youngest, including baby Rebecca, to relatives, Elizabeth and William took with them eight-year-old Anna Maria (nicknamed “Annina “), and headed off to Leghorn, where they would be welcomed by Antonio Filicchi and family, at whose counting house William had interned.

As their ship entered the port at Leghorn, the Setons were met by Italian officials who denied them entry, since their ship had departed from the port of New York, where yellow fever was raging. Despite the protests of the Filicchis, the Setons were sent to a lazaretto for quarantine, “an immense prison bolted and barred. ” There William lay “on the old bricks without fire, shivering and groaning, lifting his dim and sorrowful eyes, with a fixed gaze in my face while his tears ran on his pillow without a word. “

Although they were eventually able to leave the quarantine and visit Pisa for a few days, it was to no avail. As Elizabeth’s husband sobbed, “My dear wife and little ones, ” he died in her arms, with their Annina nearby. By Italian law, he was buried within 24 hours.

Elizabeth describes the ordeal in a journal she kept for William’s sister and her “soul sister, ” Rebecca: “Oh, oh, oh what a day. Close his eyes, lay him out, ride a journey, be obliged to see a dozen people in my room till night—and at night crowded with the whole sense of my situation—O my Father, and my God! “

William was not the first or the last of several loved ones she would hold as they journeyed into the next life. Two years before William’s death, her father had suddenly taken ill. The previous day, he had called Elizabeth out “to observe the different shades of the sun on the clover field before the door and repeatedly exclaimed, ‘In my life I never saw anything so beautiful.’ “

The next day, as he came in from the wharf, his legs weakened and he turned delirious. The night he died he continually cried out to her phrases like “all the horrors are coming, my child, I feel them all, ” before “he became apparently perfectly easy, put his hand in mine, turned on his side and sobbed out the last of life without the smallest struggle, groan or appearance of pain. “

Losing her father, then her husband, was devastating—but even more wrenching, she would bury two daughters. Both of them died after she moved to Emmitsburg, Maryland, to open a school and found the Sisters of Charity. When her children were toddlers, Elizabeth had described how “my precious children stick to me like little burrs “; in their later years she would have given anything to keep them that close.

More Heartache

Already bonded to Elizabeth after William’s death in Italy, Annina, as oldest, was her mother’s support during widowhood and her move from New York to her new life as religious “mother. ” After a failed romance, which Elizabeth nurtured her through, Annina helped with the young boarders in the school. What a shock for Elizabeth to one day notice Annina’s reddened cheeks, the telltale sign that, just as her beloved William had, she was being dragged down by tuberculosis.

Annina’s death at age 17 was a role reversal, the daughter comforting her mother: “When in death’s agony her quivering lips could with difficulty utter one word, feeling a tear fall on her face, she smiled and said with great effort laugh, Mother, Jesus at intervals as she could not put two words together. “

Annina’s death almost undid Elizabeth. Her family, friends and spiritual mentors feared for Elizabeth’s physical and spiritual health. But she bounced back, giving herself over to God, and feeling Annina’s presence in her life to help her go on.

When a few years later daughter Rebecca developed a tumor in her hip, which no doctors could cure, Elizabeth sat with her “nine weeks, night and day, ” holding Beck to ease her pain before she died at age 14.

A Mother’s Worry

Even as she was attending to her sick daughters, Elizabeth worried about her sons, William and Richard. Neither seemed suited for business, though she arranged for both to work in Italy with Antonio Filicchi, who remained her friend over the years after William’s death.

The life young Will aspired to caused her great worry: He wanted to join the United States Navy at a time when wars were raging off the shores of the States, and France and Italy were constantly in an uproar.

But before her death, Will had settled down, well established in the Navy, “more and more pleased with the choice of his profession which seems to us so extraordinary. ” Had she lived, Elizabeth would have been grandmother to his eight children.

Richard, Will’s younger brother, also spent some time with Antonio Filicchi. Filicchi’s letters assured Elizabeth that Richard was “very satisfactory, ” in response to Elizabeth’s concerns in her final years of life: “if my Richard does but do well is my greatest anxiety. ” Though neither son was much of a letter-writer, William had a better excuse since he was away at sea.

To Richard she writes: “You can have no idea of our anxiety to hear from you—six, seven, eight months without one line. ” He did make it home to see his mother before her death in 1821, then followed his brother into the Navy the next year as a captain’s clerk. A year later he died on ship while nursing the American consul to Liberia and was buried at sea.

Even as Elizabeth fretted over her sons, she found comfort in the companionship of her only remaining daughter, Catherine—variously nicknamed Kitty, Kate, Kit or Jos (her middle name was Josephine). In a note to her daughter on her birthday in 1819, Elizabeth wrote, “Whose birthday is this, my dear Savior? It is my darling one’s, my child’s, my friend’s, my only dear companion left of all you once gave with bounteous hand—the little relic of all my worldly bliss. “

As Elizabeth was nearing death, a huge concern was to prepare Catherine to face life without her mother. The Little Red Book of advice and spirituality she wrote for Catherine was her daughter’s keepsake for many years after Elizabeth’s death.

Keeping a promise they made to Elizabeth near her death, longtime friends Robert Goodloe Harper and Catherine Carroll Harper took Catherine into their home after Elizabeth died. Like her brother Richard, Catherine never married. She became a Sister of Mercy in 1846, devoting more than 40 years to working with prisoners in New York as Mother Mary Catherine.

Lifelong Friends

Although Catherine moved in with the Harpers, several offers to take in the soon-to-be-orphaned child came from relatives and friends, including Julia Scott. It was in letters to friends like Julia, Catherine Dupleix, Eliza Sadler and Antonio Filicchi that Elizabeth would share the ups and downs of her life, from early marriage until near death.

Julia and Elizabeth had much in common. Probably a family friend of the Bayleys in New York, Julia was about 10 years older than Elizabeth. After Julia’s husband died in 1798, a foreshadowing of Elizabeth’s own widowhood, she moved to Philadelphia, remaining a lifelong friend through her letters, sharing details of the joys and sorrows of daily life.

To Julia in 1801, Elizabeth writes about her father’s death: “The night before my father’s death Kit lay all night in a fever at my breast and Richard on his mattress at my feet vomiting violently.”

Once settled in Emmitsburg, she kept in touch with Catherine, writing, “Kitty is only less than an angel in looks and every qualification. Oh, Du√©, if you knew her and your little Beck as they are and could see them every day, you would say there is nothing like them.”

Still playful even as a religious sister, she writes Eliza Sadler that when the “echo” of news that Eliza had decided to go to France reached Emmitsburg, “Kit and I answered it with so many Ah’s and Oh’s—you would have been amused to hear us.”

Near the end of her life, Elizabeth continued to write Antonio, whom she sometimes called “my dearest Tonierlinno.” To him, she owed much. He and his wife, Amabilia, had helped bury William, and had provided a temporary home for her and Anna Maria.

It was Amabilia who had invited Elizabeth inside a Catholic church, where she was amazed by worshipers’ belief in the Real Presence in the Eucharist, a belief foreign to her experience as an Episcopalian. It was Antonio who taught her the Sign of the Cross.

During the young widow’s voyage back to the States, Antonio was with Elizabeth and Anna Maria. And it was he who encouraged Elizabeth to pursue the call to become Catholic, despite pressures back home from the Rev. Hobart and her Protestant friends.

Throughout her life, she would turn to him for financial support, but more importantly as an anchor for her Catholic faith.

Years later, now as a leader of a religious community, Elizabeth would remind him of the essential role he played in her spiritual life: “The first word I believe you ever said to me after the first salute was to trust all to him who fed the fowls of the air and made the lilies grow.”

As her health was failing in 1818, she penned this line to him: “Dearest Antonio, I may well say with my whole heart, ‘Thy will be done’—love and bless your little Sister and devoted, Seton.”

On January 4, 1821, at 46, Elizabeth died of the tuberculosis that had plagued her much of her life, especially in her last few years. Although she would have to wait to fulfill her desire to be with Antonio in eternity, she herself was finally one with her God, as she had wanted.

When Elizabeth died, she left more than a legacy of Catholic education and religious leadership; she left an imprint on the many family and friends to whom she had endeared herself. As Barbara McCormick and others have testified so often, that imprint has not dimmed over the nearly two centuries since her death.

In Elizabeth Seton, McCormick sees “a saint for the 21st century and all of the centuries to come”—for her strength, her courage, her faith and her humanity.

Read: The Nuns Are OK: Building a Sustainable Future for Women Religious

Elizabeth Ann Seton Elizabeth Ann Seton Elizabeth Ann Seton Elizabeth Ann Seton Elizabeth Ann Seton Elizabeth Ann Seton Elizabeth Ann Seton Elizabeth Ann Seton Elizabeth Ann Seton Elizabeth Ann Seton Elizabeth Ann Seton Elizabeth Ann Seton Elizabeth Ann Seton Elizabeth Ann Seton Elizabeth Ann Seton Elizabeth Ann Seton Elizabeth Ann Seton Elizabeth Ann Seton Elizabeth Ann Seton Elizabeth Ann Seton Elizabeth Ann Seton Elizabeth Ann Seton Elizabeth Ann Seton Elizabeth Ann Seton Elizabeth Ann Seton Elizabeth Ann Seton Elizabeth Ann Seton Elizabeth Ann Seton Elizabeth Ann Seton Elizabeth Ann Seton Elizabeth Ann Seton