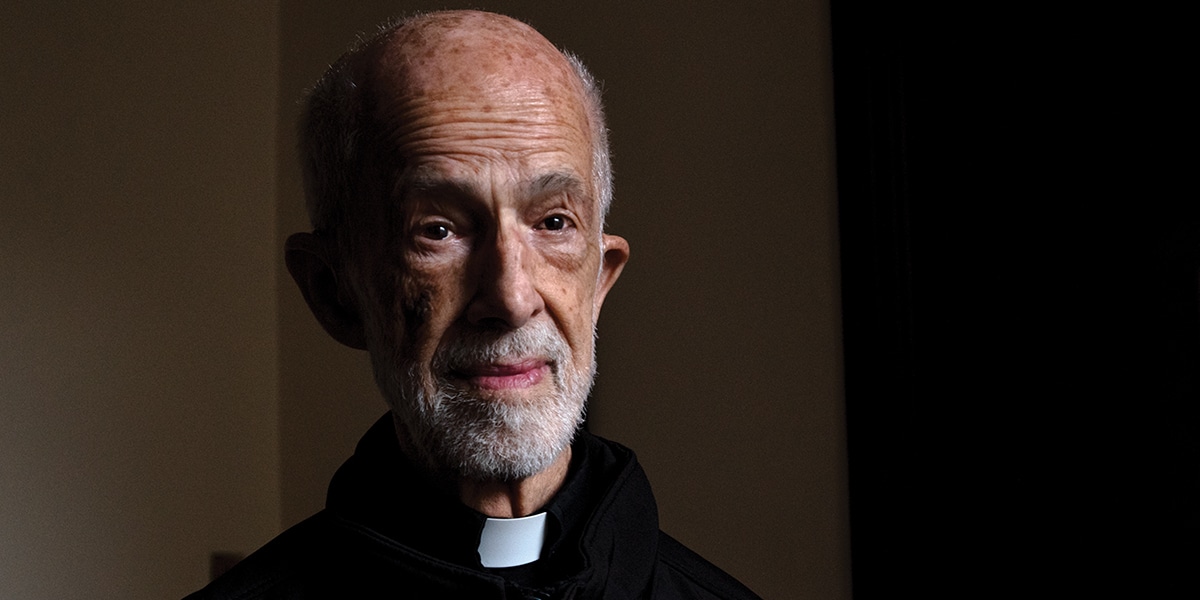

Filled with passion and energy, 85-year-old Father Ruskin Piedra works tirelessly to support and defend the immigrant community in his Brooklyn parish.

If there is glamour in being an immigration rights lawyer, it’s not evident in an eighth-floor waiting room in Lower Manhattan for those seeking authorization to stay in the United States. The nondescript room is set aside for immigrants from Brooklyn. It is half empty, with only a few dozen people waiting to be called this particular winter morning. Amid the conversational sounds of Chinese, Russian, and Spanish, the television set blares a speech from the president of the United States presented the night before, blaming immigrants for murders, rapes, and drug dealing.

“The president tries to paint the immigrants as vicious, violent criminals,” says a commentator on New York One, an all-news station.

Among this tiny composite of New York immigrants, no one appears to share the outrage, to be insulted, or, for that matter, to be paying much attention.

A priest strides in, dressed in full collar, accompanied by a Mexican couple and their college-age daughter. The priest, Redemptorist Father Ruskin Piedra, a wiry, diminutive octogenarian not much more than 5 feet tall, brings the family to the proper line. They get their ticket, and they wait. Father Piedra knows where to go. At the age of 85, he’s been doing this for decades, navigating the labyrinth of immigration bureaucracy for immigrants in Brooklyn as an officially recognized lawyer in the system.

“He is amazing,” says Eduardo, a Mexican immigrant who has been in Brooklyn for more than 20 years, and the husband/father of the family Father Piedra is accompanying this morning. “He’s working hard for the community. He is very friendly and responsive.”

Eduardo is a member of Our Lady of Perpetual Help Church in the Sunset Park neighborhood. It is a place spared much of the turmoil of Brooklyn gentrification, which has displaced tenants in favor of wealthy newcomers throughout the borough. The neighborhood remains in large part what it has always been, an immigrant enclave.

Eduardo is looking for a way to regularize his situation. His daughter Caroline, born in the United States and an American citizen, is a student at Brooklyn College. She is sponsoring her family, which includes Eduardo, her mother, and a younger brother.

The waiting room has the apparent urgency of a motor vehicle office. There is a studied blas é attitude among the clients and their advocates, many of whom have been here before. But for Eduardo, it could prove to be the most important interview of his life.

“What does this mean?” he is asked.

“Everything,” he says. He came to the United States when he was 18. He is now 46. Getting legal authorization would allow him to see his family in Mexico. A full generation has come and gone, and he can only communicate electronically. He would like to see his mother and father before they die. Time is not a friend.

A Stalwart of Support

In his way, Eduardo stands in a long Brooklyn Catholic tradition. For 126 years, Our Lady of Perpetual Help Parish has served them all: Irish, Germans, even Norwegians, and, in the past few decades, a growing group of Chinese. Mass at the parish is now celebrated in English, Spanish, and Chinese. Since the 1990s, Father Piedra, in his tiny office at what is called the St. Juan Neumann Center overlooking the parochial school gym, has been advocating for immigrants. He formally established the center in 2003.

While not a full-fledged lawyer, he has credentials, earned via classes on immigration law and the federal system, to advocate in court for those seeking legal status. In much of the outside world, the status of priest may have lost much of its social impact, but Father Piedra says the Church connection is a help to his cases.

“They pay a lot of attention to Church-related evidence,” says the priest about those charged with carrying out the nation’s immigration laws. “This is a Church with a history. We didn’t just put up a sign.”

Church documents, such as baptismal and marriage certificates, can be used as evidence of an immigrant’s residence in the country. They can all be helpful, even in this era of a crackdown on entering the country. The US Citizenship and Immigration Service’s official mission statement once described its role as fulfilling the ideal of America’s position as “a nation of immigrants.” It no longer uses that language—now it’s about enforcing the law.

Rooted in Service

It’s another series of obstacles for Father Piedra, who speaks in the characteristic gravelly tone of a native New Yorker. Born in what was then called Spanish Harlem, now East Harlem, he has lived the immigrant experience. He speaks little about himself, and much about his immigrant clients. But when he talks, he offers hints about how this passion developed.

His family came to New York from Cuba in 1918, to a nation less prosperous but more open to newcomers. (Laws severely restricting immigration would be enacted six years later during another wave of anti-immigrant sentiment that swept the country.) His Spanish first name is Sabino, and his parents, new to the country, picked out Ruskin from a newspaper article, thinking it sounded authoritatively American, he says. He is one of eight siblings, half, like him, born in the United States, the other half in Cuba.

As a result, he speaks fluent Spanish and has an innate awareness of Latino culture, particularly that from the Caribbean. He was an altar boy at St. Cecilia Church in Manhattan and was inspired to enter the seminary when, on a family visit to Cuba, he observed a large priest leading a congregation in the rosary, bundled up in wool vestments and sweating in the tropical heat. “Wow, what a sacrifice,” the future priest thought. He wanted to share in that kind of dedication.

Father Piedra’s vocation, therefore, grew out of his personal experience, both growing up in immigrant Spanish Harlem with his Cuban family, and later through his early priesthood work in missions in Puerto Rico and Florida. Since 1962, he has been working with immigrants, first assisting those fleeing Castro’s Cuba, and years later earning his advocate credentials in 1998.

Five years later, he established the St. Juan Neumann Center, named for the Redemptorist founder and bishop from Bohemia in central Europe, John Neumann, who came to the United States in 1833 as a seminarian versed in 11 languages and ready to minister to a burgeoning immigrant Catholic population in the New World. The story goes that Neumann learned his final language, Spanish, from a Mexican boat worker he met on the ship over to the United States. He later became the archbishop of Philadelphia.

Neumann’s immigrant legacy earned him accolades and, eventually, canonization. But Father Piedra, who follows that legacy, knows that immigration has emerged as a volatile issue, even among those Catholics who count themselves as descendants of the immigrants served by the first US Redemptorists.

“You can’t let everyone in,” Father Piedra hears from his network of friends outside the immigrant community, nurtured through his years as a retreat master and parish mission director. His response: “How about treating them as children of God?”

He remains bound by the charism of his religious community “to work for the poor and the most abandoned souls.” In today’s United States, he says, it is clear that migrants are the best fit for the category of poor and abandoned.

That Redemptorist charism follows closely the line articulated by Pope Francis. It is a religious community dedicated to reaching the marginalized and the poor. As the pope has pointed out frequently, few on the periphery are in greater need of the Church’s care and concern than undocumented immigrants, both in Europe and in the United States.

Tireless Crusader

“Immigrants are the ones. That’s why we are in this work,” Father Piedra says during a break from the unceasing cascade of immigrant appointments.

He works from 9 a.m. to 3 p.m. on immigration, with Friday his day off. The modest office includes Father Piedra and three coworkers. At night, he joins with his fellow Redemptorist priests in ministering to the parish. Those are long days and nights for a man more than a decade beyond the normal priest retirement age.

“I am not a person who wants to sit here and twiddle his thumbs,” he says about his hectic schedule and his reluctance to retire. There is little time for thumb twiddling.

Some of his time is spent in community meetings, offering immigrants an opportunity to learn their legal options. A few days a week he takes the subway to Lower Manhattan to advocate in court as well as in meetings with immigration workers. To cover all these services, he raises funds via the Redemptorist network.

Much of his time is spent amid the grind of government forms, evidence, and proof—a daunting obstacle of red tape and regulations even for those familiar with American culture and the English language. At the side of his desk are old-fashioned paper files with volumes of documentation on pending cases: stories wrapped in notes about rent receipts, birth certificates, and utility bills—all intended to prove an immigrant’s whereabouts through the years. For his clients, his services are absolutely essential. Almost everyone lives at poverty levels, so his services are free. When a case is won, sometimes a grateful immigrant will provide a donation of gratitude.

Frequently, nothing can be done. The parish regularly offers funeral services for immigrant family members who died in Latin America. They are unable to travel to their home countries, permanently separated from loved ones.

Most of his clients are Latinos. But one of the first cases in the Neumann office involved an Irishman seeking a work permit. There is the occasional Chinese immigrant seeking assistance, as well as Gypsies from Romania, perhaps the most persecuted group in Europe through the centuries, seeking political asylum. They were persecuted by the Nazis and other regimes. A judge in the system was inclined to support Gypsy claims.

“She retired, much to my chagrin,” says Father Piedra, lamenting how slight shifts in the system can have such an impact on people’s lives.

There are success stories too. Father Piedra is proud that he was able to assist a woman from Ecuador. She was married to a police officer who beat her up and chained her to a bedpost, forcing her to serve the prostitutes he would bring home. After one failed escape attempt, her husband’s beating resulted in the death of her unborn child. Being married to an abusive police officer, she had no legal recourse in Ecuador and fled. She was able to win asylum. However, such cases, borne out of domestic violence situations, are now officially not considered in asylum requests.

All in all, the system is getting more callous, in the eyes of Father Piedra. There are more bureaucratic tangles. A woman who applied for citizenship, thinking it was going to happen, had her green card expire. Now she is in legal limbo. Food stamps for the families of immigrants used to be granted as a way to feed children, who are often American citizens. But that is now being routinely denied. A Brazilian woman applying for citizenship had her visa stamp scrutinized. It took months to authenticate it.

About 80 percent of asylum requests are now being denied. One client from El Salvador testified to the murder of his sister, the girlfriend of a gang member. When he was told he was next, he fled. His case for asylum is under consideration, but the odds are increasing that it will be denied.

Immigrants fear the 4 a.m. knock on the door from ICE officials more than ever, says Father Piedra, as the government increases its enforcement of immigration laws, even for those whose only legal offense is having come to the country in the first place. Sometimes a main suspect, who might be a prime subject for deportation because of previous convictions, is caught, along with others who were in the vicinity and would never have been a target otherwise.

‘Wisdom Figure’

Through these obstacles, Father Piedra’s fellow Redemptorist priests who work with him at Our Lady of Perpetual Help admire his steadfastness and determination. Father James Gilmour, the pastor, has known Father Piedra for the past two decades in Brooklyn. “He is very loved,” says Father Gilmour about his fellow priest. “He is very venerated in the community.”

At Our Lady of Perpetual Help, which looms over the neighborhood of apartments, storefronts, and subdivided homes, Father Piedra’s work flows seamlessly from the mission of the parish. There are about 1,500 registered families, but more than 3,000 attend weekend liturgies. As in many immigrant communities, there is a reluctance to register, for fear that proof of their presence can be held against them. Father Piedra offers a consoling figure in a frightened community.

Every morning, Father Piedra finds time for private prayer. Perhaps from that source, he has been able to replenish his work with immigrants, often a long slog, and sometimes comes up against insurmountable obstacles.

“He is a very calm, tranquil, compassionate, and understanding person. He advocates. But he won’t be shouting into a bullhorn,” says Father Francis Mulvaney, the rector of the Redemptorist community at Our Lady of Perpetual Help. Father Piedra “is a wisdom figure” in the Sunset Park immigrant community, adds Father Mulvaney.

Occasionally, Father Piedra will take to the streets in immigrant demonstrations. At one, quoted in the Brooklyn Tablet, the diocesan newspaper, Father Piedra made no apologies for helping the most peripheral people, those without documents. “I haven’t met one single criminal,” he told the Tablet about the thousands of immigrants who have come to his office seeking help. “I’m not saying they don’t exist, I’m not saying they don’t sneak in, I’m saying I’m not aware of them.”

The president of the United States might disagree, but Father Piedra, the man with experience in the field, argues that those who come to him in Brooklyn “are decent, honest, loving family people wanting a better life and fleeing persecution.” They are God’s children, he will argue, and deserve the love and consideration owed to any other person on the planet. It is a radical idea at the heart of Christian dogma—backed up by the Gospels and the pope—that Father Piedra, fighting this battle into his 80s, is not giving up on, even when it is not glamorous, popular, or even ultimately successful.

“That, to me, is Christianity,” he says, looking around his office. “The people here are children of God.”

1 thought on “‘I Was a Stranger and You Welcomed Me’: Father Ruskin Piedra”

Was sorry to hear of the passing of Father Piedra yesterday May 11 2025 , as I stopped to talk to a parishioner and X coworker from where we worked at LMC hospital now NYU Langone hospital. My parents also from Cuba and devoted Catholics from OLPH loved Father Piedra , in fact I the son have a picture of Father Piedra with my parents, who have.passed away a few years. I the son would at times run into Father Piedra and he would give me a blessing. I ran into him around 8 months ago or so, as he was returning a package at a UPS store near where I live and he was waiting for his pickup and we spoke for awhile. And gave me a blessing. He was very much loved . RIP Father Piedra and May his memories be a blessing.