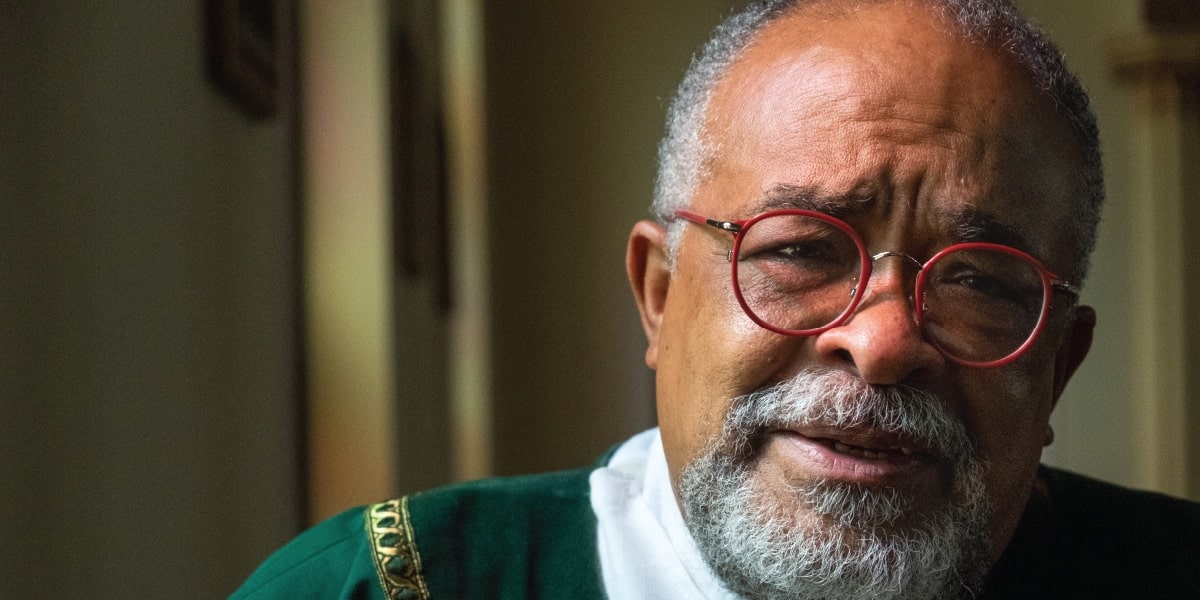

No more documents. No more commissions. Deacon Art Miller says what the Church needs to do to confront racism is to act.

Each of us has a narrative that has helped form who we are. Those stories are made up of pleasant experiences as well as tragic and harsh realities. For Deacon Art Miller, the latter have played a large part in shaping both his life and ministry.

Miller grew up on the South Side of Chicago, where he lived with his parents and three of his four siblings. For the most part, it was a typical life for a young kid—school, playing outside with friends, and spending time with family.

Typical, that is, until the summer of 1955 when one of Miller’s neighborhood friends grabbed the attention of the nation in a horrible way. That friend was Emmett Till, the 14-year-old young man who was brutally murdered for allegedly whistling at a white woman during a trip to Mississippi to visit relatives. It has been noted that, due to a speech impediment, Till often whistled when he began speaking.

Three days later, Till’s bloated body was discovered in the Tallahatchie River. According to reports, Till had gunshot wounds in his head, his body bore the marks of a severe beating, and his fingers were crushed. Barbed wire had been tied around his neck and weighed down with a 70-pound cotton gin. At his funeral his mother, Mamie Till, insisted on his casket being open so people could see what had happened to her son.

Emmett Till’s death served as a catalyst for the burgeoning civil rights movement. It also served as a catalyst for Miller’s lifelong advocacy for civil rights and justice. He recalls his personal connection with Till in his book, The Journey to Chatham: Why Emmett Till’s Murder Changed America (AuthorHouse).

His life shaped by that experience, Miller set his sights on making a change. He became active in the civil rights movement and, in 1963, he was arrested during a street demonstration of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. His arrest, he says, was “for not being obedient to what was wrong.” He was 17 years old at the time.

It was not, however, the last time Miller would get himself into what he calls “Gospel trouble,” playing off the phrase of the late congressman and civil rights leader John Lewis.

Ghosts of Hate

But there is a lifetime between those incidents. And it is a lifetime during which Miller says that, wherever he goes, he is “always consciously aware that I am Black and the impact of that.” He calls it the ghost of hate and says “it is the reality that follows me wherever I go. And no one sees it but me.”

He recalls a story from 1957 when he and his mother were walking home after the pastor said he did not want Black people in his congregation. Miller’s family had recently moved into the parish.

On the way home, Miller says his mother was gripping his hand tightly and saying that no one was going to push her out of her Church. She began attending daily Mass and sitting in the front pew.

“I began to understand we had to fight to be Catholic. . . and no one was going to prevent me from being Catholic,” he said in an interview with the Catholic Transcript, magazine of the Archdiocese of Hartford.

After college, Miller went into the Army where he constantly experienced incidents of racism. The only time it wasn’t evident, he says, was out in the field in Vietnam. But when he came home after the war, the reality of racism returned. Miller says he couldn’t get a cab to stop for him, despite the fact that he was in uniform. Eventually, a white police officer stopped one for him.

Miller says that ghost—based on experiences such as those—creeps up in situations such as when he goes to the store or his grandchildren’s school. It’s there when he first encounters someone. And it is the reason that he and his wife don’t go to unfamiliar restaurants in certain neighborhoods.

And while that ghost never leaves him, he says, “My ability to love gives me control over my spirit. I can’t allow profound disappointment to hinder what God has put within me.”

Answering the Call

When he was 12, Miller thought that he was called to be a priest. Unfortunately, the priest at his parish was racist and wanted nothing to do with him.

Then, Miller says, he discovered girls and the rest is history. Miller and his wife, Sandy, have been married for 49 years, and they have four children and eight grandchildren. He worked for years in the insurance industry before retiring and starting on a new path.

Miller recalls his travels through various parishes over the years as his family moved. At those different parishes, he had experiences that he now sees as God nudging him along. Miller and his family eventually landed at an Afrocentric church in Connecticut, where he says he met a wonderful priest.

“After about three months, he came up to me with some papers and said, ‘Fill this out; you’re supposed to be a deacon,'” recalls Miller. Despite initial hesitation, a few months later he found himself in the program for the diaconate.

“The reason I’m a deacon, honestly, is because God kept asking,” he says.

After his ordination, Miller was assigned to St. Michael Church in Hartford’s North End, which has been a center of ministry to African American Catholics since the mid-20th century. He then moved to St. Mary’s in Simsbury, which is located in a predominantly white suburb. And he brought his particular version of preaching, complete with “a lot of movement and hallelujahs,” along with him. It was not always welcomed.

He says that even though the parishes are only seven miles apart, “they are seemingly polar opposites. Yet the craving for hope in the divine God is still the same. The fragility of the human spirit is still the same.”

In 2005, he was appointed director of the Archdiocese of Hartford’s Office for Black Catholic Ministries, which has since closed. Its work has been taken up by the archdiocese’s Office for Catholic Social Justice Ministry. In June 2020, that office hosted a yearlong virtual conference in response to the US bishops’ 2018 pastoral letter on racism, “Rooted in Faith, Open Wide Our Hearts.”

These days, though, it may be easier to ask Miller what he’s not doing as opposed to asking what he is involved with. He serves as a certified spiritual director and works with various organizations, such as COMPASS Peacebuilders, a youth violence mitigation and reengagement program in Hartford. He also mentors former gang members regarding things such as education. He and his wife run Deacon Art Miller Ministries, where they work with women who are homeless or are about to be homeless to help them financially or emotionally. And, if that’s not enough, he also serves as the chaplain at Hartford’s Capital Community College.

Talk Less/Do More

At their meeting this past November, the US bishops voted 194-3 to renew its Ad Hoc Committee against Racism for a second three-year term. The committee, which was put in place in 2017, focuses on addressing the sin of racism. When asked about the committee only being ad hoc, Miller says, “Maybe it would make a significant statement that they have this regular committee on racism. The fact that it’s ad hoc means it will end. Racism hasn’t ended for 400 years.”

Miller says he is tired of committees and statements. What he wants to see, he says, is action. “They need to do something. And I don’t mean issuing another paper. We need to form a community of action.”

There has been progress in the Catholic Church when it comes to dealing with systemic racial issues, Miller says, but he feels we’re going backward.

“The Church is a direct reflection of our society, and our society is institutionally racist. The problem is our Church is supposed to redirect and heal our society and our society is supposed to be a reflection of the Church, but it isn’t.”

The Church, Miller says, is like a locker room. “The locker room is where you go to listen to the coach to figure out the game plan, to read the playbook, to figure out who your teammates are, and what your position is. After the locker room you have to go out and get in the game. Then we have to come back the next week to gain our strength to go out into the world where the game is played. We rely on what we’ve learned, what we’ve been taught.”

The Smell of the Sheep

Miller takes his personal experiences and perspective to public forums, houses of worship, schools, and universities across the country. He also attends marches and rallies, offering his perspective as a Black man. Far too often, though, he says, “I’m the only Catholic clergy at any of them. Period. The Church does not get involved in the street.”

The young people, he says, just as during the civil rights era, are a driving force for change. He tells the story of a particular Black Lives Matter rally he attended in Simsbury, Connecticut, about a month after the death of George Floyd. At some point during the rally, about 100 young people gathered in the middle of a busy street and were blocking traffic.

The police chief asked Miller for his assistance, so the deacon walked into the street and told the group, “I have been doing this for decades, and you don’t know what you are doing. You need to get out of the street and follow me so I can teach you.” The group followed him and listened to him tell them about how to protest in peace and how to make change. “If I had not been there, if the Catholic Church had not been there, I don’t know what would have happened,” says Miller.

He says that, too often, people use their dislike for the Black Lives Matter movement as a reason to not get involved. Miller says: “Then tell them what you do care about. Say, ‘I’m here because Black lives matter. I don’t agree with the organization, but I agree with the statement.’ Or go and do something else. There are all kind of organizations.”

In October 2015, Miller was arrested for the second time in his life when he and about a dozen other protesters knelt and blocked traffic as part of a “Moral Monday” demonstration in an effort to raise awareness that Black lives matter.

In an interview with the Hartford Courant days after his arrest, Miller said, “I’ve never wanted to look back on my life and see that I was on the wrong side of justice.”

He is not afraid to speak his mind when he sees the Church failing, either. He has even challenged his own archbishop, Leonard P. Blair of Hartford. After the killing of George Floyd, Miller says he heard from the heads of many of the different faith traditions in the area but not his own archbishop. Miller wrote to Blair expressing his disappointment, especially since Miller is the only African American deacon in the archdiocese. The two eventually met and the archbishop sent a letter to the priests of the archdiocese recommending that they read a piece Miller had written.

But beyond that, Miller told the archbishop: “I want you to come out with me into the streets. And I don’t want you to wear your collar, because your collar is power.” The archbishop agreed but has not been able to do so because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Miller says he will hold the archbishop to his promise, though.

That is because he believes, “If God were to give us an 11th commandment, I believe it would read: Thou shall not be a bystander.”

Resources

The National Black Catholic Congress

NBCCongress.org

National Black Catholic Apostolate for Life

BlackCatholicsForLife.org

US Bishops’ Ad Hoc Committee against Racism

usccb.org/committees/ad-hoc-committee-against-racism

6 thoughts on “A Catholic Response to Racism”

Hi,

My wife and I would like to say thank you for your daily reflections. We really enjoy listening to them.

God bless you for all your generosity, in serving the Lord.

We are parishioners of Our Lady of Fatima in Phoenix, AZ. We are blessed to have Mother Teresa’s Sister’s of Charity, right next door.

Do you sell T-shirts with Lord what are we going to do today?

God bless you,

Jerry & Janie Perdue

Good Morning Deacon Art,

It’s Easter Tuesday and I listened to your commentary on Mary Magdalene and thought it was so poignant and spot on. I do like it when you’re commentary shows up on my morning offering site. I am from Bristol Connecticut and now live in the Richmond Virginia area. So I feel connected to you in some way. I think I know the Bob and Karen you speak of! So, I googled you of course. You are quite a man and true servant of our Lord Jesus. Thank you for who you are and what you bring to our Catholics everywhere.

HI Art

Just want to say a few words of Thanks. I first see you on tube, and could feel your struggle and your passion, and you diven insperation . I live in Ireland and have a strong sense of Christian spirituality. Every Tuesday l listen to your short talk so powerful at times you make me laught, the green glasses your grandchildren gave you your are some grandad to have, and mug saying Lord what are we going today. I am a Grandad myself. I send you a blessing form Ireland,may God who blessed my country with St Patrick, bless you and your family on your ministry Journey. Thanks again for your powerful words, just before I finish, at this time I am John Michael Talbot he is singing the song We Are On Holy Ground. Frank

What a man! What a smile! What a Christian! What a leader!

Thank you Deacon Art for your continued dedication to our Faith, even when she hurts you.

You are a true Catholic. I listen to you your commentary on the Gospel every Tuesday .

You inspire me, help me in my faith journey and make me smile.

What are you going to do Today❤️

Dear Deacon Art Miller,

It was our pleasure to meet you in person in Virginia Beach Virginia these last few days. Your presentation of our “playbook” was so inspiring as is your Tuesday Reflections on the USCCB website. You have many talents and God is using you to spread His Word. Please tell your wife and the rest of your family, “Thank You” for sharing their Patriarch. May God Bless you.

Respectfully,

Edward and Edith Compo