Father Richard Leonard, an Australian Jesuit and media expert, explains how film can be a gateway to God.

In the 1954 film On the Waterfront, Marlon Brando plays Terry Malloy, a longshoreman who struggles to take a stand against the Mob-controlled union that has made life for workers unbearable. One scene in particular rouses a Catholic spirit. Karl Malden’s Father Barry gathers some of the men at the dock and, standing a few feet from the corrupt bosses, speaks out against the injustices the workers face.

“Some people think the Crucifixion only took place on Calvary,” the priest says, his voice rising to a howl. “They better wise up! Taking Joey Doyle’s life to stop him from testifying is a crucifixion. And every time the Mob puts the pressure on a good man, tries to stop him from doing his duty as a citizen, it’s a crucifixion.”

On the Waterfront was a film ahead of its time because, unlike many of its contemporaries, it tackled a social-justice issue with a Christian awareness. It won eight Oscars and is considered one of the finest American films ever made. But would it find an audience today?

Richard Leonard, SJ, a media expert with a lifetime of studying film, believes so. In an interview with St. Anthony Messenger, he says, “I think moral stories can still find an audience. There are films where the values are better and the material they’re exploring is very strong. I think there’s an audience for a story beautifully realized and acted. So I think it could work again.”

If On the Waterfront were released this month in the heart of the summer blockbuster season it would compete with the Cameron Diaz comedy Sex Tape, Hercules with Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson, and Jupiter Ascending starring Channing Tatum. These films are sure to bring in numbers while doing virtually nothing to deepen the faith of filmgoers. Why are films that feed the spirit so hard to find?

Leonard has devoted his life to that question. A graduate of the London Film School, he is the author of Movies That Matter: Reading Film through the Lens of Faith (Loyola Press), and is the director of the Australian Office for Film and Broadcasting. Leonard also has a PhD in cinema and theology from Melbourne University.

His work with that office is multilayered. They look at film reviews for the Australian Catholic Press, as well as censorship issues. They offer media education and, finally, pastoral care for people in the entertainment industry. Leonard, to be certain, is a formidable voice in film study and media analysis.

Film As a Teacher

Though cinema took a hit with the arrival of television in the mid-1950s and again in the 1970s it has always remained a cultural force, and Leonard understands its influence. “Film forms values. That’s why it is a teacher. It reflects back to us what’s happening in society in a very stark way.”

According the Motion Picture Association of America, in 2013 the United States/Canada box office totaled $10.9 billion, proving that it is a powerful medium. Yet it’s also a deeply personal one. Consider the experience of sitting in a darkened theater, close to the big screen, with surround sound. It affects us on a sensory and emotional level.

“When we’re looking at that screen and we’re laughing or crying along with the story, and because we have some psychological identification going on, then we’re dealing with our own story too. That makes it a very powerful teaching tool,” says Leonard.

But it needn’t be cinema only. Think of Netflix as an education center. They have hundreds of stories that can teach us about faith and humanity. Leonard cites the following films as ones that can accomplish that:

The Diving Bell and the Butterfly. This is a true story of Jean-Dominique Bauby, a man who suffers from “locked-in syndrome” after a massive stroke. “He wants to find hope, but there is only depression, and then an angel of light assists him to find meaning in suffering.”

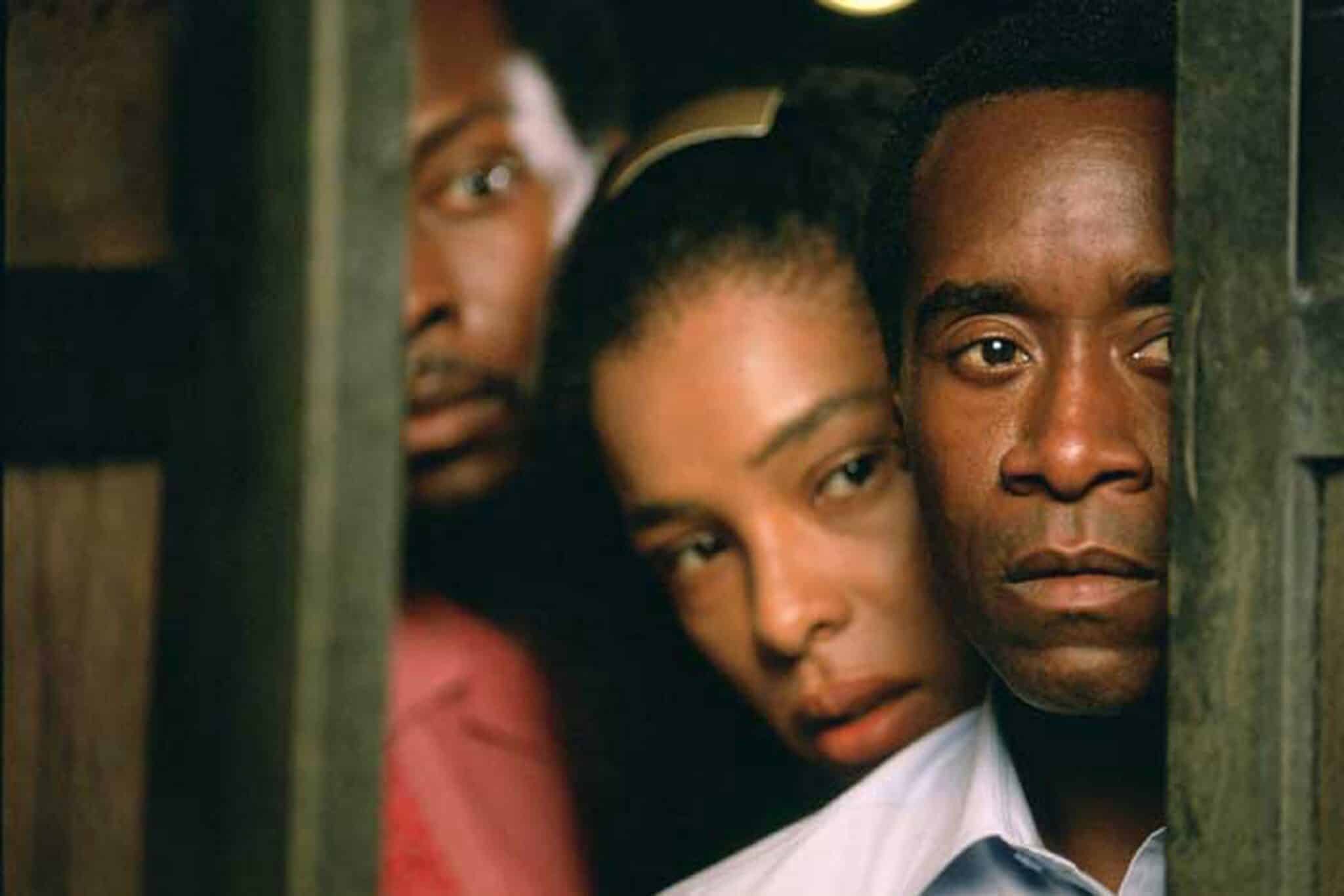

Hotel Rwanda. In an Oscar-nominated performance, Don Cheadle plays a hotel manager who rescues his fellow citizens during the 1994 Rwandan genocide. Of the relationship between Cheadle and Sophie Okonedo, who plays his wife, Tatiana: “It is one of the best portrayals of the fidelity and self-sacrifice in Christian marriage you are likely to see.”

Whale Rider. A young Maori girl in New Zealand, played by Keisha Castle- Hughes, must fight centuries of customs to lead her tribe. Leonard raves about this “simple and profound film about traditions, patriarchy, the power of women, and the pain of transition.” Leonard also finds parallels to our own Catholic tradition. “This story highlights that, while men may be the only ones allowed to be ordained, that does not stop Christ from raising up his sisters to be some of our greatest leaders.”

The Lord of the Rings trilogy. An examination of good versus evil, Leonard sees Peter Jackson’s interpretation of J.R.R. Tolkien’s work as fundamentally religious. “Keep a good eye on the most creative portrayal of the Trinity on the big screen, ” he says. “Gandalf is a Father who creates and calls. Frodo is a Son who takes on the form of the least, a hobbit, but whose destiny is to save. And the character Galadriel is a Spirit who inspires, enlightens, and comforts.”

Leonard believes that watching films such as these is a visceral experience because it taps into our own psychologies. “It’s a profound teacher and because cinema is a big screen, big sound, big experience, it has a big impact. Film also moves the emotions, and once you move people’s emotions to laugh or cry or be enraged, then film is plugging into emotions in your own life.”

A Mixed Blessing

Catholics must still wade through uneven waters to find films that touch on faith while films that degrade the human person are abundant. The two subjects that Leonard speaks of with the most zeal are sex and violence, particularly how they are represented. He establishes a good criterion for himself, as both a filmgoer and a media expert.

With cinematic sexuality, Leonard recalls how St. John Paul II put the term human dignity back into the international vocabulary. “That’s good criteria for me regarding sexuality and its portrayal in all media,” he says. “Is there a presentation of sexuality where the dignity of everybody is flourishing: the dignity of the people involved in the story or the dignity of the person who’s watching?”

Although Leonard admits that human sexuality is essential to certain films, how it’s delivered is critical.

“There can be betrayals of sexuality which are appropriate to the story and are dignified and very well done. There can sometimes be, necessary in the story, criminal sexuality. You can’t tell a sexual child-abuse story or a rape story without at least an implied presentation of horrific events. But filmmakers need to be very careful. They’ve got grave responsibilities in this regard. If it’s necessary to have criminal or abhorrent behavior presented, then I want it done in an implied way.”

Violence is tricky terrain as well. Boyz n the Hood, for example, vividly captured the life-and-death struggles of young African Americans in South Central Los Angeles. Violence, in that case, was an important component almost a supporting character. It’s when screen violence is made to look stylish or seductive that we’re encroaching dangerous territory.

“I want to know if it’s glamorizing or normalizing this behavior. Because it is neither glamorous, nor is it normal. It’s destructive. I want to make sure that it’s told with a terrific amount of attention to the impact of glamorizing or normalizing violence and, therefore, legitimating further violence.”

Violence is a close cousin with another trend that concerns Leonard, especially in American films: revenge. That theme can sometimes be handled in a comedic way, such as in The First Wives Club, about three 50-something friends who wreak havoc on their ex-husbands who abandon them for younger women. But retaliation is seldom handled with such a light touch. More often, revenge manifests through carnage. From Carrie to Kill Bill, Machete to Django Unchained filmmakers and audiences can be bloodthirsty, and that is a disconcerting trend.

“We don’t forgive. We don’t reconcile. We don’t deal with the issues,” he says. “We get our revenge. We have payback and retribution. And I don’t think it’s by accident. I don’t think film creates that phenomenon. I think it reflects back to us what’s happening in society.”

One film that still haunts Leonard as a mixed bag is 2004’s The Passion of the Christ. While he praises much of Mel Gibson’s depiction of the last 12 hours in the life of Jesus, he feels the film is unreasonably violent.

“Fourteen minutes of the scourging at the pillar blood and flesh and gore. I came out of the cinema wondering what was going on with Mel Gibson,” he says. “And yet there were Catholic bishops who wanted people in their dioceses to see it. I said to myself, ‘Hang on a minute! I’ve spent the last 15 years of my life saying implied violence is better than explicit violence. And here we have a film that’s explicitly violent.’ Now all of a sudden we’re saying, ‘Well, when it gets to the story of Jesus, all bets are off.'”

As a tool for evangelization, The Passion, to this expert, missed the mark.

“I don’t find shock ever to be the best way to evangelize,” he says. “I don’t find shock anywhere in the New Testament from the apostles, disciples, or Christ himself as a tool for reaching people. I want the evidence. Where’s the evidence that people came back to church or came to love Jesus more? If that’s true, then we should make The Passion of the Christ 2: Jesus Suffers Some More.”

Careful Consumers

Media, in all its forms, can be thorny. Therefore, Leonard says we must be critical of the media we consume. A dangerous game to play when considering film is to categorize certain ones as sinful without actually seeing them. Harry Potter is a prime example.

Though the franchise made a killing at the box office, it scared off many Christian filmgoers, who deemed it evil. Leonard asks that we dig deeper.

“The whole series is an incredible narrative about discernment, ” he says. “It’s all about making good and bad choices. Some people don’t like the films because it had witches and warlocks in it Satanism in sugar coating. Well, if that’s true, then we’re never going to read Macbeth again. Last I checked it had witches in it. So is any Catholic seriously going to say that because a witch or a warlock is presented, we can have nothing to do with it? I think that’s a serious poverty of imagination.”

Even the contentious Brokeback Mountain, about two Wyoming cowboys who share a secret, doomed relationship, in Leonard’s eyes was unfairly shunned out of fear and loathing. Many looked away when they should have looked closer. “Most condemned that film without even going to see it. That’s always a bad idea. It was much more complex than simply saying, ‘Oh, it’s a gay cowboy movie.’ It really wasn’t. One character’s dead and the other man is a shell of a human being. It’s incredibly sad. Their lies destroy them. It’s where sexuality can be so destructive.

“It worries me that we can be quick on the headline because we think a certain part of our community wants to hear that, when, in fact, if you watch the film all the way to the end, you can see there are other themes here. I don’t think you could’ve walked out of Brokeback Mountain and said that was a film promoting the gay lifestyle. I just don’t think it was.”

It doesn’t aid in our spiritual journeys to bury our heads in the sand, Leonard feels. “Catholics who say, ‘Film is evil an instrument of the devil,’ to them I would say, ‘You haven’t seen enough. You’re not as critical a consumer as you need to be.’ There are wonderful films that may not mention Jesus or the teachings of the Church or talk about the Gospels, but they’re singing our song.”

The Future of Film

When asked about the state of motion pictures, director Steven Spielberg once opined, “We have forgotten how to tell a story.” His own resume would suggest otherwise. He’s given us decades of movies that are both commercially successful and able to speak to something deeper, from The Color Purple to Schindler’s List to Lincoln. There are films out there like Spielberg’s that can tell a good story and feed the spirit. We just have to be open to them.

So what are Leonard’s hopes for the future of film?

“I wish the film community would be less interested in making money and more interested in the culture they form through the cinema they make, ” he says. “I’m not asking for only Bambi to be made. But I do think they’ve got to take much more seriously the destructive impact that some of these films have.”

Film not only takes a snapshot of where our society is, but it can also be prophetic. In 1998, Australian director Peter Weir gave us The Truman Show, about a man who begins to realize that his entire life is a reality show watched by the whole world. In its initial release, some critics, though in awe of Weir’s work, thought the film’s subject matter was a stretch even fantasy. But in our current culture of Housewives and Kardashians, it’s hard not to tip your hat to the film for its vision.

“Now all of these reality shows later,” Leonard says, “it’s not looking so stupid that, for the sheer sake of entertainment, we would con some poor person, because we do it in small measure for public entertainment all the time.”

Leonard seems cautiously hopeful that cinema can continue to offer audiences Catholic or otherwise stories that challenge and lift the human person. And, of course, he has his own preferences as well.

“I’d love them to tell more real-life stories, heroic stories. I like any film that tells a moral story well: films that get me to think about the implications of where we’re going. I wish we’d make more of those.”

Seven Films to See

Here are seven films that Father Richard Leonard, SJ, thinks every Catholic must see.

Of Gods and Men. “This is one of the finest religious and best Catholic films of all time. As their area is invaded by Islamic extremists, the monks have to discern whether they stay with their people or return to their native France.”

Babette’s Feast. “Pope Francis’ favorite, this film can be read as a parable of eucharistic hospitality and as an homage to an artist, in this case a culinary artist.”

Dead Man Walking. “Forgiveness does not deny things were done, but rises to say that despite what was done, I still forgive you. Sometimes we ask the question, “What would Jesus do?’ This film gives us the answer.”

The Last Days. “One of the most moving documentaries I have ever seen. It is like a biblical narrative: the story of scapegoat theology and the purification of memory.”

The Mission. “Great themes here of the wages of sin and death, repentance, conversion, penance, and forgiveness. Are pride, riches, and greed the motivation for our most destructive behavior? When is it justified to take up arms?”

Romero. “Oscar Romero was the most unlikely of social prophets, but became the voice of the poor against El Salvador’s military junta. This is a moving film about the martyrs and the cost of following Jesus.”

The Shawshank Redemption. “Andy is a Christ figure, an innocent man who is wrongly convicted and persecuted, but who nonetheless sets others free by how he lives his life. Against the odds, and even when the truth lets him down, Andy believes in hope and beauty.”