During the 50th anniversary of a key year in the civil rights movement, St. Francis School looks to the future in Mississippi.

It’s not as if St. Francis of Assisi School hasn’t struggled before. Back in 1951, in rural, segregated Greenwood, Mississippi, the very idea of a school for black children run by northerners (Catholic priests and nuns) was an affront. Yet the Franciscans stood by their witness at St. Francis of Assisi Mission, supported the civil rights movement—in which Greenwood played an important role—and participated in the change and growth of their community.

Sixty-seven years later, though, Greenwood’s Leflore County has the lowest-ranked public school system in Mississippi, which means it’s one of the least effective in the United States. Even so, St. Francis School, an alternative for the local black community, and increasingly for Hispanic immigrants, struggles to stay alive. “It’s been precarious from the get-go,” observes Brother Craig Wilking, OFM, a parish staff member. “Now we’re at a stage of listening to the community again and helping them to craft a solution.”

Place in History

St. Anthony Messenger took a trip to Greenwood to see for ourselves this ministry of Franciscans and their partners, the Franciscan Sisters of Charity and the lay staff of St. Francis School. It is a dark, evening drive from the interstate for over 100 miles across the countryside into the edge of the Mississippi Delta, along the Yalobusha River. Greenwood is 130 miles from Memphis and 90 miles north of Jackson, the state capital. A welcome sign, through a rainy windshield, declares Greenwood to be the “Cotton Capital of the World.”

Greenwood, population 16,000, was the cotton capital of the world in the 19th century, which made it a center of slavery. Dramatic change has come over the decades since the civil rights movement, but still, says Father Joachim (Kim) Studwell, OFM, the church’s pastor, “Everything is seen through the lens of race.” For example, he says, there are still people in town who resent that, 50 years ago, then-pastor Nathaniel Machesky, OFM, took sides in favor of racial equality, helping to organize the 20-month-long Greenwood Movement boycott.

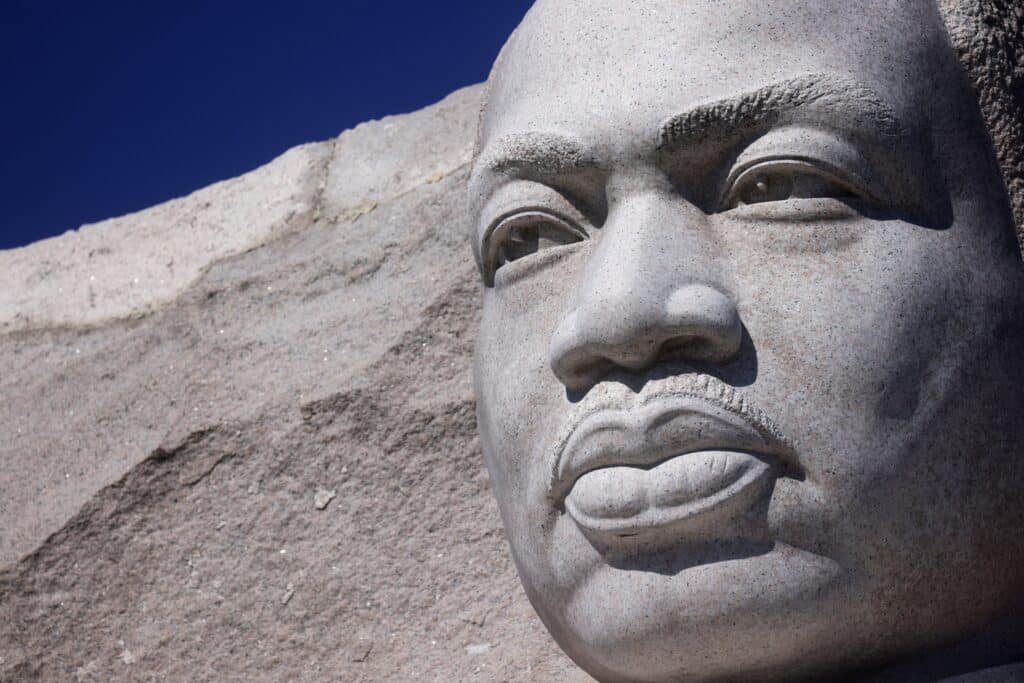

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. himself visited St. Francis of Assisi School in March 1968, only three weeks before his Memphis assassination. During the Greenwood boycott, which was reenergized by his death, shots were fired into the church, the Ku Klux Klan distributed anti-Catholic pamphlets, and even a firebomb was directed at St. Francis Center, a community outreach facility. Later that year, the Greenwood Movement resulted in changes in hiring practices and “the use of courtesy titles with black customers,” according to February’s anniversary story in Greenwood’s daily, The Commonwealth. That tiny step is a clue to the intransigence of racism here.

These days, according to art teacher Brother Patrick McCormack, OFM, most young people who have a chance move out of town as soon as they can. But not everyone. Tonight at St. Francis Mission, young ones in Greenwood are celebrating their history in a school performance to a packed church full of parents. We find a space near the edge of a brimming parking lot as the annual Black History celebration is finishing up.

There have been speeches (“I Have a Dream” and others), dances, and songs from the children, and the entire school has just sung the civil rights movement anthem, “We Shall Overcome,” joined by a glowing audience of family and friends. As parents and children mill about in the church-become-theater, Brother Mark Gehret, OFM, pushes a dust mop along the altar floor, cleaning up after the excitement (he keeps the facilities in good shape here). Tomorrow morning there will be Mass for the children.

Faith-Based Education

Among those who grew up and stayed in Greenwood is the principal of St. Francis School, Mrs. Jackie Lewis. She, her mother, and her daughters are all graduates of the school. Lewis returned two years ago because the school needed her help as resources became fewer and fewer, she says. “My two oldest ones attended up until eighth grade. We still had eighth grade then, but for the two youngest ones, it was sixth grade.”

It was a different school for her. “We had basketball, we had a band, but we were fortunate enough to have more Franciscans,” she says.

Jackie had retired as a public school administrator, returning to St. Francis first as a fifth-grade teacher, then as principal of the 89 students. “It’s a challenge,” she says. “It’s very different from public school, where you have various people on the top levels who assist with different things” such as financial planning and curriculum. “Here you are everything, from the janitor, the cook, all the way up to the principal—and everything in between!” she says with a laugh. She calls the school a “real gem” in the community. “I’m so invested in the school, in the parish, that I don’t want to see it just dwindle away.”

St. Francis School ends after sixth grade, and most students can’t afford the local charter (private) school. But for the children attending seventh grade in substandard public schools, the efforts of St. Francis School have not been wasted. “You’re going to have some children who are going to perform regardless,” she observes. “They’re not going to be a discipline issue, and they have developed morals and standards at St. Francis. I think when you learn those things early on, they stick with you.” Many St. Francis students eventually make it to Mississippi Valley State University. Something has worked.

Yet hurdles remain. Persuading the parents toward faith-based education is harder these days than it was in the past, Lewis observes. Oh, and there’s money. “If we had more dollars available, we could probably serve those people who desire to bring their kids here but can’t,” she says. And she would have a stronger teacher-recruitment program. The traditional source of teachers, those retired from the public schools, has dried up. “Teachers are so burned out when they leave public schools, they’re not going anywhere but home.” Higher salaries might draw them out.

We got to see a bit more of the school’s can-do attitude about an hour later, when the children celebrated the 85th birthday of their retired pastor, a fixture around the school. Father Camillus Janas, OFM, had been honored at Mass earlier. Now, Principal Jackie, along with the Franciscan staff (including Father Camillus himself) serve ice cream as the children come through the cafeteria line, one class at a time. At Mass earlier, as a few of the young students had proudly come forward with grateful testimony, this stalwart friar actually choked up—the accolades were a surprise. But soon he was back to his homily and giving the students wise advice: Work hard, keep studying, be kind to one another. The ice cream seems a reward for that.

‘Children of God’

St. Francis School hangs on a thread these days, but that doesn’t deter Franciscan Sister of Christian Charity Kathleen Murphy. Her Wisconsin-based congregation serves communities in need in various parts of the United States. She and her sisters are part of the fabric that has held things together here. They’ve been at St. Francis Mission for 35 years, teaching in the school, serving the parish, doing community outreach, and nurturing a group of Secular Franciscans, which has grown since the parish’s earliest days. In addition to working as religious-education director, she teaches kindergarten. “These are amazing children of God. There’s a lot of hunger—and I don’t mean for food. In so many cases, there’s a lack of supporting families.”

There’s a lot of “social suffering,” she says, “a lack of understanding of black and Hispanic culture. . . . I think that is something that education can address.” To her, it’s all within a greater context of evangelization, “such a fertile field here,” she says.

Educational segregation is still the norm in Leflore County, she observes, with black and Latino students in the public schools and white students in private ones—a long-standing arrangement for decades in much of the South, including the Mississippi Delta. Before the civil rights era, black children were in segregated schools with leftover resources from the white public schools. After federally mandated public school integration, most white families headed to private schools. Funding for public schools then declined. “I don’t think they [white community leaders] really care about it,” Sister Kathleen says.

“For many of our kids,” she says, “this is their faith experience, ” a key component of St. Francis School. The number of unchurched families has grown in recent years, she notes. “We teach the Catholic faith, whether the students are Catholic or not. Most of ours are not, but nonetheless they receive daily religion class,” she adds. “They go to weekly Mass, have reconciliation prayer services, have their throats blessed, receive ashes on Ash Wednesday, and so on.”

At St. Francis School, there’s also a “sense of safety” and “a sense of community,” she says, that you won’t find in the local public schools. “They’re well educated here. That’s something the parents know.” It’s all about the test in the public schools, she notes, referring to competency tests associated with public school performance. At St. Francis, there are strong academics, “but they need to love learning first.” That’s what she tries to achieve in her kindergarten classes.

“We feel as Franciscans that this is a home for us. You know it, it’s a perfect fit, and our sisters, no matter who have come, end up being in love with the people.” Her sisters, she says, journey with them. “Francis didn’t try to fix the world,” she explains, but rather, “he would walk with people; he would change their bandages.” That attitude drives her work.

Uncertain Future

The Franciscan Friars of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary Province (OFM), based in Franklin, Wisconsin, have operated this mission since its 1951 beginning. But ministries such as this school compete both for friars and for funding as resources diminish.

In fact, the school, funded these days in part by several Franciscan provinces as well as by outside donations, is now living on a year-to-year basis, its future in question. The friars, sisters, tuition-paying parents (as well as those paying partial tuition), and the Diocese of Jackson are all considering whether the school will continue.

But the need is still there. “Racism is more covert today,” says Father Kim, pastor. Institutions, such as a local hospital, needed to integrate to maintain federal funding. “But every hospital room is a private unit,” keeping races apart. There’s an academy for white students of means.

“This is the reality we live in, and we’re trying to provide an alternative,” says Father Kim. One of his challenges is to engage the families more fully financially, which was not as strong an emphasis in the past.

“We basically are trying to move from a paternalism model to co-responsibility,” he says, an initiative started through efforts of the school principal. She launched a school advisory council—a new idea here. Father Kim observes that some of the families find resources to send their children to the private charter academy after sixth grade; he’s leaning on these families to pay more while they’re still at St. Francis School.

“We want to get away from the mission mentality,” says Brother Craig, who oversees fund-raising for the school, “but you also have to see that we’re in one of the poorest places in the country.” There will be no quick fixes. Brother Craig, a nurse by training who came to St. Francis from a rural health clinic in nearby Tutwiler, Mississippi, agreed to move here because the school needs him. His cool reasoning and fact-dependent approach from nursing may well be the medicine St. Francis School needs at this precarious time.

“Our hope is to discern what God wants to do with what we have here,” says Father Kim. Then this joyous man quips, “I have no idea!” He’s only partially kidding. Once again serious, he offers, “As St. Paul says, ‘We walk by faith, and not by sight.'” Then Father Kim adds, once again laughing, “I identify with that!” These are days of uncertainty at St. Francis Mission.

A few weeks after our visit to Greenwood, Brother Craig sent an e-mail after Principal Lewis had talked with parents, one family at a time: “We will be open again in the fall.” The staff at St. Francis of Assisi school will continue to teach, Father Kim and Brother Craig will continue to develop a sense of co-responsibility among the families and in the parish, and they all will continue to discern the next steps for St. Francis of Assisi School. As Sister Kathleen would say, “That’s the spirit of what we do.”