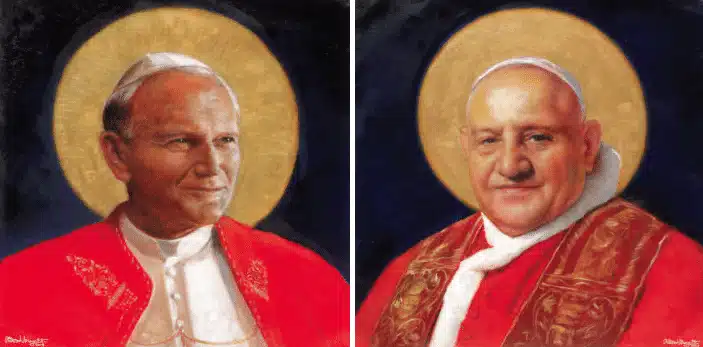

It was certainly no surprise when Pope Francis declared that John Paul II (1978-2005) would be the next papal saint. The Polish pope’s canonization seemed only a matter of time, just like that of Mother Teresa.

However, in what is becoming his characteristic way of catching everyone unaware, Pope Francis declared not only that he was naming Pope John XXIII (1958-1963) a saint—and at the same time waiving the customary requirement of a second miracle—but also that he would canonize John XXIII and John Paul II together in the same ceremony on April 27.

Previous Papal Saints

Popes John XXIII and John Paul II will join 81 prior popes who have been canonized over the centuries. This comes out to about a third of the more than 260 successors to St. Peter. Most date to the Church’s first few centuries when many bishops of Rome were martyred during the episodic persecutions of polytheistic Roman emperors, often looking for scapegoats for their own failures in moral, economic, and political leadership.

Following St. Peter, who is clearly his own category, every one of the next 48 bishops of Rome, except one, was canonized by local acclamation. The standout is Liberius, who was bishop of Rome 352-366. A weak man, he bent to political pressure and appeared to undermine the Nicene Creed by condemning its architect, the theologian Athanasius. That Nicene Creed is the same one we pray at Sunday Mass today.

The next 500 years of Christianity saw another 30 papal saints, culminating in Pope Gregory VII, who died in 1085 and revolutionized the papacy. Remarkably, before the upcoming canonization of John XXIII and John Paul II, only three popes have been declared saints since then: Celestine V (the pope who resigned in 1294), Pius V (1566-1572), and Pius X (1903-1914). Not counting the two new upcoming papal saints, there are nine other popes who have been beatified but not yet canonized.

Canonizing Vatican II

Why is Pope Francis canonizing both men—and doing so at the same time? On the one hand, and at a certain surface level, if we buy into caricatures of John XXIII as a progressive pope and John Paul II as a conservative pope, the dual canonization can be seen as an attempt to satisfy two wings of the Church and unite them in a big tent. This was the conventional interpretation given when Pope John Paul II beatified Pope Pius IX (1846-1878), a staunch papal monarch and no friend of modernity, along with John XXIII, a pope with a far softer and more collegial touch, who opened the Church to the world (and the world to the Church) in the 1960s.

Pope Francis certainly envisions the Catholic Church as something like Noah’s ark, with all sorts of animals packed together: we may not like each other, but we are in the same situation and might as well get along for the common good in Christian charity. It could well be that Pope Francis feels the need for the support of all voices inside the Church as they are represented, if only superficially, by these popes.

Just a few weeks after his own election, Pope Francis prayed at the tomb of Blessed John Paul II on April 2, 2013, the eighth anniversary of his death. That is not unexpected, but in a signal that we all missed, that day he also stopped at the tombs of Blessed John XXIII and St. Pius X.

But we must remember that the Catholic Church is far more complex than caricatures and factions. It defies standard labels. It cannot be forced into common definitions of right and left, conservative and progressive.

Take the three popes now forever linked together, for example. Certainly John XXIII, John Paul II, and Francis are all doing their duty as bishops, let alone as popes, of conserving the faith. But all three are at the same time leading voices in protecting the poor and unborn, advocating for social welfare and human rights, and speaking for those who have been left behind in a world of materialism and wealth that is out of control. So are they right or are they left?

We sometimes forget that John Paul II was as much a critic of capitalism as he was of communism. Moreover, Benedict XVI was a complex voice on social issues, but call him a progressive or liberal, at least on those issues, and most would laugh at you. Those labels, and in particular American political labels, simply fail to describe and do justice to the complexity of Catholic teaching and values.

A Tale of Two Popes

John XXIII and John Paul II were very different men. John XXIII spent most of his career as a diplomat, not a diocesan bishop; elected at 77, he had a short papacy. He was older, quite obviously of wide girth, and fairly quiet. John Paul II was an extrovert, an athlete, and a relatively young pope at 58 who ended up with the second-longest papacy in history, behind that of Pius IX (and Peter’s traditional 35 years).

Despite his advanced age and somewhat old-world career, John XXIII conveyed a greater openness to new ideas and shared governance. And while an openness to the world’s diverse cultures characterized much of the first half of John Paul II’s papacy, that approach took a backseat to the firmer, more centralized hand he played in internal Church affairs in the second half.

For all their apparent differences, however, both men shared a love of life and a sense that the Church needed to reach far and wide to spread the Gospel in a changing world. Taking up this challenge of balancing Church tradition and renewal while the world was often at war also linked them.

As a young priest, John XXIII had served as a military chaplain in World War I. During World War II he held complicated diplomatic posts in dangerous places, frequently doing what he could to aid Jews in escaping totalitarian regimes. John Paul II’s formative years and career were spent fighting Nazism and Communism. Like John XXIII, he had positive personal experiences with Jews that significantly impacted his papacy and changed the Church.

Most important, both popes were men of Vatican II (1962-1965). As Pope Francis said of John XXIII, “He was also a man of the council: he was a man docile to the voice of God, which came to him through the Holy Spirit, and he was docile to the Spirit. Pius XII was thinking of calling the council, but the circumstances weren’t right. I believe that John XXIII didn’t think about the circumstances: he felt and acted. He was a man who let the Lord guide him.” Vatican II was specifically mentioned when John XXIII’s canonization was announced and the lack of a second miracle had to be explained. As Vatican spokesman Federico Lombardi, SJ, said, “He is loved by Catholics, we are in the 50th anniversary of the council, and, moreover, no one doubts his virtues.”

Karol Wojtyla attended Vatican II as a young bishop and archbishop. With Paul VI and Benedict XVI, John Paul II played a critical—and not uncriticized— role in interpreting and implementing the council. By canonizing John XXIII and John Paul II together, it appears that Pope Francis is, in a sense, canonizing the council. Perhaps he is affirming, too, the multiple ways of understanding Vatican II’s meaning as a blueprint for the future that grows vibrantly from a centuries-old tradition that firmly grounds the Church.

It may be, too, that Pope Francis will seek to draw on the papacies and followings of both men to shape and steer his own papacy. After all, in some senses John XXIII had the easy job: he called the council but passed away before the enthusiasm waned and the hard work of reconciling competing ideas of making Vatican II began. That fell to Paul VI, whose own papacy was marked by the turbulent 1960s and 1970s, and especially to John Paul II, the last of these four who was at Vatican II.

Church history shows that all councils and indeed every revolution tend to swing in what the German philosopher Hegel called a dialectic: one interpretation (thesis) at first carries the day but then it is challenged by its opposite interpretation (antithesis). In a best-case scenario, a synthesis then takes place that draws from the constructive ideas of both sides.

As we celebrate the 50th anniversary of Vatican II’s sessions and documents, it may well turn out that Pope Francis will be the great synthesizer of Vatican II—and we might suppose that he will be praying for the guidance, wisdom, and intercession of both St. John XXIII and St. John Paul II.

How Is a Saint Made?

Blessed John Paul II revised the saint-making process in 1983 with some significant changes, in response especially to modern science and more sophisticated historical research methods. He reduced the number of miracles needed for beatification to one and for canonization to two.

At one time, as many as four miracles were needed; some say modern medicine might force removal of these altogether at some point. Also, John Paul II removed the adversarial aspect of what used to be essentially a trial of the candidate conducted by the person known commonly as the “devil’s advocate,” who challenged the candidate’s alleged sanctity. Now, the promoter for the faith, as the official is known, takes the position that the candidate is indeed saintly unless it can be proven otherwise.

While the process ends with the pope considering the recommendation of the team of investigators from the Vatican’s Congregation for the Causes of Saints, today it still begins locally as it did throughout Church history. People recognize their neighbor and ask the bishop to investigate this person designated as a servant of God.

There is a five-year waiting period in nearly every case, though recent memory has seen it waived twice: for Mother Teresa and John Paul II. A local postulator begins to gather evidence from eyewitnesses, if they are still alive, and to assemble a paper trail to examine what the candidate said and wrote. Once that portfolio is complete, it is sent to Rome and assigned to a relator, who reviews the material and sends it along for consideration.

Once the pope decides to name a candidate a saint, a date is set for the ceremony and the person is assigned a feast day, which is frequently the date of the new saint’s death.

Pope Francis on John XXIII and John Paul II

In his remarkably frank and informal press conference with journalists on the flight back from World Youth Day in Brazil in July 2013, Pope Francis spoke about his two soon-to-be-sainted papal predecessors. He was asked by the journalist Valentina Alazraki, “What is, according to you, the model of holiness that emerges from them both and what is the impact that these popes have had on the Church and you?” Here are excerpts from Pope Francis’ long response to that question:

“John XXIII is a bit like the figure of the country priest, the priest who loves all the faithful, who knows how to care for the faithful, and this he did as a bishop, and as a nuncio. How many baptismal certificates did he forge in Turkey to help the Jews [during the Holocaust]! He was courageous, a good country priest, with a great sense of humor and great holiness . . . . He was meek and humble, and he always concerned himself with the poor . . . .

“Regarding John Paul II, I would say he was the great missionary of the Church: he was a missionary, a man who carried the Gospel everywhere, as you know better than I. How many trips did he make? But he went! He felt this fire of carrying forth the word of the Lord. He was like Paul, like St. Paul, he was such a man; for me this is something great.”