Along treacherous stretches of borderland between the United States and Mexico, Franciscans are working to respond to the humanitarian crisis there with faith and compassion.

1,954 miles. It’s roughly the distance from Chicago to Los Angeles. It’s also the length of the US-Mexico border, from where the Rio Grande empties into the Gulf of Mexico in the east, to the Pacific coast in the west. Much of the terrain along the border is rugged, arid, and in many places inhospitable, despite its natural beauty.

When you hear the word desert, scorching temperatures often come to mind, and that part is certainly true. In the Sonoran Desert, for example, summer temperatures typically soar well above 100 degrees, nearing 120 some days. However, desert nights can be surprisingly cold, dipping into the 30s or even upper 20s. Death from exposure can easily happen at temperatures below 50 degrees. Add to this the lack of access to water, and traversing this region by foot becomes even more daunting. Yet every year, massive numbers of migrants attempt the passage. And every year, sadly, many don’t survive the perilous journey.

Whether those who attempt to cross make it here and find a way to stay, get caught and deported back across the border, or perish along the way, they are largely a shadowy, nameless, and faceless group in American society. They are nearly invisible, but when they are seen, they’re often viewed with distrust, misunderstanding, and hatred.

In St. Francis’ time, the lepers in the valley below Assisi were seen in much the same way. Today, migrants and other marginalized groups are the lepers in our society. And just as St. Francis realized in one of the most important moments in his life, we are called not only to see them, but also to embrace them, to love them as Christ does. Following in the footsteps of their founder, Franciscans and associates are reaching out with compassion in the borderlands. Far from turning away, they have chosen to go where the pain is with the aim of relieving suffering and promoting justice. They are living out what Pope Francis called for in his 2021 message on the World Day of Migrants and Refugees: that we “advance together toward an ever wider ‘we.'”

Perception vs. Reality

In the summer of 2018, Sister Maria Louise Edwards—who belongs to the Felician Sisters of North America—happened upon a photo essay in the New York Times titled “They Have a Mission in the Desert: Finding the Bodies of Border Crossers,” by Simon Romero, with photos by Victor J. Blue. The story stopped her in her tracks. It described the efforts of an organization called the Águilas del Desierto (“Eagles of the Desert”) to recover the remains of migrants who died during border crossings.

“I was really moved by what I read, but, at the same time, it was like this complete disconnect because I couldn’t understand how all of this was happening, and this was the first I had heard of it,” Sister Maria Louise says. The photo essay showed a group of volunteers braving the heat to help a man locate the remains of his brother. As Sister Maria Louise learned more about the Águilas, she saw that the organization was helping to bring closure to families and dignity to those who died in the desert.

Sister Maria Louise Edwards found out about the Eagles of the Desert in a New York Times photo essay. A discarded purse and a child’s shoes are physical reminders that migrant families are making the dangerous crossing to the United States. Left: Courtesy of Sister Maria Louise Edwards; Right: Henri Migala

At first, Sister Maria Louise offered to help the Águilas by crafting wooden crosses, which volunteers would place wherever human remains were discovered. Soon she felt the call to do more, but, by her own admission, she didn’t know much about the humanitarian crisis at the border.”I didn’t know what was the truth and what wasn’t,” she says. “You get all these stories about the people crossing: They’re criminals, drug dealers, people trying to do their worst in our country.” But that narrative didn’t gel with what she was finding out as her relationship with the Águilas developed.

With all the competing information and politics surrounding the issue of migrants crossing the US-Mexico border, Sister Maria Louise opted for firsthand experience to illuminate the truth. “I wanted to go and see for myself,” she says. So, two months after building her first crosses for the Águilas, she walked out into the desert with them on a search.

One Little Shoe

It’s not uncommon to find abandoned articles of clothing in daily life: a stray glove in a park during winter, a pair of forgotten sunglasses left poolside, or perhaps an oddly placed single sock on a sidewalk. And there’s usually nothing particularly impactful about these items, except maybe as indicators of absentmindedness or our throwaway culture. However, it was a little girl’s shoe that forever changed Sister Maria Louise one day in the arid borderland of southern California and Mexico.

In October 2018, Sister Maria Louise participated in her first search with the Águilas, which took place near the sparsely populated area of Ocotillo, California. “We started our search at the border with our backs to Mexico,” she recalls. “We were so close, we set off the underground sensors, and the Border Patrol called us to ask, ‘Are you guys really out there?'” And indeed they were. The group was looking for a 19-year-old man who had been missing for several weeks.

“Within two hours, we found a skull,” Sister Maria Louise says. “That was a very impactful moment for me because I had never seen a skull, let alone one just lying on the ground. I remember thinking, This is not our culture. This can’t be my country.”

The group went on to discover a rib cage and pelvis. It was determined that the remains belonged to a woman, not the 19-year-old man they were looking for, but it could mean closure for another family waiting in anguish for news about their lost loved one.

As the search continued, Sister Maria Louise found herself walking across a large boulder. “Right at the edge of the rock was a little girl’s shoe,” she says. “As I looked closer, there was still some of her foot in the shoe. I don’t think it was a coincidence that God brought me on my first search to find a woman and child. Not a gang member, not a criminal—a woman and a child.”

When faced with such a devastating discovery, the urge to recoil is powerful. “It’s a real battle within yourself,” Sister Maria Louise says. “You can shut down. You can push away the suffering. You can push away the unbelievable reality of what you’re standing there looking at: a body. That for me is the real challenge: to let it still impact me, to let it still hurt.” Ultimately, the Christian response kicked in for Sister Maria Louise. “You run toward the suffering; you don’t run away from it,” she says.

A Daughter’s Wish

In running toward the suffering happening at the US-Mexico border, Sister Maria Louise and others engaged in humanitarian efforts often come face-to-face with the sheer magnitude of attempted crossings, the result of powerful geopolitical and economic forces. According to US Customs and Border Protection, over 7,000 people have died trying to cross the border since 1998, though that number is likely higher, as an additional 3,000 people are listed as missing. It’s quite possible that recovery efforts will locate and identify the remains of some of these missing souls, but, sadly, many of those lost to the desert will never be found. However, the Águilas and organizations such as Border Angels and No More Deaths are working to change that.

The Águilas del Desierto were founded by a man named Ely Ortiz, whose brother and cousin had gone missing while attempting to cross into the United States in 2009. When no agency on either side of the border would help him in his search, Ortiz and one other human rights activist went walking into the desert to bring closure to his family and a dignified burial for his loved ones. After Ortiz found his family members’ remains, he realized that there must be many more people who have gone through the same ordeal.

“I know the agony of losing a loved one to the desert,” said Ortiz in the 2018 New York Times photo essay. “The desert is like a lion, stalking both the strong and the weak. The desert could devour any of us.”

A volunteer carries a cross with him while on a search. Whenever human remains are found, volunteers leave a cross at the site and say a prayer for the deceased person and his/her family. Authorities are then contacted and provided with the exact coordinates of the location. Photos: Henri Migala

What started as essentially a one-man army, the Águilas now have a dedicated core group of volunteers, including Henri Migala, who has spent decades working in the areas of humanitarian aid, public health, and disaster response. “I first heard of the Águilas when an ad for them popped up in my Facebook feed,” Migala recalls. “It was a short blurb about recovering the remains of migrants in the desert. I sent them a message asking if I could volunteer, and I received a very kind and welcoming response inviting me to the next search. I’ve been going ever since.”

Now having spent four years with the Águilas, Migala’s experiences on searches continue to resonate with—and haunt—him. “I’ve been on three searches where adult children were looking for their fathers,” he says. One of those searches involved a young pregnant woman who was looking for her father. The woman, who lived on the US side of the border, was getting close to her due date and hoped her father could come to be present for the birth of her child. The father, realizing that the visa process would take at least five years, decided to try to cross but went missing near some irrigation canals.

“We were looking for his body with his daughter, who was eight months pregnant, and her anguish was just palpable,” Migala says. “It was so surreal and bizarre to share space with this young woman, who knew that her dad was missing because she asked him to be with her.” Although the group didn’t find him that day, Border Patrol scuba divers located his body not long after. The young woman was so traumatized and distressed that she went into premature labor.

Strength in Numbers

Fortunately, the Águilas have grown in visibility, with their mission shared in the New York Times, on CNN and PBS, and on their own website (AguilasdelDesierto.org) and social media presence on Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube. Their YouTube channel is particularly impactful, as footage of searches reveals the unforgiving landscape border crossers face. With increased awareness, more people from across the United States are volunteering with the Águilas.

Their work now includes rescue as well as recovery efforts. In the past year, the Águilas have rescued over 180 people from almost certain death. As Sister Maria Louise puts it, many of those rescued “are actively dying” when the Águilas find them. Typically, there are 20 to 25 volunteers on a search, though some searches have had 50 volunteers. The scope of their searches has also expanded to New Mexico and Texas.

Both Migala and Sister Maria Louise are quick to point out the delicacy of working along the border, where there is a network of complicated relationships to maintain, including communicating with distraught families, working with Border Patrol, and even getting information from various sources on the last whereabouts of a missing person.

In particular, a stable relationship with Border Patrol has proven invaluable. “If we did somehow damage our relationship with Border Patrol, then definitely fewer lives would be saved,” says Sister Maria Louise. “Our relationship with Border Patrol is very important. We’re very careful to keep that relationship positive.”

Moreover, the Águilas must remain explicit in their mission to avoid misunderstandings and any potential legal threat to their activities. “Of course, we are not involved in any way in helping people cross the border,” Migala says. “Our only mission is to help reduce death and suffering along the border—and we do that by trying to get people not to cross the border illegally, rescuing those who need rescuing, and recovering and repatriating the remains of those found in the desert.”

After receiving medical care, many of the migrants who are rescued by the Águilas are deported back across the border, only to attempt another crossing later. As Migala mentioned, the Águilas have made efforts to prevent illegal crossings. Members of the Águilas have visited numerous migrant centers in Mexico, giving presentations and distributing brochures and flyers detailing the dangers of attempting border crossings. They plan to expand these educational campaigns to a number of countries in Central America to raise even more awareness.

Despite all the darkness and desperation she has witnessed out in the desert, Sister Maria Louise takes heart and finds strength in her core spirituality. “I’m so grateful that I’m a Franciscan,” she says. “It’s just so much a part of who I am and how I want to see the world. Everything is relationship.”

This fundamental understanding of our interconnectedness, all parts of the body of Christ, helps Sister Maria Louise face each person she encounters in her work with the Águilas with care and compassion.

She also realizes that her work with the Águilas is grounded in the Gospel. “We’re all supposed to be ushering in the kingdom of God, but what is the ‘ushering in’ that I’m doing?” asks Sister Maria Louise. “I don’t want to usher in a kingdom where it’s OK that people are dying in the desert. That’s not the kingdom of God that I want to see come into this world. I want to say this is wrong. I want to say this life mattered. This little girl mattered.”

Ministering to Migrants Facing Deportation

When migrants get deported to Mexico at the Raul H. Castro Port of Entry in Douglas, Arizona, Brother David Buer, OFM, is often on the other side, waiting to receive them. “It’s not unusual for over 150 migrants to come through in one day,” says Brother David, a Franciscan friar who has worked at the US-Mexico border in Arizona for over 15 years.

Across from Douglas is the Mexican town of Agua Prieta, in the Mexican state of Sonora. Many of the migrants who are deported there are hungry, tired, and even unsure of where they are. “The US side has a policy called lateral deportation,” says Brother David.

“If migrants are caught four hours to the west, they might be brought all the way over to Agua Prieta and dropped off there. So, oftentimes, migrants are really disoriented.” Many of the deportees arrive at Agua Prieta at 3:00 in the morning, shivering from the cold desert night.

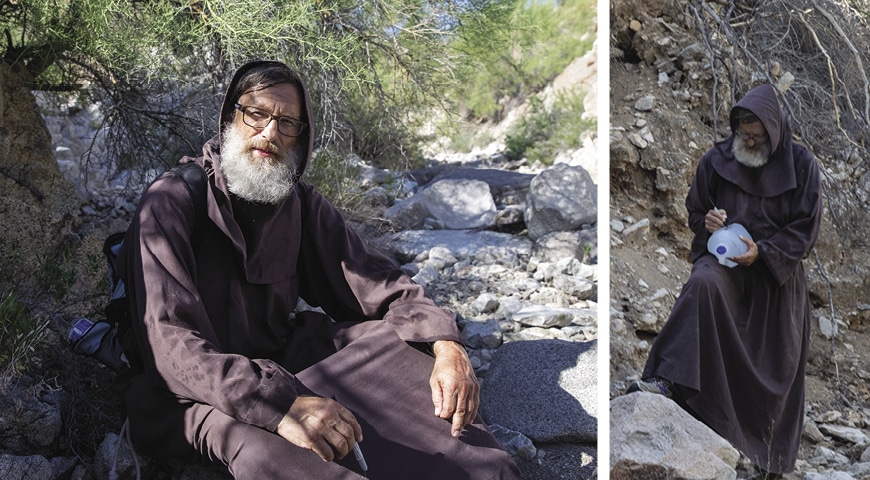

Brother David Buer, OFM, has worked at the US-Mexico border for over 15 years. Among other justice and peace initiatives, he assists at the Migrant Resource Center in Agua Prieta, Mexico. Photos: Octavio Duran, OFM

At the Migrant Resource Center (MRC) in Agua Prieta, those who have just been sent back can find food, water, coffee from the fair trade cooperative Café Justo, basic medical attention, and other resources. The center, which has been open since 2006, is a joint effort among the town of Agua Prieta, the Presbyterian Church’s Frontera de Cristo organization, and the School Sisters of Notre Dame and has helped over 100,000 people gain their footing after being deported from the United States.

Although the number of migrants passing through the center fluctuates, even on a slow night, Brother David has seen just how important it is for the MRC to offer its services. “One night a few weeks ago, only seven migrants came through, but they were so grateful,” he recalls. “One guy had been out in the desert for three days without food. We had hot coffee and sandwiches for them and two outdoor heaters for them to warm up next to.” As the seven migrants went on their way, they each thanked Brother David for being there for them. The next night, 85 migrants showed up at the center.

For Brother David, as with Sister Maria Louise, Franciscan spirituality continually injects energy into his work at the border. Although St. Francis lived in a world radically different from ours, “I think he’d be proud to learn that his friars are doing this kind of work in the world today,” he says. “As Franciscans, our focus is presence and direct service.”

For more about the MRC, visit Frontera de Cristo’s website: FronteradeCristo.org/Ministries.

1 thought on “Franciscans at the Border”

Pingback: One Nation Under God - Catholic Daily