He’s known for his Mafia epics and dark character studies, but this legendary filmmaker has a profound spiritual side, as witnessed by a trio of challenging movies about faith.

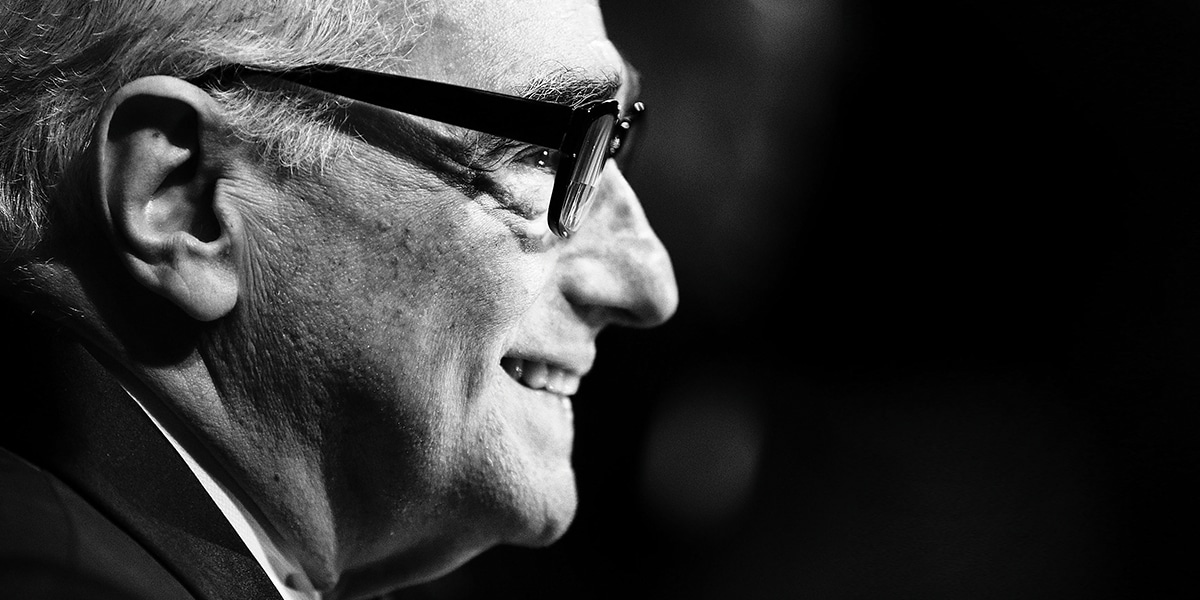

When you think of the phrase Catholic art, images of Renaissance paintings or marble statues might come to mind. But when you hear or see the name Martin Scorsese, Catholic art is probably not the first association you would make. Famous for his Mafia movies (such as Goodfellas, Casino, and The Irishman, which premiered at the New York Film Festival this past September), you might be surprised to learn that one of his lifelong ambitions was to complete what’s been dubbed his “faith trilogy” of films: The Last Temptation of Christ, Kundun, and Silence.

All three films are deeply rooted in a particularly Catholic sensibility and perception of the world. There’s even a term for this uniquely Catholic approach to the arts: “the Catholic imagination.”

To understand Scorsese’s distinct take on the Catholic imagination, though, you don’t need to read volumes on Catholic aesthetics or scholarly articles on his work in film journals. A look at his upbringing in an Italian American, working-class, Catholic family in New York City sheds more light on the roots of his artistic development than any academic research could provide.

Life on the Mean Streets

At the 2017 Catholic Media Conference (CMC) in Québec City, Canada, Scorsese sat down for a Q&A session with Paul Elie, director of the American Pilgrimage Project and frequent contributor to the New York Times, following a screening of Silence. Members of the Catholic press, including St. Anthony Messenger, were treated to an hour-long conversation between the two, as they discussed Silence, spirituality, and his decades in the film industry.

The conversation kicked off with the director talking about his upbringing in New York City. Born in 1942, Scorsese lived his first seven years in a comfortable house in Queens—”the suburbs,” as he called it. After falling on hard economic times, the Scorsese family had to relocate to a cramped tenement apartment in Little Italy. “I was thrown into this world, which was a street world, butcher shops—two on each block—grocery stores, almost like a thriving medieval village,” Scorsese recalled. “The block we lived on was mainly Sicilian, and one block away was skid row,” a frightening place where the criminal element loomed large. His parents, Charles and Catherine, were devout Catholics who worked hard as a clothes presser and seamstress to provide for their family.

Set in stark contrast to the hustle and bustle was Old St. Patrick’s Cathedral (now a basilica). “The mood in the church itself is something very peaceful,” Scorsese said. “The power of the church was as a sort of balm,” an oasis from the dangerous world outside.

At Old St. Patrick’s, Scorsese was an altar boy and often served at the Saturday morning Mass for the Dead. In the ritual movements, colorful stained glass windows, and incense rising heavenward, a young Scorsese observed the theater-like production quality of weekly Mass.

A young parish priest with a love of the cinema, Father Frank Principe, encouraged Scorsese and his classmates to engage with art as part of their intellectual and spiritual development. This certainly took root in the young Scorsese, who would later attend New York University to study film. Scorsese quickly rose in the ranks of the film industry, making short student films, working as an assistant director and editor on the documentary Woodstock, and finally making feature films such as 1973’s Mean Streets, set in the Little Italy he knew so well.

After making arguably one of the best films of the 1980s (Raging Bull), Scorsese’s reputation as an auteur was seemingly solidified. But the clarity of Scorsese’s moral vision and even his worth as a filmmaker would be called into question when he made a film that challenged audiences with some considerably weighty subject matter: the humanity of Jesus.

A Film and a Firestorm

When a film studio executive asked Scorsese why he wanted to make The Last Temptation of Christ, he responded, “So I can get to know Jesus better.” The idea of making the film goes all the way back to 1972, when Scorsese read Nikos Kazantzakis’ fictional retelling of Jesus’ life, ministry, and crucifixion. After a long gestation and a canceled production in 1983, The Last Temptation of Christ was released in August 1988. Much controversy had already been simmering for the months leading up to its release after a leaked—and unfinished—script came to the attention of Christian leaders who were outraged at the film’s premise.

In The Last Temptation, Jesus (Willem Dafoe) is shown to be a man who is occasionally unsure of himself and besieged by temptations. The title refers to Satan’s final attempt to lure Jesus in while he is dying on the cross. In a lengthy sequence near the end of the film, Satan—under the guise of a little girl who says that she’s Jesus’ guardian angel—shows Jesus what his life could be like if he simply came down from the cross and submitted to his will. Jesus is promised a long, happy life where he is married to Mary Magdalene (Barbara Hershey) and raises a family. Ultimately, and in keeping with Scripture, Jesus refuses the temptation and dies on the cross, fulfilling his sacrifice for humanity.

In Scorsese on Scorsese (Faber and Faber), a compilation of interview transcripts edited by Ian Christie and David Thompson, the director says, “I believe that Jesus is fully divine, but the teaching at Catholic schools placed such an emphasis on the divine side that if Jesus walked into a room, you’d know he was God . . . instead of being just another person.” Indeed, two of Jesus’ own disciples failed to recognize him on the road to Emmaus (Lk 24:13‚ 35).

The pushback to the film was strong, including protests and several movie theaters that refused to show it. Evangelist and founder of the Campus Crusade for Christ, Bill Bright, even offered to buy the negative of the film from Universal Pictures for $10 million, with the intention of destroying it so that it would never see the light of day. Ironically, as Scorsese pointed out during his Q&A with Elie, many of the film’s harshest critics hadn’t actually seen it. “I had done The Last Temptation of Christ, and we had to screen it for all the people who were complaining about it who hadn’t seen it yet,” he recalled. Among those at the screening were various evangelical leaders, Catholic clergy, and Bishop Paul Moore, head of the Episcopal Diocese of New York. Bishop Moore approached Scorsese after the screening and told him, “The film is Christologically correct,” referring to the Council of Chalcedon in 451, when Church leaders affirmed the idea that Jesus is both fully human and fully divine.

Despite all the controversy, Scorsese was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Director for his work on the film. Years after the film’s release, a priest friend of his told him that some seminaries even include Kazantzakis’ book as a supplemental text and conversation starter. No matter what one’s feelings are about The Last Temptation of Christ, Scorsese succeeded in opening up a discussion about Jesus in a world that was—and still is—becoming more secular. But his interest in making films about faith didn’t end there, and his next project would take him far from his comfort zone as a storyteller rooted in Western culture.

Parallels in Faith

One year after the release of The Last Temptation of Christ, Scorsese read a script written by Melissa Mathieson about the early life of the Dalai Lama and was instantly committed to making the film. He spent two days with the Dalai Lama at Mathieson’s Wyoming ranch in 1993, getting to know him and the plight of the Tibetan people better. By the time Kundun was released in 1997, “a lot was changing in my life,” Scorsese recalls. Filming wrapped up just before Christmas 1996, and he went to spend time with his dying mother. “She died on January 6 [1997], almost as if she had been waiting until I got back,” Scorsese says. “I dedicated the film [Kundun] to my mother, because the unconditional love that she represented to me in my own life somehow connected with the idea of the Dalai Lama having a compassionate love for all sentient beings.”

Kundun traces the Dalai Lama’s life from 1937 (when he was discovered by monks to be a promising candidate at the age of 2) to 1959 (when he escaped to exile in India). Lending a sense of realism, many Tibetan cast members were untrained actors who knew intimately their people’s stuggle against Communist China. The film depicts the steady encroachment of China—under the harsh regime of Chairman Mao Zedong—and its eventual hostile takeover of Tibet in the 1950s. One of the most chilling scenes occurs when the Dalai Lama (played as a young adult by Tenzin Thuthob Tsarong) meets with Chairman Mao (Robert Lin) to discuss Tibet’s future. Though seemingly polite and pleasant, Mao lectures the Dalai Lama that “religion is poison” and that Tibetans are “poisoned and inferior” because of their beliefs. A stoic and compassionate Dalai Lama refuses to return the vitriol and instead, as our own faith calls us to do, turns the other cheek.

There are some striking parallels between Kundun and The Last Temptation of Christ. Both Jesus and the Dalai Lama speak truth to power nonviolently and with hearts full of compassion. The two also have been charged with an awesome responsibility—Jesus must embrace his role as the Messiah, and the Dalai Lama takes on the mantle of the incarnation of the Buddha of compassion and leader of the Tibetan people.

Kundun also met with controversy, this time from a nation of over a billion people—China. The Chinese government pressured the Walt Disney Company by threatening the company’s future access into their lucrative market. When Disney pushed back and went on with the scheduled release in December 1997, China pulled Disney cartoons from their airwaves and banned all Disney movies from being shown. They even issued lifelong bans on both Scorsese and screenwriter Mathieson.

Despite this hostility to the film on the part of the Chinese government, Kundun garnered critical acclaim and four Oscar nominations. It’s a film that warrants repeat viewings, as there is much for Westerners and Christians to absorb. “As a Christian, I really believe that the future of being human is love and compassion. . . . And I see these people [Tibetan Buddhists] practicing this belief,” the director reflects in Scorsese on Scorsese. “Ultimately, [Kundun] is about religious experience. . . . For me, it was about giving a gift back to their culture, putting together the beauty and compassion that they represent.”

Scorsese could have stopped his exploration of faith through the medium of film with the powerful duo of Last Temptation and Kundun. But a chance book recommendation from 30 years ago planted the seed for the third film of his faith trilogy.

Getting to the Heart of Faith

In 1988, after the screening of The Last Temptation of Christ for various Christian leaders, Scorsese got together with Bishop Moore and a priest friend for dinner and a three-hour conversation on Christianity and faith. The bishop gave Scorsese a book, telling him to read it and then “define what faith is.” That book was Silence, by Shusako Endo, a Catholic author who has been called “the Graham Greene of Japan.” After finishing it, the director knew right away that he needed to make a film adaptation.

Finally released in December 2016, Silence follows two fictional 17th-century Jesuit missionaries, Father Sebastião Rodrigues (Andrew Garfield) and Father Francisco Garupe (Adam Driver), on their journey to Japan. Training for the film was rigorous—both physically and spiritually—for the two actors. Both lost significant weight for their roles and were also given a crash course in Ignatian spirituality by the film’s Jesuit adviser, Father James Martin.

The priests’ mission is to spread the Catholic faith and track down their mentor, Father Cristóvão Ferreira (Liam Neeson), who is suspected of renouncing his faith after being tortured. When they arrive in Japan, the two priests are horrified by what they see. The small Christian community is heavily repressed and forced to practice its faith in secret. Father Ferreira has not only apostatized (rejected the Christian faith) but has also taken a Japanese name and is now married.

Eventually, both priests are captured by Japanese authorities and suffer two very different fates. Father Garupe is executed by drowning, while Father Rodrigues is imprisoned, repeatedly tortured, and asked to reject his faith by stepping on an image of Christ, called a fumi-e. Father Rodrigues finds out that his resistance to apostasy is actually prolonging the suffering and causing the deaths of the Japanese Christians he came to serve. When Father Rodrigues is brought once more before the fumi-e, he hears an inner voice of Christ tell him: “Come ahead now. It’s all right. Step on me. I understand your pain. I was born into this world to share men’s pain. I carried this cross for your pain. Your life is with me now. Step.” Father Rodrigues apostatizes and later, like Father Ferreira, marries a Japanese woman.

At the end of the film, it’s revealed that Father Rodrigues never actually gave up his faith. After he dies, he is shown in a traditional round Japanese casket, a small wooden crucifix given to him by a Japanese Christian many years earlier clutched in his hand. The implication is that his wife or some other loved one placed it there. Although Silence was only nominated for one Academy Award (Best Cinematography), it received the most critical acclaim of his trilogy of movies on faith. Scorsese even got to show the film to about 300 Jesuits at the Vatican and had a private audience with Pope Francis afterward.

In his homily during morning Mass on January 29, 2018, Pope Francis said, “There is no humility without humiliation.” In his Q&A with Scorsese, Elie connected this very quote to the character of Father Rodrigues and how the priest’s idea of martyrdom is slowly dismantled. All that remains is the question of what faith really is. In his response, Scorsese pointed out: “[Father Rodrigues] keeps equating his journey to Christ’s. It’s his own Calvary, the whole story. And that’s got to be knocked down.”

For Scorsese, making Silence forced him to reflect on the fundamental questions of what it means to be a Christian and how to live like Christ in a hostile world. In his conversation with Elie, the director framed the struggle this way: “How does one live a life that is, in my case, [according to] a Christian ideal in a world where there is a lot of evil?” How we answer this question points to the very core of our Christian identity.

For the Love of the Story

At 76, Scorsese is showing no signs of slowing down, as witnessed by his two releases this year: a documentary on Bob Dylan (Rolling Thunder Review) and The Irishman. As he told Elie in their interview, “The constant [in my life] is this crazy desire to tell stories with pictures that move.” The Irishman, which features an all-star cast including Robert De Niro, Anna Paquin, and Al Pacino, is a return to the criminal underworld for the director and revolves around the story of labor union leader Jimmy Hoffa. But based on the passion and energy he brought to his faith trilogy, one can’t rule out the possibility of Scorsese revisiting religious themes and spiritual questions on-screen.

Faith is often a struggle, even or especially for the most devout. By engaging art that challenges our notions of religious truth and moral tenets, we’re given the opportunity to either solidify our stances or adopt new ones that help us grow along our path to understanding and deeper belief. If we allow ourselves to be challenged by movies such as the ones that make up Scorsese’s faith trilogy, we might find ourselves contemplating some pretty deep questions—and ones that will lead to an even deeper faith.

Father Principe and the Sanctuary of the Cinema

Diagnosed with severe asthma at the age of 3, Martin Scorsese couldn’t play sports with the other neighborhood kids or even laugh too hard, as that could trigger an attack and a hospital visit. This, along with the criminal element on the streets, limited what Scorsese could do with his time as a child. With his natural curiosity, proclivity to observe things closely, and burgeoning creative spirit, Scorsese found the movie theater to be a logical place to pass the time. It, like Old St. Patrick’s, was also a refuge.

Most of the older priests focused their outreach on the older parishioners, especially those who had emigrated from the Old World. “Nobody was talking to the kids growing up on the mean streets,” Scorsese remembers. But a young, energetic priest named Father Frank Principe did. He played records of classical music for the seventh- and eighth-grade students, encouraged them to read authors such as Graham Greene, and even took them to the cinema, engaging students afterward in conversation and critique about the movie they just saw.

The priest was such a strong influence on Scorsese that he even briefly considered the priesthood before realizing that his vocation was to be found in the arts. Scorsese and his priest mentor didn’t always see eye to eye on art, and Father Principe once leveled this famous critique of the filmmaker’s work: “Too much Good Friday, not enough Easter Sunday.” But Father Principe left a lasting impression on his prot ég é: the importance of looking at film through a moral lens.

Catholicism and the Experience of the Arts

In his book The Catholic Imagination, Catholic priest, author, and sociologist Andrew Greeley helped popularize the notion that there is a faith-based creative sensibility that “sees created reality as a ‘sacrament,’ that is, a revelation of the presence of God.” Indeed, the seven sacraments are often depicted or referred to in the arts, whether in paintings or in motion pictures. Examples abound in the medium of film—from Baptism in The Godfather, to the Eucharist in Romero, to Reconciliation in The Exorcist.

“[The] statues and holy water, stained glass and votive candles, saints and religious medals, rosary beads and holy pictures” we encounter in the Catholic world hint at “a deeper and more pervasive religious sensibility which inclines Catholics to see the Holy lurking in creation,” Greeley writes. He provides numerous examples of it in the arts—from Michelangelo to Flannery O’Connor. But he also points to Martin Scorsese, whose films “are the quintessential illustrations of the use of the Catholic sense of community and Catholic symbols in American filmmaking.”

Greeley points out that a strong sense of community, especially for immigrant Catholics and their families, is a crucial element of the Catholic imagination. “The neighborhood, with its often intense and sometimes limiting relationships, was the place where many Catholic immigrants worked out their adjustment to urban life in America, the space in which their Catholic view of human networks found an appropriate social form,” he writes.

Scorsese, with his upbringing in a tight-knit Sicilian family in New York’s Little Italy, would likely agree.