A former military chaplain explains how St. Francis can be an example for those struggling with the traumas of war.

St. Francis is usually portrayed in a docile fashion: a haloed figure gazing mildly at a bird perched on his hand with deer and rabbits gathered at his feet. But the dime-a-dozen garden statues miss the true character of the saint from Assisi. Francis, the patron of peace, was a man who had been through war and captivity and still carried mental wounds from the trauma.

These military experiences have drawn a unique crowd of devotees. Many veterans have been drawn to St. Francis’ example and comforted in their own trials by what they see as a kindred spirit.

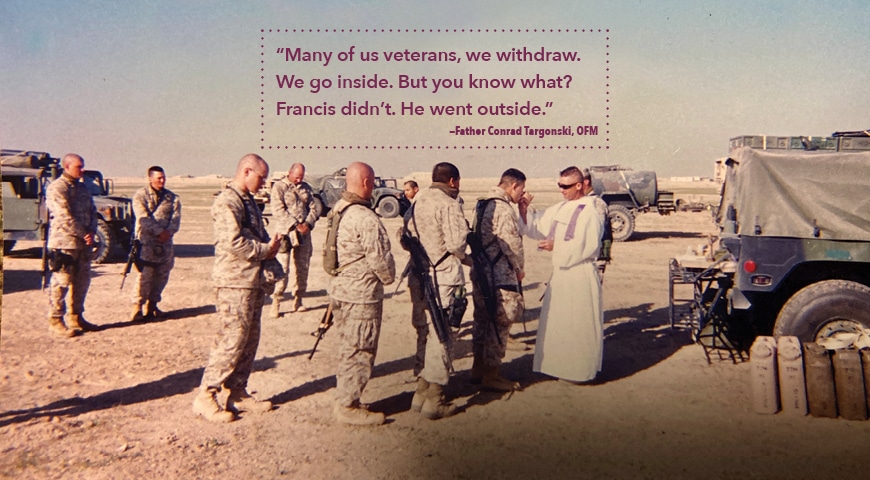

“He had the memories. He had the dreams. He had the flashbacks,” says Franciscan Father Conrad Targonski, himself a veteran. “And you think about these veterans and all the work I do with my brothers and sisters who are coming back from war; all of us feel the same way.”

After serving for 22 years as a chaplain for the Marines, he now ministers to students at Wisconsin’s Viterbo University. He says that veterans of all ages still come to him for spiritual guidance, and he regularly takes these military men and women on pilgrimages of healing.

Francis, the Veteran

Long before St. Francis would hear the voice of Christ and renounce wealth for a life of poverty, he lived the privileged life of a young aristocrat. When war broke out between Assisi and the neighboring city of Perugia, he eagerly signed up. The young man, then in his early 20s, yearned for the romantic glory of war, not unlike many young enlistees today.

“When Francis went to war, he realized it wasn’t what he thought,” says Father Targonski. “It was a real startling experience; [like] when a young person walked on to, let’s say, the Marine Corps, and he wanted to be a Marine and all these billboards that kind of espouse the Marine ideal. Then he meets the drill instructor.”

Rushing into battle without any training, Francis was captured by the enemy. He likely saw the tragedy unfold as his fellows from Assisi, who were vastly outnumbered, were slaughtered in a crushing defeat. Other prisoners were immediately put to death, but the men of Perugia realized that this young aristocrat might carry a valuable ransom and threw him into prison.

Francis was held in miserable conditions for a year while his enemies negotiated the price of his head. Eventually, his father paid for Francis’ freedom, though some accounts detail that he had already contracted a grave illness from inhumane treatment. Looking deeply into writings from his day, some analysts say that, long after his conversion, Francis would still experience post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) from this battle and imprisonment.

“In some of the writings, it’s very strange. He’s with the brothers already, and he wakes up in the middle of the night feeling rats crawling all over him, and he’s yelling,” says Father Targonski.

Though it’s not a nightmare that would be expected from the patron saint of animals, it’s one that military veterans can deeply relate to. It is also one of many stories of St. Francis that has helped Father Targonski through his own trauma.

“Sometimes it’s difficult, [and] some days are worse than others. But I saw a lot,” says Father Targonski.

Ministering in War

During his time as a military chaplain, Father Targonski served two tours in Iraq. The Chicago native was deployed with the Seventh Marine regiment during the Battle of Fallujah, which, in 2004, retook the city from Islamic insurgents and resistance fighters. The battle would be one of the bloodiest of the war, with 110 coalition forces and thousands of civilians killed.

Some 3,000 insurgents were also killed or captured. The Marines fought into the heart of the city itself—an environment where a concealed sniper, an ambush, or a booby trap could be around any corner.

As supervisory chaplain and the only Catholic priest, Father Targonski had to hurry through the streets from unit to unit and minister to the 14 other chaplains.

“You were seeing bombs. We called them tracers. You were constantly taking cover of mortars flying into your position. It’s the only place you’d be bored and five seconds later you go to utter terror,” he recalls. “I see on the news bodies lying in the streets, but here I was seeing them right before my eyes.”

In Fallujah, Father Targonski carried with him a replica of the San Damiano cross, the image that would mark the turning point of St. Francis’ life. It was this icon—a striking portrayal of Christ on the cross, eyes open and seeming to be already victorious over death—that Francis was praying before when he heard the voice of Christ ask him to “rebuild my church.”

“That was my sword, and I just gazed at it,” says Father Targonski, adding that he now has a great devotion to the image.

The Veterans of the San Damiano Cross

After hearing the words of Christ while kneeling before the San Damiano cross, Francis would take some of the most radical steps of his life. First, he would sell his father’s goods in an attempt to fund literal repairs of the chapel where the crucifix hung. Then, once discovered and rebuked by both his father and the local bishop, he would renounce his birthright, embrace poverty, and return everything to his father—even the clothes on his back.

But what was it about this now-famous icon, then dirty and surrounded by a crumbling edifice, that caused such a radical change in the aristocrat-turned-saint?

“There are three military people in the icon,” Father Targonski points out. “[The San Damiano cross is] actually talking to veterans coming back from war.”

Unremarked by most, yet unmistakable to a veteran’s eye, those three figures may have arrested the attention of the young man. In the icon, five large images of people are gathered around the crucified Christ, witnesses described by the Bible, including Mary his mother and the beloved apostle John. At the far right is the Roman centurion who had been stationed to guard the prisoner. His hand is raised as if he is just uttering the all-important profession of faith, “Truly this was the Son of God!”

At the feet of these larger images are two smaller figures—the soldier who pierced the side of Christ and the soldier who offered Jesus a sponge soaked in vinegar. Those military men, all turned toward the crucified Christ, may have shown the war-traumatized veteran where he should turn to find healing.

For Father Targonski, the image of Christ has helped heal some of the worst memories of the war. Once he saw a flatbed truck filled with the elderly, along with women and children, roll into an active battle zone.

Running to the truck despite the firing around him, Father Targonski saw a young girl cover her eyes in fear. The eyes of Christ on the cross, he reflected, are open.

“They say that the eyes are the windows of the soul,” he explains. “I think Francis saw in the eyes the soul of Christ, which is divine mercy.

“It’s part of healing the memory. It’s that process where you look at things that were terrible, but you look and see good things that may have happened because of it,” he points out, “[like] saying what have I learned from this, and how can I make the world better?”

Following the Veterans’ Experience

Today, Father Targonski hosts a special pilgrimage for veterans that introduces them to St. Francis and follows his journey from the military to sainthood. The trip takes these men and women across the Italy that Francis knew, including Assisi and the city where Francis experienced war. They also journey to the fertile Rieti Valley, where Francis was overwhelmed by the glory of God’s creation.

There, near one of four shrines that he would eventually erect in that valley, Francis experienced what many veterans long for: the knowledge that he was forgiven.

“The stories are uncannily appropriate because he had this problem with not being forgiven. And that’s what veterans have. Sometimes they’re forced to kill, and sometimes they have to deal with things,” Father Targonski explains. “And Francis struggled. He struggled and he struggled with it. But something happened in Poggio Bustone, where he realized he was forgiven.”

Today, a modern statue representing God hovering over St. Francis commemorates this moment of mercy. Father Targonski says that the veterans on the trip are always “dazed” by it.

There is also another statue that unexpectedly captures their attention. This likeness, situated outside the Basilica of St. Francis in Assisi and often overlooked by civilian pilgrims, portrays the strongest connection to Francis’ former military life. Francis, unexpectedly garbed in full medieval armor, sits astride his armored horse. His head hangs down as if from deep sorrow.

The portrayal captures another key moment in the life of the saint that occurred after Francis had fought in Perugia, yet still before his conversion at San Damiano. He had left Assisi to join the Crusades, not unlike a soldier leaving for a second tour of duty.

Likely he was still grappling with the emotions of his first battle and felt the need to redeem the memory by a second trial. This time, he had prepared himself by purchasing the best armor that the age could provide. Perhaps he again was struggling with his desperate desire for the glory of knighthood.

Long before reaching the battle, however, the would-be Crusader heard the voice of Christ. The Lord stopped his progress and instructed Francis to serve “the master,” not the man. When Francis asked what he must do, God answered: “Go back home. It will be revealed to you what you must do.”

The dejected figure immortalized by the statue captures how Francis must have felt on his long journey back to Assisi. Still unclear what God wanted from him and unable to explain what has happened, the young man fears the imminent reaction of his family and friends at this early, inglorious homecoming.

It’s another experience that speaks deeply to the military vet. First, there is the confusing jolt back into civilian life. Then, it’s the fear of what others will think as the veteran attempts to process his or her unexplainable experience.

“With a veteran, you’ve got that call to adventure,” explains Father Targonski, “then you face reality, and then, of course, you have this fact that you almost died, and your compatriots have died.

“Even friars mentioned that I was different, and I think they were afraid of me, not because I was scary, but they didn’t know how to talk to me,” he recalls. “It’s just something that I think many of us experience when we come back to our families. Wives are afraid. Children are afraid.”

Looking Outward

So the veteran, like the literal portrayal of Francis, figuratively lets his or her head droop low in sorrow. In response to a world that does not understand their experience, these warriors-turned-civilians tend to withdraw. But instead of finding healing within, many experience greater depression and anxiety, and even lose hold of their former relationships.

Yet, here again, these men and women can find hope and inspiration in the example of St. Francis.

“He did something very extraordinary,” Father Targonski points out. “Many of us veterans, we withdraw. We go inside. But you know what? Francis didn’t. He went outside.”

After his figurative “defeat” en route to the Crusades, Francis looks outward to literally embrace others. Riding around the outskirts of Assisi, he comes upon a leper—an outcast shunned by the rest of the town, dirty and horribly disfigured by the ailment.

After all of his searching for a purpose beyond his own traumatic experiences, the young saint realizes that their shared suffering has made this leper his kin. He embraces the man and kisses him in a rapture of brotherly love. In that moment, he seems to understand that God can use his darkest experiences to bless those around him.

“Francis was commissioned; he used his experience to heal. And I think that’s why he continued with the lepers. He went outward,” Father Targonski says. “We have homeless shelters here in La Crosse, Wisconsin, and that’s where I hang out. There’s a certain solidarity that I feel. That’s where we belong.”

In the years that followed, Francis would continue his outward focus to preach the Gospel in distant lands, undaunted by danger and imprisonment. He had finally found that his yearning for glory was not an earthly one, but one directing him to reach heaven itself.

Working for Peace

Francis’ radical way of life quickly attracted other veterans who were, like himself, in search of both glory and healing. Accounts detail that on his second missionary journey, Francis met a soldier in the street, Angelo Tancredi, and called him to become a soldier of Christ. According to The History of St. Francis of Assisi by Léon Le Monnier, the saint said: “My brother, thou has long worn belt, sword, and spurs; henceforth, thy belt must be a cord, thy sword the cross of Jesus Christ, and for spurs thou must have dust and mud. Follow me.”

Angelo immediately followed him, giving up everything to become a friar. Father Targonski notes that even the very first person to join the brotherhood was himself a soldier.

“[Francis’] best battle buddy, Bernard of Quintavalle, joins him. That’s what began it all,” says Father Targonski, quickly adding the obvious questions: “How many other combat veterans joined Francis? How many of these guys were at war? And why were they changing to such a radical, different type of life?”

Perhaps Francis’ very patronage of peace began on the battlefield. After all, who would be more motivated to work for peace than one who had experienced the horrors of war and suffered from the trauma for the rest of his life?

“Would we have the same Francis if he had not gone to war and had this experience of PTSD?” Father Targonski wonders. “I don’t know. But I think God uses experiences.”

God seems to be still using the experiences of St. Francis to touch others, especially those who, like him, have been on the battlefield.

“I’m a little prejudiced here: I think that veterans are going to change the world, and they see a world of harmony and fratelli tutti,” says Father Targonski, using the Italian phrase for “all brothers” that was coined by St. Francis and used by Pope Francis as the title of his most recent encyclical.

Even after leaving the field, the memories of war remain for the rest of a veteran’s life. But as the saint of peace has shown, the grace of God can transform even the worst experiences for his glory.