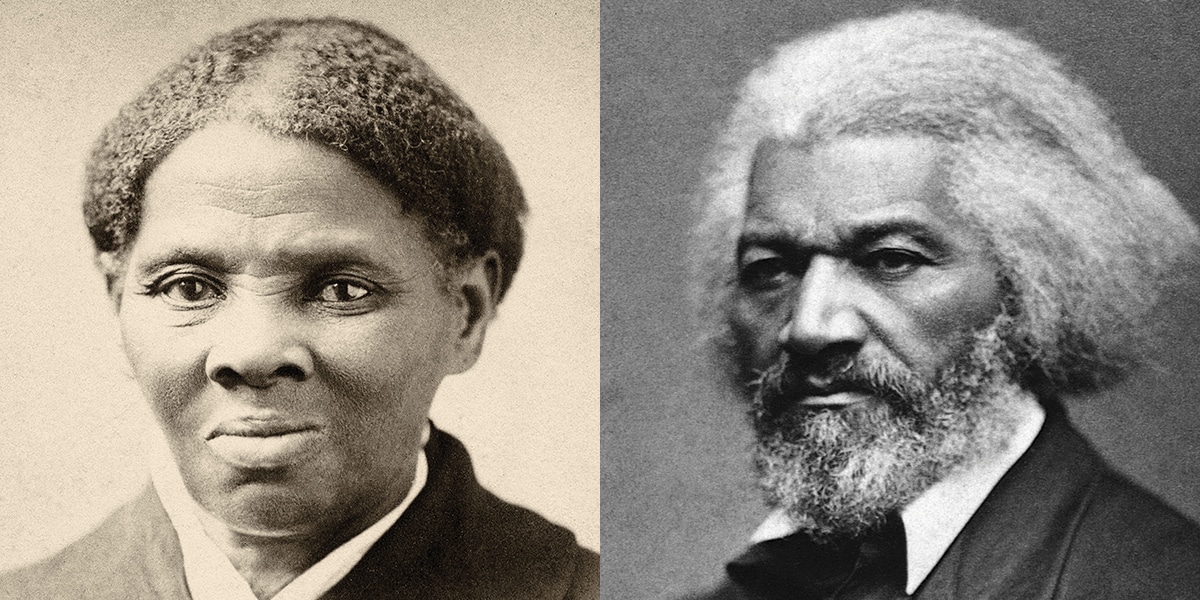

Harriet Tubman: Visions of Freedom

(PBS, check local listings)

“I have heard their groans and sighs, and seen their tears,” Harriet Tubman once said of enslaved people. “And I would give every drop of blood in my veins to free them.” This was no wishful thinking: Though the precise number Tubman freed is debated still, historians agree that she rescued around 70 people over the course of 13 trips on the Underground Railroad.

But this latter-day Moses (her code name during night raids) had an interior life that was just as rich and complex as her public one. And in PBS’ absorbing documentary Harriet Tubman: Visions of Freedom, we are given a substantive, three-dimensional glimpse into an American legend.

Born Araminta Ross in Maryland, a slave state, in 1822, Tubman faced the same daily horrors and degradations enslaved people endured. One incident peppered her life for the remainder of it. After she refused to help an overseer subdue an enslaved boy in a general store, she was struck in the head with a metal weight.

Denied medical care despite a skull fracture, she would suffer “spells” or seizures often, but Tubman saw them as doorways to the divine: conversations with the God she loved. After she freed herself in 1849, she used her wits and geographical abilities (not to mention a pistol that she wasn’t afraid to brandish) to free enslaved people.

While the handsome Visions of Freedom doesn’t break a lot of new ground in its portrait of Tubman, in many ways it doesn’t have to. Sometimes a celebration of a noble life is more than enough. Tubman, a stubborn and stalwart revolutionary, has earned her rightful place in American history. It’s our duty to study it.

Becoming Frederick Douglass

(PBS, check local listings)

A contemporary of Harriet Tubman’s and fellow Marylander, Frederick Douglass’ journey to emancipation looked much different, but his life and his legacy are just as important.

Becoming Frederick Douglass, interestingly, opens with what we don’t know about the man—namely the year he was born. Sadly, neither did he. Estimates place his year of birth around 1818. Growing up enslaved but with a deep intelligence and curiosity, Douglass had to be covert in learning to read. Once he gained that ability, he took his first steps toward freedom. He eventually escaped the Maryland plantation and began a life as an abolitionist, writer, orator, and political leader.

Perhaps what is most impressive about Douglass is that he refused to savor his freedom in obscurity. He traveled, lectured, pestered, and prodded lawmakers to see reason. And he used his platform to criticize President Abraham Lincoln for, among other things, the unfair treatment of Black Union soldiers. That kind of grit and righteous indignation would be his trademark.

Douglass’ uphill climb, post-enslavement, was steep, trying to sell a concept that most of White America at the time wasn’t ready to buy: that (then and now) Black lives matter. All of God’s children, regardless of skin tone, are beloved. Douglass knew it in his bones.

Becoming unfolds like a flower at daybreak—a methodical and deeply affecting plunge into an extraordinary American life, as well as a thoughtful look at the sin of slavery. But no one said it better than Douglass himself: “I have seen the cruelty and brutality of slavery. I was a graduate from this peculiar institution, with my diploma written on my back.”

1 thought on “Cry Freedom: Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass”

What a beautiful coincidence to have come up on this today, on the feast day of Harriet Tubman in the Episcopal Church. May God bless all those fighters for equality and liberation, both then and now.

Black Lives Matter