In a city known for its relentless pace, St. Francis Friends of the Poor offers a sanctuary where time slows and healing begins.

It was “one of those mornings.” Just moments before her interview with St. Anthony Messenger, Christina Byrne was dealing with a situation in the halls of Residence II on West 22nd Street in New York City. A worried resident had bolted downstairs to the front desk and shared that his neighbor was naked, screaming at someone who wasn’t there, and frantically moving all his belongings into the hallway.

Byrne, the executive director of St. Francis Friends of the Poor (SFFP) since January 2020, had grown accustomed to these “episodes.” The scene, in fact, proved the opposite of what someone might think. It was actually a window into how the model of SFFP was working—that’s right, working: an example of communal living and the spirit of radical acceptance and nonjudgment that prevails as residents are mutually connected through the suffering they share.

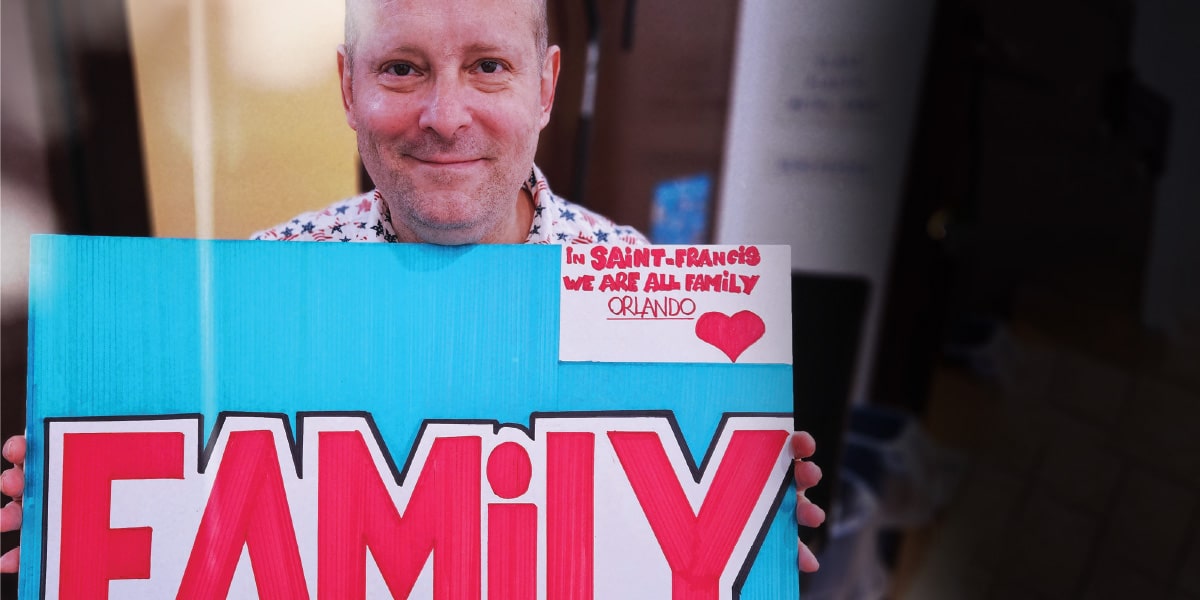

“The culture really becomes more than fraternal here—it’s familial,” Byrne says.

Had an episode like this unfolded in a standard apartment complex or neighborhood, it’s likely the first response would be to call the police. Understandable, but not all officers are trained to de-escalate or effectively assist people experiencing a mental health emergency.

But at SFFP, which has offered permanent supportive housing services to homeless men and women living with serious mental illness for 45 years, the residents have a mutual understanding of each other’s afflictions. There was no judging the naked man screaming at an invisible enemy. His neighbors knew what it was like to have a “bad day,” a psychotic break, or feel trapped in one’s head.

The person was not the problem, his neighbors knew. He just needed a little help, which they, too, have needed and may need again tomorrow. They are a community of beautiful people embodying a relational attitude that flowed right from the Franciscan heart of the organization.

Three Friars and an Impossible Dream

In the mid-1970s, Franciscan Friars John Felice and John McVean were working the daily breadline at the Church of St. Francis of Assisi on West 31st Street in Manhattan; the breadline continues to this day. Though they believed in the importance of the breadline, they noticed a deeper problem.

The deinstitutionalization of people with mental illness throughout the ’60s and ’70s led to an influx of homelessness, as patients were released from psychiatric hospitals without sufficient support to take on their mental health conditions and navigate their lives.

Friars Felice, McVean, and another Franciscan priest named Thomas Walters began to dream. What if they could acquire a residence in New York City that could provide long-term, permanent housing for those who experienced chronic homelessness and mental illness? Their goal: Bring dignity and self-respect to the marginalized within the homeless population by providing them with a home.

It was a vision that seemed impossible.

“[The vision] was kind of based on the lives we lived in the friary,” Friar McVean shared in a 2017 organizational video. “That’s the kind of housing we provide. It just came naturally to us.”

In 1980, they purchased an old welfare hotel on East 24th Street (Residence I) that now has 85 rooms. St. Francis Friends of the Poor was born. In 1982, they did it again with a hotel on West 22nd Street (Residence II), which now has 90 rooms. And, in 1985, they did it again with a property on Eighth Avenue (Residence III), which has 80 rooms. It was a “just do it” attitude that has remained with the organization and continues as SFFP plans for Residence IV. “In their hearts, they are a bunch of hippies, defying authority on every single level,” Byrne laughs.

Their pioneering of what would now be described as a “housing-first model” attracted frequent media coverage from local journalist Gabe Pressman, and Friar Felice even made an appearance on Good Morning America. The trinity of friars worked closely with New York City Mayor Ed Koch to meet the city’s homeless problem head-on, standing behind him at press conferences as the city tackled this issue. SFFP became the city’s first known recognized provider of permanent supportive housing for people who experienced homelessness and chronic mental illness.

Friar Felice humbly shared in the 2017 video, “We were just three friars who saw something that needed fixing.”

How Did They Do It?

Byrne remembers working for Catholic Charities a decade before her tenure as executive director at SFFP. Her colleagues wanted to establish a housing-first model in Washington, DC, and were stunned to discover SFFP had already been doing exactly that for decades. They traveled to meet with the trio of friars—Felice, McVean, and Walters—to listen and learn. They wondered what so many wonder: How did they do it?

One might think that making chronic mental illness and homelessness a requirement for residents in single-room occupancy hotels with shared bathrooms would be a recipe for disaster. However, SFFP residents remain for an average of 18 years. Eighteen years.

The biggest barrier that SFFP’s demographic faces is often simply leaving the building, so Monday through Friday, SFFP brings social workers, nurses, psychiatrists, medical doctors, case managers, entitlement specialists, and financial advisors to the residential buildings. They also keep the front desk in each building open 24/7 in case any issues arise.

“It’s our job to earn their trust enough so that they will eventually want to receive some of the services,” Byrne says.

The organization’s approach to rent is also empowering to the residents. Rent for affordable housing cannot legally exceed 30 percent of a tenant’s income, but SFFP’s rent, on average, is $212. “The fathers set their own standard,” Byrne reflects. “Whatever rent they were charging 40 years ago is essentially the same rent we’re charging now.”

Today there is a push in big cities for more integrated affordable housing in which people facing similar struggles with homelessness or mental illness live among families and other working-class people. The goal is to de-stigmatize people who are facing mental health challenges and prevent them from being “othered” or even siloed, like in the days of mental health institutions. SFFP’s success, however, makes the case for the opposite. In integrated housing, there are more 911 calls and complaints, which can lead to more turnover and evictions, which then costs more money for affordable housing programs.

“We have never evicted someone for not paying their rent or for being a hoarder or anything like that,” Byrne shares. “We work with them, you know, with their illness to help them be the best person they can be. Having all these people living together, we would argue that the success of the model that we’ve had—and others who also have these kinds of older congregate care settings—is because everyone who lives in the building is sharing an experience. They all know that their colleagues and neighbors are going through the same thing.”

Another model SFFP’s success seems to challenge is the criteria- and performance-based model: Stay sober, get a bed; stay clean, get a meal.

“Relationships are a huge part of recovery,” adds Jessica Feldman, the director of quality assurance and strategic initiatives at SFFP. “When someone from the streets comes into a program and they’re asked all these horrendously personal questions with the expectation they should share everything because they are the ones being served, well, there’s a power differential there.”

Brother Adolfo Mercado, a friar interning at SFFP and carrying on the legacies of Felice, McVean, and Walters, discusses how he and SFFP staffers help to facilitate culture in each building. He recalls one resident sharing with him that a neighbor kept knocking on his door for money, and the resident didn’t know what to do. Brother Mercado listened to him, walked him through his anxiety, and helped him realize that the knocking was probably disruptive to his neighbors too. If the resident had called the front desk, no one would know it was him.

Small as this example may seem, it is an everyday conversation that shows SFFP’s attention to detail as staffers come alongside residents and walk with them through their day-to-day challenges. Residents tend to gravitate to the on-site friars, often garbed in their brown habits, to discuss spirituality or issues of the soul. “There could not be a more marginalized group than people who both have been serially homeless and living with serious mental illness,” shares Feldman. “The fathers provided something that most social service folks don’t: true, meaningful relationship and connection. I’m pretty much a devout atheist, but I don’t think SFFP could do what it does without its underlying faith-based history.”

Ripples into the Future

On July 23, 2023, one of the founding friars, Friar Felice, died after a long battle with Alzheimer’s. Residents, usually wary to leave their places of security, could be seen walking the roughly eight blocks to the Church of St. Francis of Assisi for the funeral to pay their respects—the very church where Friars Felice and McVean had worked the breadline and dreamed their dream.

No more than a year later, Friar Walters began making plans to retire after more than 45 years of service. And on December 19, 2024, one month after the initial interviews for this story, Friar McVean passed away. Each of the SFFP buildings held a memorial service for its residents. Brother Mercado recalls the experience: “Literally, one woman was crying and said, ‘He found me on the streets, and now I live here, thanks to him.’”

Following Friar McVean’s passing, Brother Mercado recalls walking through Manhattan when he received a phone call from a resident. “I need to meet with you,” she said. “I was kind of worried, like, ‘What’s going on here?’” he reflects. Brother Mercado went to the residence and was greeted by the “grandmotherly” person who had called him. She had been an SFFP resident for a long time. Sitting next to her was one of SFFP’s financial advisors. Brother Mercado sat down.

Just a few decades before this resident had been lost on the streets. Now this resident wanted to make a $3,000 donation in memory of Friar McVean.

“The impact that the fathers had,” Byrne shares, “not just on the people that they provided support to over the years, but every other person living with mental illness who now is able to get the support they need to live in the community safely because of them and the whole network that they created—in the city and around the country—is just overwhelming.”

Byrne, the first lay, non-Franciscan executive director in the organization’s history, seeks to guide SFFP into the future, animated by the friars’ vision, philosophy, and legacy. She remembers how the eulogy began at Father McVean’s funeral in January, with a quote attributed to St. Francis of Assisi: “Start by doing what’s necessary; then do what’s possible, and suddenly you are doing the impossible.”