He counseled thousands in New York and Detroit, and miracles are attributed to his intercession. In a few weeks, he will take the next step toward canonization.

Why did they follow him? Why did they line up by the hundreds on a Detroit sidewalk or in New York, day after day, patiently waiting their turn to talk with him? This man was deemed not sharp enough to be a diocesan priest. He tried again and barely made it to ordination as a Capuchin Franciscan priest, and then without license to preach or hear confessions. Yet the faithful came by the thousands to hear simple counsel from this ordinary man. “Be confident in your faith,” Solanus Casey would tell them. “Seek, and you will receive.”

On November 18, in Detroit’s Ford Field, the Catholic Church recognized this Capuchin Franciscan as Blessed Solanus Casey. Declaring him a saint seems only a matter of time—and one more sanctity-proving miracle. In the weeks before his beatification, we visited the Detroit center devoted to his message and memory. There we talked to ordinary folks and two Franciscan experts about the man about to be named Blessed Solanus.

What was his strongest trait? He had a reputation as one who had the biblical gift of healing, which is why many came to him. Capuchin author Father Marty Pable says that flowed from a deeper gift, his “confidence in faith.” Another Capuchin, Brother Richard Merling, assistant postulator for Casey’s canonization, says it was his compassion. We’ll get back to these friars shortly. But first, a little background.

Life of a Saint

The man we will know as Blessed Solanus was born Bernard (“Barney”) Francis Casey on a farm near Prescott, Wisconsin, in 1870. Within a few years his father, Barney Sr., moved the family to a newer, bigger house, described later in life by Friar Solanus, with tongue in cheek, as a “one-story mansion, about 12 by 30 feet.” (He was known for his sense of humor.) The big room was divided to accommodate all 11 of the Caseys at night—parents in one section, kids in the other. The snowbanks sometimes mounted as high as the gable roof, he later recalled, not atypical for country living in Wisconsin winters.

His parents were first-generation Irish Americans. From his parents, Barney picked up folk traditions, songs, and storytelling—and a deep piety—of the old country. He would hold these for the rest of his life, most notably his seemingly constant prayer, his gift for listening to people’s stories and connecting to them. Then there was his (debatable) talent for playing the fiddle.

In his religious family, Barney the younger found himself naturally devoted to the Blessed Mother. He loved his rosary. No doubt he prayed it every other Sunday, when his half of the family alternated going to Mass with the other, for lack of space in the horse and wagon.

Of his life on the eastern bank of the Mississippi River, he later wrote that he had “never seen a picture in Bible history or elsewhere so nearly like an earthly paradise.”

But there were hard times. After two years of failed crops, the family decided that 17-year-old Barney should head to nearby Stillwater and find work. He worked at the log booms, unjamming felled trees as they floated to mills downriver. Then he moved to Superior, Wisconsin, where he was a conductor on the streetcar—a new invention at that time. He fell in love with a young woman and proposed marriage, but her parents wouldn’t allow it.

Along the way, God was calling him in another direction. One day in 1891, it all came into focus in Superior. Barney had to stop his streetcar because a beating was taking place amid a crowd, blocking the tracks. An injured woman was on the ground; a drunken man threatened her with a knife until police arrived. Casey “saw this as a kind of microcosm of all the violence and anger in the world,” writes a biographer. He felt called to do something about it, something different with his life than operating streetcars. He sought counsel from his pastor and discerned his call. He would, in his words, try to make the world better by serving God as a priest. He was accepted at St. Francis Seminary of the Milwaukee Archdiocese.

One could go on, but here are the keys to Casey’s Milwaukee seminary experience: Classes were taught in German. He was Irish. Try as he might, he remained a poor student academically. And he had a noticeable rebellious streak. He was sent home.

God was still calling, though. His spiritual advisor recommended the Capuchins to him. At St. Bonaventure Seminary in Detroit, Casey’s holiness shone, but still there were classes in German. He didn’t do well with Latin, either. Due to his academic deficiencies, the order made use of the now-antiquated practice of ordaining him a simplex priest, without faculties to preach or to hear confessions. Today he might have been declined ordination.

In Brooklyn, his first assignment, he was eventually appointed to help the porter, the friar who answers the door and interacts with visitors on behalf of the Franciscan community. It was there at the door, in New York parishes for 14 years, then in Detroit for 30 years, that Casey would make his mark, counseling people and praying for their healing. Healing came to many.

A Legacy of Love

Casey personally interacted with thousands of visitors over his career. In fact, most of those had come to the Capuchin Franciscan monasteries specifically to talk with Casey, whose healing reputation had spread. Today, families keep living memories of him.

Visiting Detroit’s Solanus Casey Center one day in August of this year, Shirley Smitz tells the story of her miraculous life. “I had a deadly kidney disease when I was 6,” Smitz, now in her 60s, explains. After she had received six transfusions without remission, her mother, Mary Waters, came to St. Bonaventure to ask for Casey’s prayers.

Mary, now elderly, sits close by, occasionally nodding in agreement as Smitz continues: “After my mother returned to the hospital, there was a doctor’s examination. The doctors came out and said, ‘Mrs. Waters, your daughter is well. It’s gone!’ The doctors didn’t know how it happened.” There are hundreds of miraculous stories connected to Father Casey in Detroit.

“He was a very humble and simple man,” says Capuchin Brother Richard, “and people were very attracted to that. They knew that he was a man who had the gift of healing . . . not only physical healing, but spiritual and relational healing.” Physical healing didn’t always come, he adds—Casey was no magician.

Brother Richard tells the story of one woman—whose husband was in the hospital and too ill to come to the monastery—coming to ask Casey to pray for a miracle. She asked him if he would call her husband and pray with him. Casey agreed, and, talking with her husband, said, “I’m praying that you will have a happy death.” The woman was dumbfounded, says Brother Richard. “That’s not what she came for!” he says with a knowing grin. But the man died happy: “He was so at peace with the fact that he was going to die. He accepted it all.”

Are all of these stories really believable? Father Marty jumps in: “I think they’re very believable. Once you grant that his faith in God’s power, in God’s love, was so strong, nothing is surprising when you think about it. ” People were not always healed, Father Marty is quick to add—this is about God’s will for each of us. “But you always felt better; you always felt some kind of spiritual lift when you talked to Solanus.”

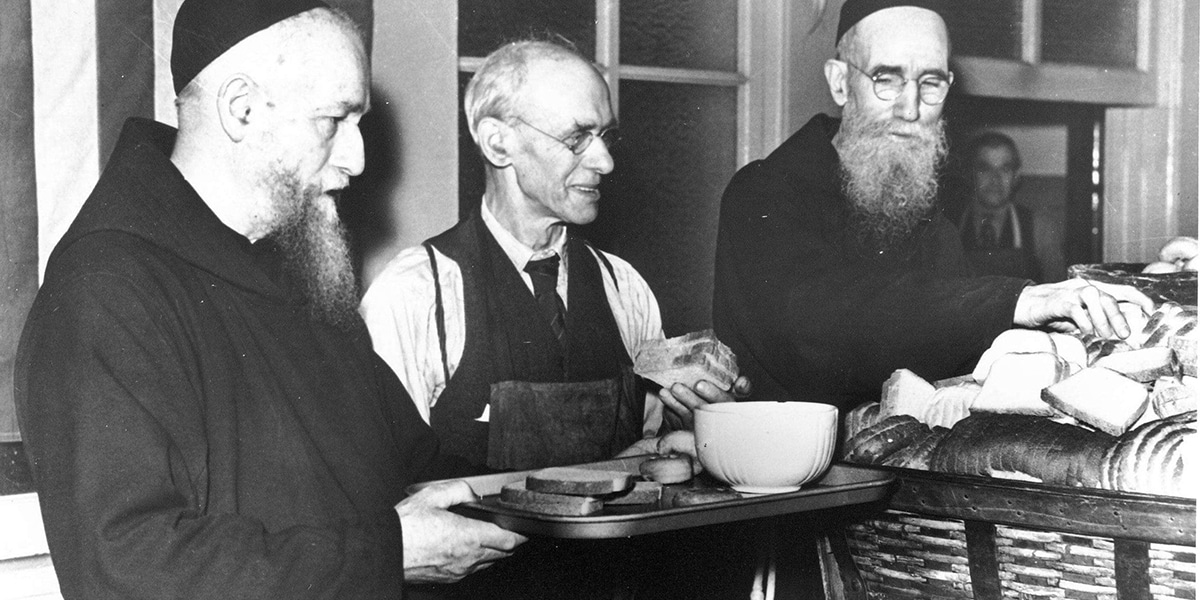

Feeding the Poor

Casey’s work at the door brought him in touch with people with every sort of need. As the Great Depression overtook the land in 1929, hungry people came to him for help. That was the beginning of a soup kitchen ministry that continues to this day.

In the beginning, he would give away some of the evening supper for the community, explains Brother Richard. “The cook would just be furious at that—you could understand it, in some sense,” he continues. “But Father Solanus had this sense that these people needed it.”

It wasn’t long before the Capuchin Soup Kitchen was established. There’s nothing like giving away someone’s supper to motivate action! “During the time of the Depression, they had close to four or five thousand people a day—they had lines going both directions down the block, around the corner on both ends,” says Brother Richard. The Secular Franciscans, a lay order founded by St. Francis, was strongly present, associated with the friars in Detroit. Urged by Casey and the other friars, they took it upon themselves to head out by horse and buggy to collect food from nearby farms and work at the kitchen.

Today there remain two soup kitchens. The original one, where the Solanus Casey Center is today, was moved a few blocks away from the monastery. Now it serves about 300 meals per day, says Brother Richard. The second location, closer to downtown, serves 1,500 meals daily. The kitchens provide an array of services—a story in their own right—in the spirit of Casey, who would say, echoing St. Francis himself, “I have two loves: the sick and the poor.”

Patience of a Saint

Casey was indefatigable, listening to people’s stories for as long as they needed to talk, praying with them well into the evening. It was a boon but also a challenge to his brother friars, especially as he went into overtime. The people “all waited their turn,” says Brother Richard, even waiting for Casey when other friars were available.

“There were chairs set up, and the biographies say nobody would seem to get upset because they knew that they would get the same attention.” The friars, in turn, were patient with the visitors, Brother Richard explains, then Father Marty jumps in: “Except the brother who was in charge at the front desk. He would say: ‘Casey, get a move on!’ ” Closing time was supposed to be 9 p.m.

Just as one might imagine a saint would do, Casey would then sometimes retire to the chapel “to pray a little.” Or he would answer the door before hours, early in the morning: “The other friars are too tired,” he said. In the middle of the night once, Casey met a drunken man at the door. “Where’s Father Solanus?” he demanded. “Why do you want him?” asked the priest. “I want to kill him!” the man said. “Well, we’ll need to talk about that,” said Casey, and invited the man in. As he sobered up, his story came out, and he sought confession. Casey insisted that he come back the next day to see a priest.” Tell him you’ve talked with me, and it will go quickly,” he added.

Casey’s work continued essentially till the end of his life. He had retired to St. Felix Monastery in Huntington, Indiana, but the people followed him. Father Marty, who lived there as a seminarian when Casey was in retirement, remembers that a box of letters would arrive daily, letters Casey would answer individually.

The once-quiet phone line was constantly ringing with requests to talk with the healing priest. But Casey would find time to wander around Huntington in the evenings, smelling the flowers, taking in nature, even harvesting honey from hives the friars kept. He died in 1957, at age 86, after several illnesses.

Today, interest in Solanus Casey is by no means limited to the places he lived. “Once he died, people started coming here and praying at his tomb, his gravesite, and felt that many wonderful things were happening,” says Brother Richard. Those people even come from countries afar. Healing services, up until recently held monthly at the monastery chapel, are now happening every two weeks.

Much of this renewed interest is related to the Solanus Casey Guild, which grew rapidly after Casey’s death to ensure he would be remembered. The drive that has promoted Casey’s canonization cause was part of that effort from the beginning. Brother Richard is the guild’s director. He says membership went from 60 members to 600 in its first month back in 1957, and kept growing. It had 100,000 members at one point, reports Brother Richard.

A Lasting Memory

Later this month, Father Marty and Brother Richard will look out at the crowd in Ford Field as bishops, cardinals, and Capuchins lead 60,000 in the beatification Mass. The day of festivity will be for something they have known all along: this man was a saint.

If Brother Richard had to say one thing that we could most imitate in Solanus Casey’s life, it would be his “compassion and understanding of other people.”

For Father Marty, it is Casey’s “sense of God’s presence and God’s goodness. I think that’s what Solanus tried to communicate to people. God is here, and he’s here for you. You can trust in God.”

Perhaps capturing some of Casey’s humor, Brother Richard imitates the holy man’s high-pitched, soft voice as the two friars recall, almost in unison, a refrain of Casey’s: “Trust in God; trust in God!”

Yet, “there’s nothing spectacular about him,” observes Father Marty. “He had no charisma at all! He didn’t preach, for one thing. He just had that gentleness, love, and compassion—people just sensed it; they were drawn to him.”

As Blessed Solanus Casey, even more will be.