Francis’ experience with loss illustrates a path to deeper relationships, including with God.

Be honest with yourself: How do you act when you’re sick or in pain? How would you feel if you lost everything? It is commonplace to grouse and complain. Equally common is to feel anxiety and fear. Some people become demanding of those around them, while others retreat into themselves, refusing help from anyone with an “I’m OK” attitude.

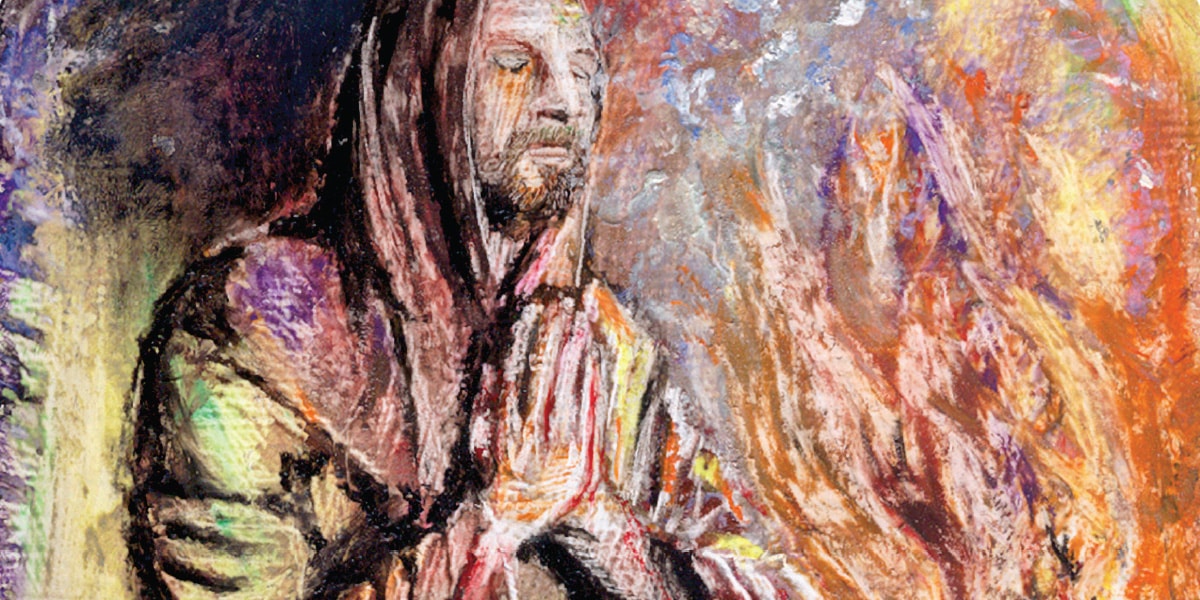

So, what would you do if, after experiencing years of chronic pain and diminishing eyesight, you found yourself depleted of all strength in a dank room surrounded by mice scurrying around? Francis of Assisi responded in a most particular way: He sang and wrote, “Praise to you, my Lord, with all your creatures.”

St. Francis reached out to all that surrounded him and felt comfort in the beauty of nature. He took special notice of each element of the world and reached out to praise God. Was this some form of spiritual bypassing? Overlooking and ignoring a difficult part of life and jumping to something pleasant? Or was this something more profound?

“The Canticle of Creatures,” composed by Francis of Assisi, is having a moment, as the saying goes—or really a year—as we celebrate the 800th anniversary of its composition this year. Composed in increments between 1225 and 1226, in the last year of Francis’ life, the canticle begins most famously by turning to the natural world as reason to praise God, before then turning to peacemakers and finally to death, all as reminders to us to give praise to our God. And he does so in a most intimate way, calling each element brother or sister: “Praise to you, my Lord, with all your creatures, especially Brother Sun.” Sister Moon and the Stars, Brothers Wind and Air, Sister Water, Brother Fire, and, finally, Sister Death are all named.

For many years, I had overlooked the complexity of these words and images. I admit that I have read them to be like all the nice families on TV—perhaps like The Brady Bunch of classic American TV—families who experience foibles and mishaps, but always make up by the end of the day. The wish for a happy ending is strong, but the reality of lived experience is usually more complex.

So is that sibling relationship.

When Fire Is Your Brother

I began to reconsider Francis’ understanding of sibling relationship with creation in January 2025 when the catastrophic fires in Pacific Palisades and Altadena, on opposite sides of Los Angeles, broke out and decimated lives. Of course, I have read about natural disasters many times: a devastating earthquake in Haiti, a hurricane named Helene that brought flooding in North Carolina, and more. I have watched video feeds from war-ravaged areas in Ukraine and Gaza. I have donated to causes and prayed for victims and recovery efforts.

But these fires in Los Angeles tore through two areas where I have lived. “Brother Fire” destroyed the houses I had once called home as he destroyed many people’s homes, businesses and livelihoods, churches and temples, schools, and libraries, along with so many people’s plans and expectations.

The relationship I have with those places has remained far more than mere thoughts or memories. Instead, I carry a visceral connection to people, and yes, also to trees, rocks, ocean, mountains, coyotes, and more. When I think of Altadena, I think of the families I lived with and can smell the pine trees that grew around the house where I lived—the house now reduced to rubble.

When I remember my year of housesitting in Pacific Palisades, I think of the crazy clan of roommates and can smell the eggrolls we made. And I can see the view of the ocean and feel the warmth of the sun that I experienced doing homework on the back porch of the house that recently burned to the ground. The fires have been a cause to reconnect with people I lived with: to share stories, catch up on our lives, and, most of all, to be there to offer support.

But seeing photos of both houses after the fires, I have cried often and felt deep, visceral sadness. How could a brother be so harsh as to bring such destruction to places and people I have loved?

I had been reflecting on the canticle when the fires forced me to realize that I am more practiced in studying the canticle as a piece of poetry and keeping its words at a tender distance than I am in living into its invitation of a deeper relationship: of sensing the world around me as close as my siblings.

What does this look like? Or more precisely, what does this feel like?

Francis’ Experience of Loss

The canticle was not composed in Francis’ youth, when he cheerfully embraced and cherished flowers and water, fire, and the moon. The canticle was stirring in his soul for many years—quite possibly after hearing the effusive praise of creation in the words of Daniel 3:56–57; 62–68; 75–81—but it is the labor of a spiritually mature Francis. He did not compose the song, or at least it was not written down, until he was able to let go completely of all that was separating him from true intimacy with God. This closeness with the Divine came through years of letting go, not just of material things, but of deeper personal attachments: his expectations and assumptions of how things should be, his privilege of social standing even within his order, and his control over his own body.

Francis’ conversion of faith had grown deeper as he aged and experienced both voluntary and involuntary loss. In 1220, when he relinquished leadership of his order, he did so sensing that he did not have the capacity to lead the growing fraternity of brothers. He had cultivated enough self-knowledge and self-awareness that he “retired” from leadership, thus allowing the movement to develop with different leadership.

If you have retired from work or let go of a project or way of life that is dear to you, you know that this letting go is not easy. We know from Francis’ episodes of anger and frustration with his brothers that he struggled with really letting go. We can often overlook how Francis could be so angry and petulant with his brothers when he disagreed with their behavior and when the order developed in ways he had not foreseen or wanted.

It can be more pleasant to consider the young, carefree “flower child” Francis in Franco Zeffirelli’s film Brother Sun, Sister Moon than the more complex Francis of his final years. But these tensions and conflicts he bore—both with his fellow friars and within himself—are also part of his life. After eruptions of anger, Francis would stop and regroup and let it all go, sensing the importance of the relationship over his expectations. This, too, is part of a sibling relationship.

Francis was sad and even disillusioned, leaving Rome after the approval of the Rule of 1223, a move that transformed his original, simple extraction of Gospel passages into a canonical legal document. So he found solace with the people of Greccio as he ventured back to Assisi. There, with the help of the townspeople, he recreated the Nativity scene to experience God in their midst.

Then came the final years of physical decline and painful treatments, when again he turned outward to relationships. He called to his fellow friars and his longtime friend and fellow caregiver, Lady Jacoba, to be with him as he died. For some of us these periods of our lives when we experience loss of any kind can be a time of reluctance and even depression, but for Francis, the final year of his life opened him up to deeper consolation and more profound faith as he was able to become more present with the beauty of the world around him and thereby his faith in Christ.

Here’s the simple (but not necessarily easy) truth of the Franciscan way: Letting go of attachments opens space for deeper awareness and visceral sense of the beauty all around us. This letting go is not a superficial acceptance of life’s events. Instead, it’s a deep awareness and acceptance of all that is interconnected.

Plum Village and Engaged Buddhism

Such a capacity of presence, awareness, and acceptance comes with significant contemplative practice that can be found in other spiritual traditions such as the Plum Village tradition of Zen Buddhism.

Thich Nhat Hanh (1926–2022), the Zen Buddhist monk and scholar who founded the Plum Village Tradition of Engaged Buddhism and the related Order of Interbeing, was a great admirer of Francis of Assisi. Like Francis, Thich Nhat Hanh (known affectionately as “Thay,” or “Teacher”) practiced and taught a simple way of being that can be readily misunderstood and made into a simplistic caricature much like that of St. Francis. But for those of us who practice either spiritual path, we know that the simple path is not necessarily an easy one.

Like Francis, Thich Nhat Hanh cultivated a spiritual practice of presence and awareness of interdependence through bitterly harsh experiences of war. Bearing witness to the grisly realities of violence in his homeland of Vietnam in the 1960s, Thich Nhat Hanh lived into a way of peace through self-awareness, knowing that if he let the violence that surrounded him enter his own way of being, his own capacity for inner peace would be destroyed and, with it, the possibility of peaceful resolution of any conflict, no matter how big or small.

Knowing that suffering grows in the distancing between people, Thay noted common forms of suffering, such as judgment, denial, avoidance, and resistance. Cultivating the capacity to be present with what is—all that is—without judgment, denial, avoidance, or resistance lies at the heart of Thay’s teachings and practice. Knowing that denial and pushing away lead to suffering, Thich Nhat Han practiced and encouraged others to practice curiosity to understand others. This includes awareness of our own judgments that are obstacles to deep and real presence to what is.

When one can let go of all the obstacles that tempt us—distractions, judgments, and any behavior that separates us from one another—we are able to cultivate and sustain relationships with one another and all of life that surrounds us. We sense the pain of another person, and we feel empathy. We see the beauty of a flower, and we feel delight. We find ourselves in relationships of interdependence or, as Thich Nhat Hanh often said, in “interbeing,” so our experiences are shared and not held at a distance. The relationships we maintain with one another and with our world become central to our being.

We “inter-are,” according to Thay.

Living the Canticle

More than just thinking about the sibling connections Francis sang about in his canticle, I am now sensing these connections with the world around me on a deep, visceral level. This is what Francis was getting at: cultivating a rapport with this world that is not abstract or merely transactional, but instead experiencing the world viscerally without judgment or denial, without resistance or avoidance, as a brother and a sister with all the familiarity (and tension) implied in a family.

It is an experience that could make us quite vulnerable, which is why much of the time most people run away from this closeness and disregard or trivialize this way of being with judgment. But when the realities of life hit, and you have lost everything, what is left is the stunning beauty of our relationships with one another, with this world, and with our God. This path of interdependence is care-filled, relational, and felt.

This is how we come to understand the real wisdom of Francis and begin to live the canticle.

3 thoughts on “Living ‘The Canticle of the Creatures’ ”

Beautiful article Darleen with meaty spirituality. Perfect for me at this time. Hard to feel a sibling relationship with pain and fear.

Thank you, Darleen, for opening further reflection on and exploration into Francis and his relationships with loss, interdependence with siblings, appreciation of beauty.

These days, I am grateful to be present with my Dad in this final season of his life as he lets go in deeper ways, responding to the experience of loss. It seems he is drawn to greater simplicity, transparency and beauty… into mystery where joy and sorrow embrace. Beautiful!

“But when the realities of life hit, and you have lost everything” – including “the stunning beauty of our relationships with one another, with this world” – what is left is our stunning DEPENDENCY on God. Nothing else matters. Which is why He puts us there.